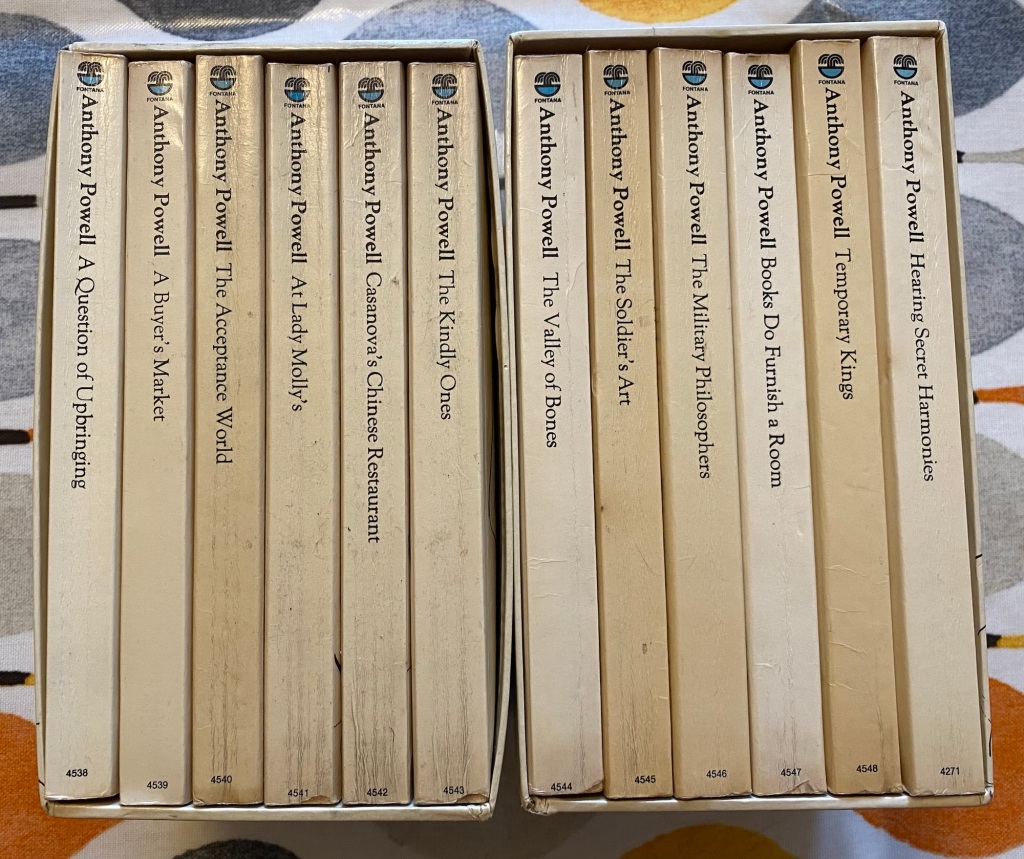

It’s month three in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

Either I’m getting used to Powell’s syntax, or as he developed as a writer he found a fondness for full stops, because I found The Acceptance World (1955) had a much more comprehensible prose style than its two predecessors.

As usual Powell doesn’t explicitly state when the story is set, but a reference early on to “the country’s abandonment of the Gold Standard at about this time” means it starts around 1931. Economics feature heavily in The Acceptance World and the privileged circles Nick moves in are not entirely immune. There are frequent references to “the slump” taking a toll. Unfortunately political satire never seems to date;

“’Intelligence isn’t everything,’ I said, trying to pass the matter off lightly. ‘Look at the people in the Cabinet.’”

Schoolfriends and university friends reappear: Templer, Widmerpool, Stringham and Manners. The title is taken from recurring talisman/character Widmerpool’s new job. Templer tells Nick “’Widmerpool is joining the Acceptance World. […] he is going to become a bill-broker.’” This work, like most City work, makes absolutely no logical sense and reaps large financial rewards. Essentially Widmerpool accepts the transitory debts of companies and takes them on based on their reputation. Later in the novel Nick sees this principal applying more widely:

“The Acceptance World was the world in which the essential element – happiness, for example – is drawn, as it were, from an engagement to meet a bill. Sometimes the goods are delivered, even a small profit made; sometimes the goods are not delivered, and disaster follows; sometimes the goods are delivered, but the value of the currency is changed. Besides in another sense, the whole world is the Acceptance World as one approaches thirty; at least some illusions are discarded. The mere fact of still existing as a human being proved that.”

The tone felt more sombre in this volume. Having spent time with Nick through his schooldays and at debutante parties in the first two volumes, he is now nearing thirty. Europe’s economic and political situation, while not given lengthy consideration, is creeping into everyday life. On a smaller scale, there are divorces, disillusionment and alcoholism amongst his peer group. If this sounds too depressing, Powell’s satire keeps a sharp, humorous eye on proceedings, such as Stringham’s divorce:

“Soon after the decree had been made absolute, Peggy married a cousin, rather older than herself, and went to live in Yorkshire, where her husband possessed a large house, noted in books of authentically recorded ghost stories for being rather badly haunted.”

He also sets a humorous tone from the beginning, detailing a meeting with his Uncle Giles in an unprepossessing Bayswater hotel:

“He spoke slowly, as if, after much thought, he had chosen me from an immense number of other nephews to show her at least one good example of what he was forced to endure in the way of relatives.”

The ‘her’ in quote above is Mrs Erdleigh, a dreamy woman who reads cards: “She seemed hardly to take in these trivialities, though she smiled all the while, quietly, almost rapturously, rather as if she were enjoying a warm bath after a trying day shopping.”

The novel expands on Nick’s circumstances of work a bit further, although it remains all a bit vague. He has published a novel but he says very little about it:

“‘I liked your first,’ said Quiggin.

He conveyed by these words a note of warning that, in spite of his modified approval, things must not go too far where books were concerned.”

There is also consideration of women, as Nick begins an affair with an old friend. His observations are callow generalisations, but I don’t think the reader is supposed to find Nick particularly insightful or wise in this regard. In contrast, his observations about men are astute, from the comic summation:

“Like most men of his temperament, he held, on the whole, rather strict views regarding other people’s morals. […] In any case he was not greatly interested in such things unless himself involved.”

To a thoughtful consideration of those slightly older than him affected by the previous war:

“He seemed still young, a person like oneself; and yet at the same time his appearance and manner proclaimed that he had had time to live at least a few years of his grown-up life before the outbreak of war in 1914. Once I had thought of those who had known the epoch of my own childhood as ‘older people’. Then I found there existed people like Umfraville who seemed somehow to span the gap. They partook of both eras, specially forming the tone of the post war years; much more so, indeed, than the younger people. Most of them, like Umfraville, were melancholy; perhaps from the strain of living simultaneously in two different historical periods.”

I really enjoyed The Acceptance World and there’s so much I haven’t covered here. I’m starting to find returning to the sequence like sinking into a big squashy chair. Although it’s not a comfort read, Powell’s writing, his comedy and insights, and the (now) familiar world he creates are a joy to return to.

I’m also beginning to really understand the complexity and subtlety of what Powell is doing in A Dance to the Music of Time. His style is so deceptive; he seems to be writing about nothing while in fact he’s writing about everything:

“I began to brood on the complexity of writing a novel about English life, a subject difficult enough to handle with authenticity even of a crudely naturalistic sort, even more to convey the inner truth of the things observed.”

To end, in honour of Mrs Erdleigh: