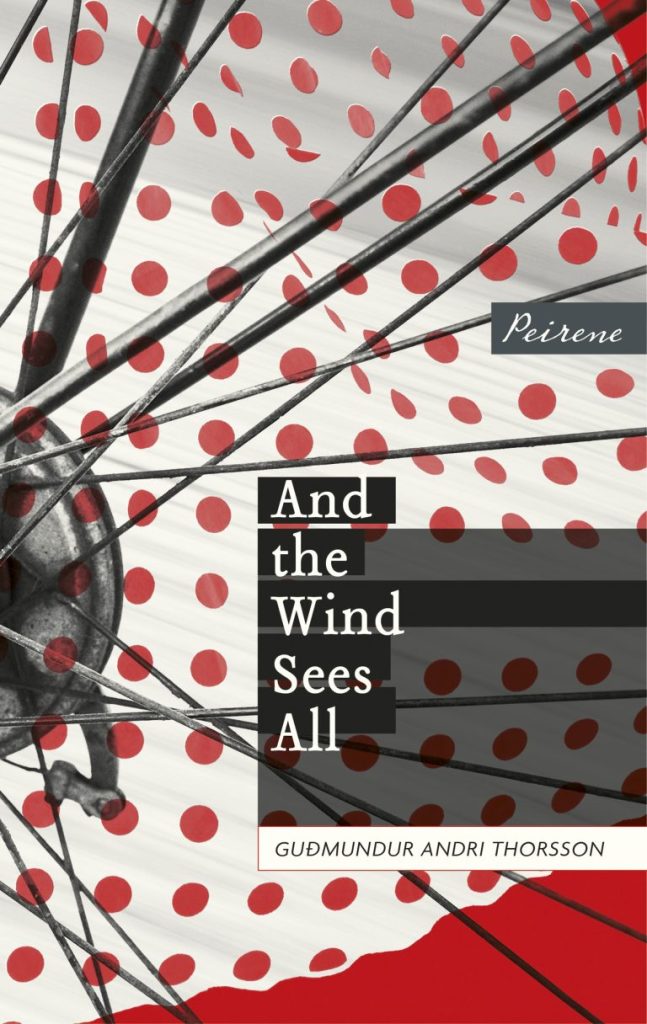

My final novella of May is And the Wind Sees All by Guðmundur Andri Thorsson (2011, transl. Björg Árnadóttir and Andrew Cauthery 2018), published by the ever-reliable Peirene Press.

The entire novel takes place within two minutes: the time it takes Kata, conductor of the village choir, to cycle down the main street of Valeryi in her polka dot dress.

“Everything is singing in the bright light. The sun sings, the sea, fish, telegraph poles, cows, flies, horses, dogs, the old red bicycle Kalli and Sidda gave her. She feels the day will come when her brown hair will once again have its red lustre. Once again her eyes will sparkle. Once again she’ll sing inside herself as she plays the clarinet. Once again there will be life in her existence. Once again she will be loved.”

We don’t find out why Kata has lost her sparkle until towards the end of the novella. In the meantime, as the residents of the northern Icelandic village see her go by, we get glimpses of their lives and a picture of the community.

The chapters are told from different people’s viewpoints but characters recur – as they would in such a small community – along with images and themes, weaving the fragmentary experiences into a whole.

One of the most harrowing stories belongs to Svenni, and yet his chapter begins quite lightly:

“Svenni lives in one of those houses that look like a man with his trousers hitched up far too high – a little house on big foundations.”

We learn that reticent “good bloke” Svenni, a surprise participant in the choir, has traumatic reasons for keeping himself to himself.

There are lighter moments too, such as Lalli the Puffin being so-called because he owns the Puffin restaurant, but also because “he struts and darts his eyes around like an inquisitive puffin. The villagers are all familiar with his distinctive waddle and smile to themselves when they see him.”

And there are moments in between, like the fragile reunion of two middle-aged people who had been teenage lovers back when they “presented their pain to each other” and are now taking a walk.

The coastal Icelandic setting of the fictional village is beautifully evoked throughout:

“The village is not just the movement of the surf and a life of work, the clattering of a motorboat, or dogs that lie in the sun with their heads on their paws. It’s not only the smell of the sea, oil, guano, life and death, the fish and the funny house names. It’s also a chronicle that moves softly through the streets, preserving in elemental image of the village created piece by piece over the course of centuries.”

The back of my copy refers to “relaxing Nordic hygge in a novel” – I disagree. And the Wind Sees All is not a harrowing novel but it’s not escapist either. There are villagers with traumatic pasts, there is self-medicating with alcohol, there is addiction and heartbreak. There’s also love and friendship. Thorsson shows how these experiences sit amongst a beautiful village, where the community is coming together for a choir concert. It all exists simultaneously, within the two minutes of Kata’s bike ride.