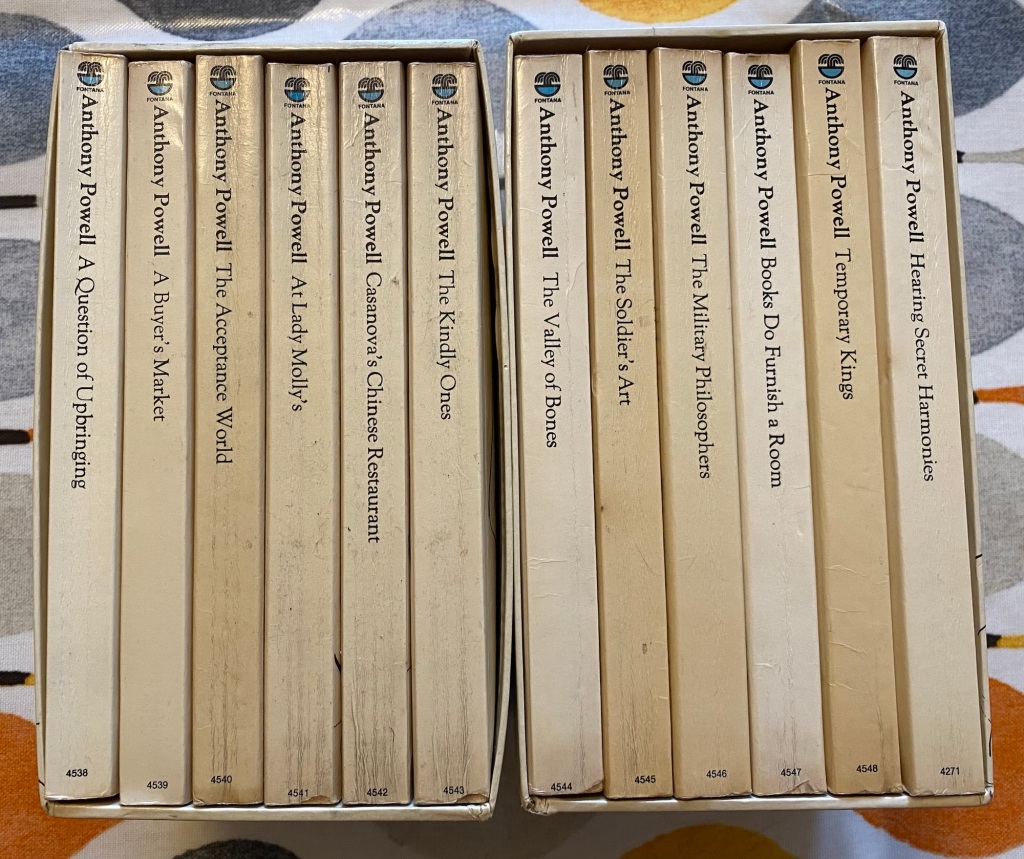

This is the ninth instalment in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

The ninth volume, The Military Philosophers, was published in 1968 and is set in the latter part of World War Two. It forms the final part of the war trilogy within the sequence, after The Valley of Bones and The Soldier’s Art.

Nick is working in Whitehall as a military liaison during the later stages of the war, and Powell captures the quirks and foibles of his colleagues in these powerful – for some – administrative roles. He demonstrates how soldiers are still people with all their flaws; and how everyday concerns run alongside such enormous ones as the fate of nations and the likelihood of imminent death.

During an air raid, Nick reflects:

“Rather from lethargy than an indifference to danger, I used in general to remain in my flat during raids, feeling that one’s nerve, certainly less steady than at an earlier stage of the war, was unlikely to be improved by exchanging conversational banalities with neighbours equally on edge.”

While I don’t suppose Powell was anti-war or anti-establishment, he brings his clear sight to all he portrays, including the venerated men of war. An imposing portrait of the man who came to personify the previous war is described:

“Kitchener’s cold and angry eyes, haunting and haunted, surveying with the deepest disapproval all who came that way.”

And in a rare instance of Powell describing a real-life character (though never named), Field-Marshall Montgomery is all too believably portrayed:

“An immense, wiry, calculated, insistent hardness […] one felt that a great deal of time and trouble, even intellectual effort of its own sort, had gone into producing this final result. The eyes were deep set and icy cold.”

There’s absolutely no jingoism in The Military Philosophers. Nick is a loyal soldier, but he doesn’t automatically equate the behaviour of his country with honourable deeds:

“The episode strongly suggested that the British, when it suited them, could carry disregard of all convention to inordinate length; indulge in what might be described as forms of military bohemianism of the most raffish sort.”

Truly terrifying is the development of Widmerpool in this volume. Already a deeply unnerving character, Powell has him arrive in the volume with some levity:

“‘You must excuse me,’ he said. ‘I was kept by the Minister. He absolutely refused to let me go.’

Grinning at them all through his thick lenses, his tone suggested the Minister’s insistence had bordered on sexual importunity.”

Later we are reminded of Widmerpool’s absolute lack of any morality, when he describes the Kattyn Forest Massacre as merely “regrettable”.

By the end, he is truly sinister, observing “I have come to the conclusion that I enjoy power.” He informs Nick that he will revel in the command of empire overseas. The racism is explicitly stated; the violence of imperialism implied.

Various associates from Nick’s past reappear in his life. We learn that Nick’s childhood friends Stringham and Templar are both most likely dead, and sadly so is my favourite character General Conyers, succumbing to a heart attack after chasing looters and trying to stop the theft of a refrigerator.

Stringham’s niece, Pamela Flitton, plays a significant role in this volume, essentially by sleeping with a lot of different men and being furious the whole time. Let’s just say her taste in partners leaves a lot to be desired…

There are lighter moments too, and I particularly enjoyed Nick’s colleague Finn risking both a court martial and being stripped of his VC, in his desperation to collect a fresh salmon and using a military car to do so.

The volume ends with the Victory Service at St Paul’s, and then Nick going to collect some civilian clothes at Olympia. It is a subdued ending, deliberately so.

“Everyone was by now so tired. The country, there could be no doubt, was absolutely worn out.”

I found the tone very moving, reflective of all the loss that had been experienced through the war years and all that must now be endured in the immediate post-war period.

“The London streets by this time were, in any case, far from cheerful: windows broken: paint peeling: jagged, ruined brickwork enclosing the shells of roofless houses. Acres of desolated buildings, the burnt and battered City lay about St Paul’s on all sides.”