Firstly, in breaking news (in the sense that it’s not news and of zero interest or urgency) I’ve finally joined the cool kids over at twitter so please validate my fragile sense of self and join me @madame_bibi. More importantly, I’ve tried to follow as many of my bloggy friends as possible but if I’ve missed you please let me know & I will rectify the situation forthwith 🙂

On with the post! This is my second contribution to Reading Ireland 2017 aka the Begorrathon, hosted by Cathy at 746 Books and Niall at Raging Fluff. I’m hoping to just get this posted in time, as I was sick for a week and while this meant I could finally watch the entire series of Taboo that I had stacked up, I was incapable of reading the printed word (my capacity for dribbling over Tom Hardy remained unaffected). If I’m too late, I hereby proclaim that there are at least 32 days in March 😉

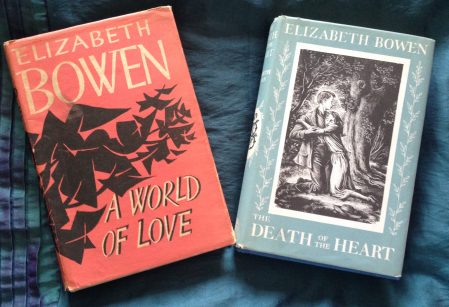

So, its Elizabeth Bowen all round as I look at two of her novels, simply because I was lucky enough to find these lovely hardbacks in my favourite charity bookshop a wee while ago:

Firstly, The Death of the Heart (1938), which I pounced on as soon as I saw it, remembering Jacqui’s wonderful review. Portia, a sixteen year old orphan, moves to London following a transitory life in hotels with her parents, to live with her half-brother and his wife who she barely knows. Wiki quotes Bowen as describing the novel thusly:

“a novel which reflects the time , the pre-war time with its high tension, its increasing anxieties, and this great stress on individualism. People were so conscious of themselves, and of each other, and of their personal relationships because they thought that everything of that time might soon end.”

Certainly the individuals in the novel are self-conscious, but they’re not really aware of one another. Poor Portia finds herself part of a society of selfish individuals who don’t know what they want and so end up tormenting each other while they try and work it out. Portia’s step-mother Anna is unhappy, as is her brother, but neither are sure it is the marriage to one another that is making them miserable. A rejected lover of Anna’s, Eddie, seduces Portia to alleviate his boredom, not realising that to do so to a naïve and loving 16 year old is cruel and damaging. There is an all-round lack of intimacy:

“But something that should have been going on had not gone on: something had not happened. They had sat round a painted, not a burning, fire, at which you tried in vain to warm your hands.”

Portia is temporarily packed off to the seaside to stay with a family that the London set look down as being a bit common, but they are at least lively:

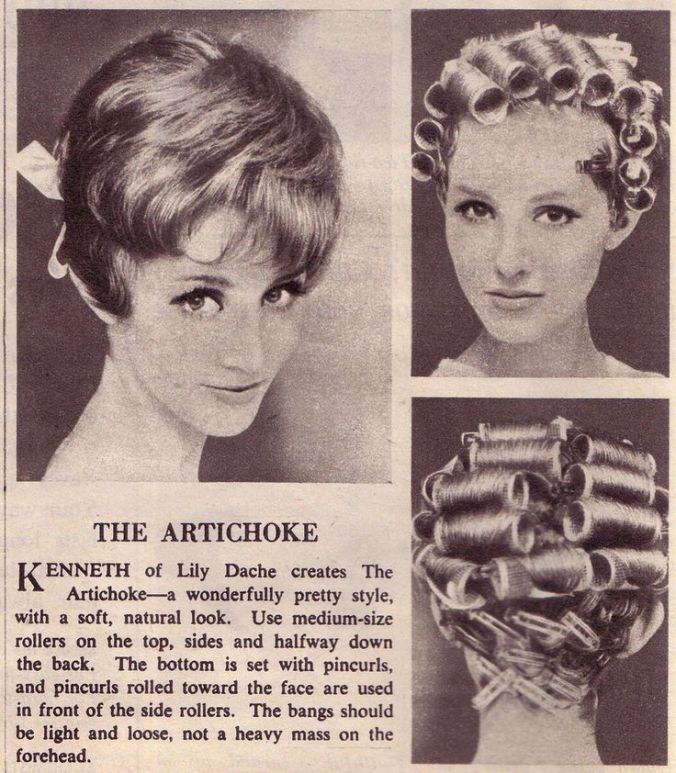

“Mrs Heccomb took off her hat for tea and Portia saw that her hair, like part of an artichoke, seemed to have an upgrowing tendency…This, for some reason, added to Mrs Heccomb’s expression of surprise.”

However, while the Heccombs see Eddie for the cad and bounder he is, they are neither able to convey this adequately to Portia, nor is she willing to listen. What emerges as Portia tries to find her place in the world and warm relationships within it, is how deeply inadequate human beings can be at communicating with one another. Bowen is interested in the fantasies that are constructed in lieu of real understanding and how these can be sustaining but ultimately empty.

“Not for nothing do we invest so much of ourselves in other people’s lives – or even in momentary pictures of people we do not know. It cuts both ways: the happy group inside the lighted window, the figure in the long grass in the orchard seen from the train stay and support us in our dark hours.”

The novel lacks any sentimentality and is a sharply observed portrait of interwar society. What stops it from being depressing is Bowen’s glorious prose, her dry sense of humour (I don’t think we are supposed to take the characters as seriously as they take themselves) and the sense that love – imperfect and in many different guises – is there to be found, sometimes in the oddest of places.

Apparently hair like an artichoke was an actual thing, although I think Bowen had something more flamboyant in mind…

Image from here

Secondly, A World of Love (1955), which I thought absolutely stunning. Bowen has matured between these two novels and is telling less, showing more, to once again explore the complexities of human relationships with great subtlety. Lilia owns Montefort, a country house in County Cork, and her dead cousin Guy’s fiancé Antonia, lives there with her husband Fred, an illegitimate member of the family, who runs the estate so they live rent-free.

“Of this arrangement it had not yet been decided whether it worked or did not work, still less if it equitable or, if not so, at whose expense.”

Over the course of a few claustrophobically hot days in summer, Antonia and Fred’s daughter, Jane, finds love letters written by Guy to an unnamed woman which is assumed to be Antonia. This will act as a catalyst to bring the unspoken tensions between the adults into sharp relief:

“Almost no experience, other than Guy and their own dissonance, could they be said to have had in common; and yet it was what they had had in common which riveted them. For worse or better, they were in each other’s hands. Such a relationship is lifelong.”

Meanwhile, Jane is on the edge of burgeoning adulthood:

“Not a straw stirred, or was there to stir, in the kennel; and above her something other than clouds was missing from the uninhabited sky. Nothing was to be known. One was on the verge, however, possibly, of more.”

I really adored this novel. Again, it was sharply observed, psychologically astute, and with a wonderful undercurrent of dry humour. Bowen minutely dissects human relationships and exposes all their contradictions and conflict, but also how compromise and understanding can be reached. A World of Love felt tighter than The Death of the Heart, the containment of a few days in pretty much one place effectively conveying the claustrophobia that exists for the characters in their various ways, even as they roam a huge estate. Yet Bowen is almost baroque at times, her descriptions rich and layered and filled with meaning:

“No part of the night was not breathless breathing, no part of the quickened stillness not running feet. A call or calling, now nearby, now from behind the skyline, was unlocatable as a corncrakes in the uncut grass. Arising this was, on the part of the two who like hundreds, seemed to be teeming over the land, carrying all before them. The night, ridden by pure excitement, was seized by hope. .. All they had ever touched still now physically held its charge – everything that had been stepped on, scaled up, crept under, brushed against or leaped from now gave out, touched by so much as air, a tingling continuous sweet shock, which the air suffered as though it were half laughing, as was Antonia.”

I realise I may have lost some of you there. But if you don’t mind that sort of prose at times, especially when it’s surrounded by an astute unblinking eye for human foibles and a compassion for our frailties, please do given Bowen a try!

So that’s the end of a very hurriedly written post, please excuse all typos and general incoherence! Now to end with an Irish musician and a blatant grovel to my mother (as he is one of her favourites and I failed on Mother’s Day last weekend):