This my second contribution- just in time!- to the wonderful ReadIndies event which has been running all month, hosted by Karen and Lizzy.

Initially I planned for this post to be two novellas published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, in honour of the event’s origins as Fitzcarraldo Fortnight. However, the second novella I read was so unrelentingly brutal and grubby – though expertly written and translated – that ultimately I couldn’t recommend it that much. So instead this post covers the initial Fitzcarraldo novella which I loved, and the independently published novel I read after the second novella in order to recover!

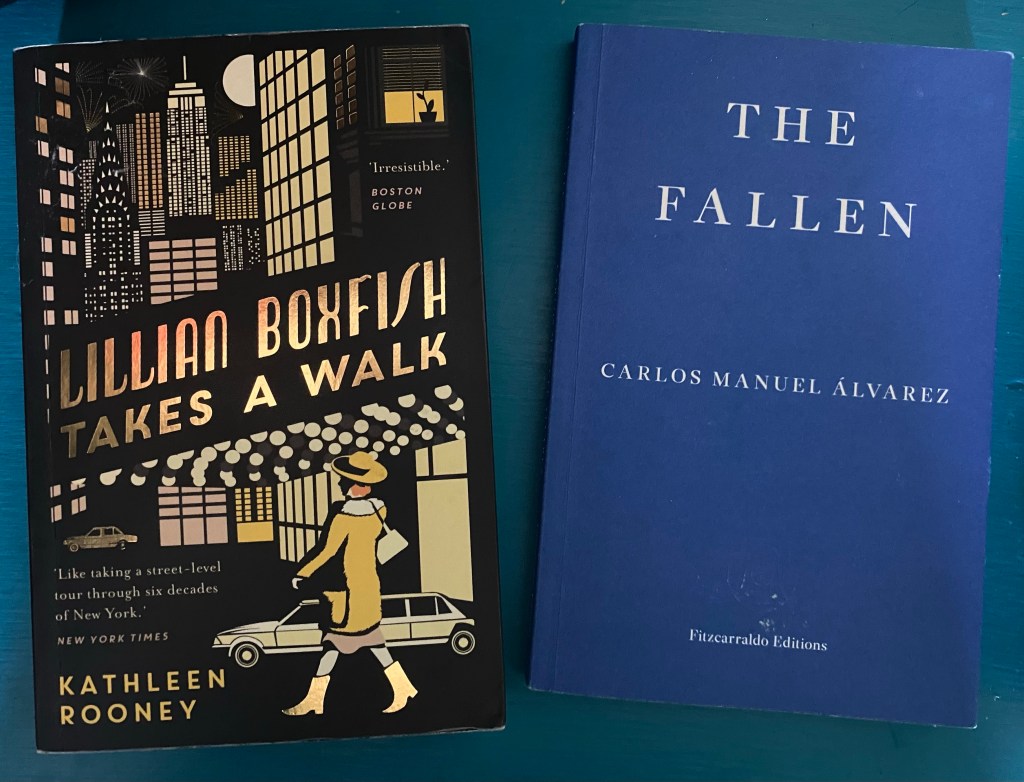

Firstly, The Fallen by Carlos Manuel Álvarez (2018 trans. Frank Wynne 2019) which forms a stop on my Around the Word in 80 Books challenge as it’s set in Cuba. The story follows one family over a short period, each member narrating a chapter at a time.

The mother, Mariana, is experiencing black-outs and fits, attributed to the treatment she had for womb cancer. Her husband Armando is a manager in a state-owned tourist hotel, committed to the communist ideals of the past even as the world moves on around him. His daughter María works with him and helps care for Mariana:

“I didn’t want to contradict her, I simply stood and watched. Just then, she hunched over and the strangest thing happened. Her face drained away, seemed to contract, like when you clench a fist, as though everything was drawing back around her nose. Her eyes fell, her forehead and mouth shrivelled and her cheeks began to wither. Then she burst into tears and collapsed.”

Meanwhile her brother Diego is completing his military service, devoid of any commitment to the cause:

“Armando, indefatigable, continued inoculating me with his positive energy, his moral code, his inexhaustible optimism, injecting me with a radioactive material that, on contact with the real world, simply exploded like acid in a burst battery and was transformed into frustration. I’m eighteen years old but I feel like an old man.”

All the characters are flawed in their different ways but all are recognisably human and sympathetic. I felt most for poor Armando, surrounded by corruption that nobody cared about but him:

“The truth is, they were firing him because he refused to accept others stealing, but since they couldn’t tell him that, they told him they were dismissing him for stealing,”

The contrast between Armando and his children effectively demonstrates the tension between the ideals of the past and the reality of the present. However, this is never done at the expense of characterisation the individual relationships. The tension within a family, vulnerable to disintegration as the health of its matriarch deteriorates, felt very real.

The polyphonic style builds up a picture of a loving family with all it’s frustrations, secrets and things left unsaid. It also demonstrates the differing responses of people to the same situation as we hear the same events given a different meaning by the various characters. This wasn’t at all frustrating as Álvarez managed to sustain an engaging and coherent narrative.

I really loved this novella. I thought the language was beautiful without obscuring the difficulties it was exploring for the family, and the device of using one family to explore wider Cuban society and history didn’t feel at all clunky or contrived.

“The acrid smell that tickled my grandfather’s nostrils still lingers. This is a pueblo fecund with the dry bittersweet dust of horseshit and with the sea a few kilometres away, even if we turn our back on it. The last street in the pueblo, the street that leads to the train station, the street where my grandfather settled, where my father started out in life, where later I started out, is broad but deserted, with much light on the asphalt, with light that trickles down the gutters and lighting the potholes, as though light were contained in a glass and the glass had tipped over. No one comes here.”

Secondly, the delightfully titled Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney (2017) published by Daunt Books. This was a lovely escapist read – just the ticket after the second traumatic novella.

It’s New Year’s Eve in 1984, and the titular heroine is one year older than the century (although no-one knows this as she routinely lies about her age). Having moved to New York City when she started out on her career, she dons her fur coat (yuck) and her flame orange lipstick, to take a circuitous route around the city she loves – just about:

“The city I inhabit now is not the city that I moved to in 1926; It has become a mean-spirited action movie complete with repulsive plot twists and preposterous dialogue.

[…]

I love it here, this big rotten apple. I’m near my old haunts, my Sycamore trees, my trusty RH Macy’s.”

Lillian became an advertising copywriter for the famous store, the highest-paid woman in the industry in the 1930s, pioneering her own particular style:

“Nobody was funnier than I was, not for a long time, not for years. Mine was a voice that no one had heard speaking in advertisement before, and I got them to listen. To listen and then, more importantly, to act on what they’d heard.”

Lillian is based on the real person of Margaret Fishback, and the novel was written with the cooperation of Margaret’s family, with Lillian’s quoted copy actually belonging to Margaret.

Certainly Lillian’s memories of her life in New York seem authentic as she navigates a sexist working world unused to professional women. This may sound reminiscent of Mad Men, but I would say it’s not nearly as dark. It’s not totally light either – we learn Lillian had some very difficult times – but Lillian is resilient and peppy, and her voice rings out.

Like Mad Men though, Lillian Boxfish… brilliantly evokes a time and a place. You gain a wonderful sense of New York in the early decades of the twentieth century, with it’s rapid, optimistic growth, ever skywards.

“It was freshly built when Helen and I moved in, completed in 1926. The street noise then was different than now – everything was being constructed, going up, up, up. Progress is loud: riveters riveting, radios blaring.”

We hear about Lillian’s friends, her marriage to the dashing Max (contrary to all her plans) and raising her son Gian. But most of all we hear about Lillian’s relationship with herself, and it is one that has not always been easy:

“But there was no way to know, and no way to go back. I could not revise. I had been who I had been, and so I largely remained.”

Still, Lillian remains undaunted and in her ninth decade she remains interested in people. She encounters a few on her night-time perambulation, seemingly enjoying chatting about the mundane as much as she does the more dramatic encounters. Her career long behind her, she retains her pithy turn of phrase:

“Salt and pepper hair shellacked into an oceanic sweep above his leonine face. Like so many public television people, he was a former radio guide, with a voice made for broadcasting: even his name sounded like an avuncular chuckle.”

I really enjoyed my time with Lillian. Her voice was distinct, unique and entertaining. She described the love of her life – New York City – with clearsighted affection. A formidable woman, and a likable one.

“I am not going to stay off the street. Not when the street is the only thing that still consistently interests me, aside from maybe my son and my cat. The only place that feels vibrant and lively. Where things collide. Where the future comes from.”

To end, Lillian is haunted by a song she keeps hearing on the streets, a rap that she enjoys. Finally, it is identified for her: