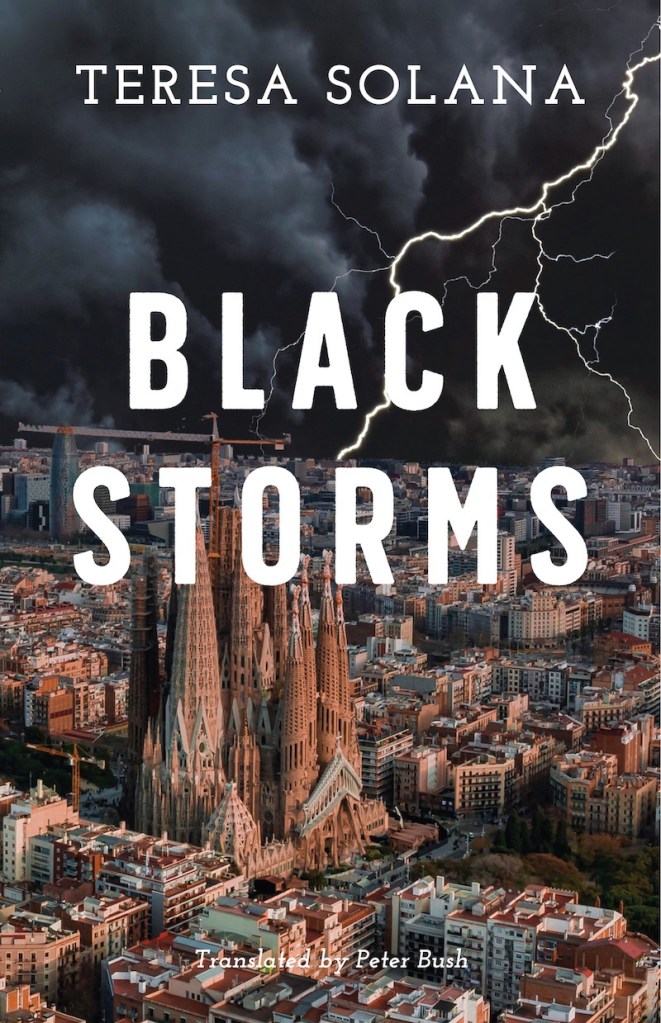

Today I’m taking part in a blog tour for Corylus Books, a lovely indie publisher with a focus on translated crime fiction. For those of us in the northern hemisphere the nights are drawing in, and settling down with a crime novel that opens on All Saints Eve (Hallowe’en) felt like a perfect read for this time of year.

Here is the blurb from Corylus Books:

“Who murders an elderly professor in his university office – and why? Norma Forester of the Barcelona police force is handed the case and word from the top is to resolve it as quickly and as quietly as she can. Set against the backdrop of one of the most vibrant and exciting cities in Europe, Black Storms also highlights the darker side of Barcelona and its past, overshadowed by the bitter Civil War of the 1930s.

The past also touches Norma Forester, the granddaughter of an English International Brigades volunteer who didn’t survive to see his Spanish daughter.

This first novel in Teresa Solana’s is a fast-paced crime story that balances the hunt for a killer with Norma Forester’s colourful and complex personal life. She’s surrounded by her forensic pathologist husband, her hippy mother, and her anarchist squatter daughter whose father is Norma’s husband’s gay brother. Then there are Norma’s police colleagues and superiors – plus an occasional lover she can’t resist meeting.”

Black Storms begins with the murder from the point of view of the murderer. This wasn’t gory or gratuitous. There had also been a brief but effective portrayal of the victim, Professor Francesc Paradella who was an expert on the Spanish Civil War, which definitely evoked my sympathy without being sentimental.

We’re then taken to a birthday dinner at Deputy Inspector Norma Forester’s family home. I really enjoyed the portrait of Norma’s family, full of somewhat eccentric characters without seeming unrealistically colourful.

Her mother Mimí looks like “an old Hollywood actress who’d gone to seed or an eccentric fortune teller.”, in contrast to Isabel, her conservative mother-in-law. Her daughter Violeta briefly returns from living in a squat and also visiting is Aunt Margarida, Mimí’s step-cousin and a nun aka my favourite character:

“she’d been living comfortably isolated from the world and its problems for eight years, reciting ancient prayers behind those impenetrable stone walls. However, occasionally, she did miss the freedom of her secular life and, now and then, invented an excuse to go out and took advantage of her escape to go to bingo sessions, drink cocktails in Boades and hit the town with Mimí.”

I also liked Norma’s husband, principled forensic examiner Octavi, angry that because the Professor was from a powerful family, his death is treated more seriously than others.

“There were class differences even among the dead: upper-class corpses that led to frantic investigations and second-class corpses that were processed routinely.”

The legacy of the Civil War is part of Norma and Octavi’s home, not only through the family history but in their present. Senta, Norma’s grandmother mistakes outside noises for those of conflict and becomes highly distressed. It’s a brief scene but so moving in how it demonstrates the enduring trauma of war.

The reader soon knows who the murder is, someone pathetic and seedy, and very believable. The mystery of Black Storms is not therefore whodunit, but why. The why enables Solana to look at the long shadows cast by the Spanish Civil War and the enduring corruption in society.

My knowledge of the Spanish Civil War is shockingly rudimentary and Solana did a great job of weaving the history throughout the story without ever info-dumping. Past events are evoked through characters; there is an excellent scene between Norma, whose grandfather was killed by state execution, and Gabriel, her second-in-command, whose grandfather was killed by FAI anarchists.

The most severe condemnation is saved for how the legacy has been mishandled: “the circus orchestrated in the corridors of power had succeeded in drowning the transition in a mist of amnesia”.

But the novel is also resolutely contemporary and Barcelona is wonderfully evoked, even the less salubrious sides: “A city for tourists with cirrhotic livers looking for cheap alcohol.” Ouch!

From the start Black Storms had an assured style and Solana is so accomplished in how she weaves together a crime plot, the legacy of the Spanish Civil War, and contemporary social commentary. It never felt remotely laboured and the story pace was never weighed down by the importance of the issues highlighted. I thought Black Storms was a hugely impressive novel. And now I want another in the series to be translated, because I am already missing Aunt Margarida!

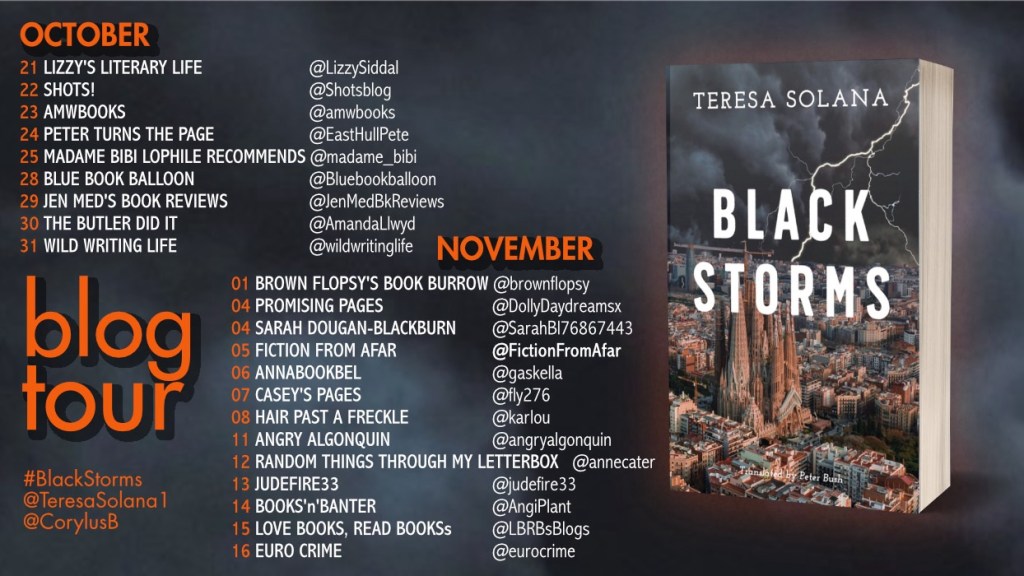

Here are the stops from the rest of the tour, so do check out how other bloggers got on with Black Storms: