Trigger warning: mentions suicide

This is my second contribution to this week’s 1954 Club, hosted by Simon and Kaggsy, and a chance to revisit Barbara Comyns, having really enjoyed Our Spoons Came From Woolworths.

The opening line of Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead may have usurped The Crow Road* to become my favourite beginning to a novel ever:

“The ducks swam through the drawing-room windows.”

Thus the scene is set for an unsettling domestic tale where nothing can be taken for granted.

The Willoweed family live in an English village where the river has just flooded in June. Then follows pages of dead animals, which I was prepared for, having read Jacqui’s wonderful review but I was exceedingly relieved when it ended (unfortunately there was also a horrible cat death later). Much as I could have done without the litany of death, it sets the tone for the darkness that follows.

In 1911 Emma, Dennis and Hattie live with their father Ebin and their grandmother who rules with a rod of iron. She is permanently furious, which Ebin attributes as follows:

“It’s all this cleaning, I suppose; but she can’t expect me to help; my hands are my best feature, and they would be ruined.”

Ebin does very little apart from make vague overtures towards his children’s schooling and sleep with the baker’s wife.

“‘Father makes me hate men,’ thought Emma as she pumped water into a bucket.”

This is not an idyllic pre-war rose-tinted existence. Money is tight, relationships are tense, there is sexual deceit, violent undercurrents that threaten to overwhelm, and macabre power games. Grandmother Willoweed treats the servants horribly, but Old Ives the handyman is a match for her:

“They always exchanged birthday gifts, and each was determined to outlive the other.”

Their lives are disrupted by a mysterious illness that sweeps through the village. People kill themselves following horrific delusions. By the time the cause of the illness has been identified, tragedy has touched the family and violence has ensued. As the title tells us, lives will have changed irrevocably one way or another.

I don’t want to say much more as the joy of reading Barbara Comyns is being so unsettled as to have no idea which way she is going to take you. There’s no-one like her; her view is so singular, so disturbing and yet so compelling. I found Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead brutal and horrifying, and also funny and enchanting. I couldn’t look away.

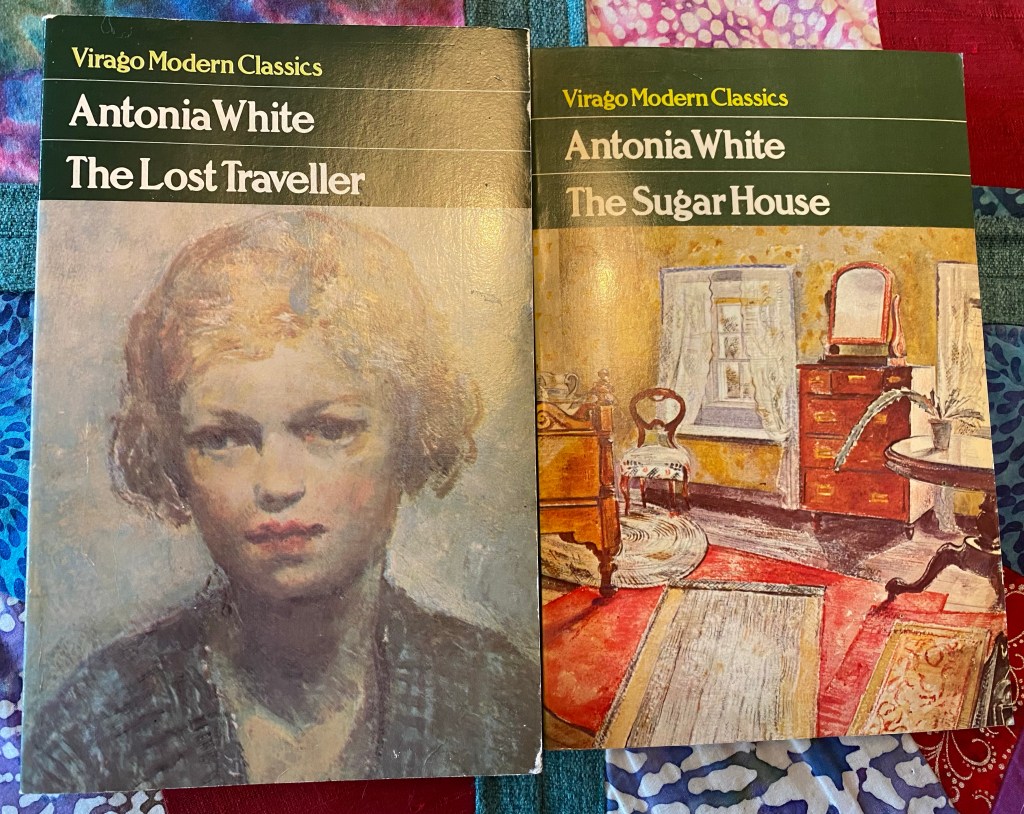

Secondly, I wrote last week about the middle two novels in Antonia White’s quartet, detailing the early life of Clara Batchelor, and now the final instalment, Beyond the Glass.

The novel picks up precisely where The Sugar House left off, with Clara and Archie having decided to separate. Clara moves back to her parents’ house to live with them and her grandmother in West Kensington. As she packs up her old life, she feels disassociated:

“She had the odd impression that it was not she who was stripping hangers and throwing armfuls of clothes into suitcases but some callous, efficient stranger. She herself was lying on the unmade bed, staring blankly at the cracks in the sugar-pink ceiling.”

This sense of disassociation deepens and broadens throughout the novel. When Clara announces to her mother “It’s a great relief not to have any feelings. I’m certainly not going to risk getting involved with anyone again.”

The reader of course knows what will happen. She attends a party with her friend Clive Heron (an intriguing character, my personal theory is he works for MI5) and falls instantly in love with the dashing soldier Richard Crayshaw.

What follows is such a clever exploration of someone slowly – then suddenly – unravelling. Clara stops eating and sleeping, she has a “strange sense of heightened perception” ever since she danced with Richard. She believes they communicate telepathically, a belief supported by others, but then she thinks the photographs of dead soldiers in her father’s study are speaking to her. She has gone from no feeling:

“Null and void. Null and void. She sat staring at the roses on her bedroom wall-paper, saying the words over and over again until she was half hypnotised.”

To too much feeling. At first her mania is disguised by being in love – plenty of people feel heightened and have reduced appetite and problems sleeping in the excitement of new romance. Certainly that is what Clara’s mother Isabel believes.

But gradually the reader begins to realise that Clara is really quite unwell. As Beyond the Glass is told from Clara’s perspective this takes some time, but it dawns us through others’ responses to her. In this way it is reminiscent of Wish Her Safe at Home, another excellent novel about severe mental illness.

Eventually she is ‘certified’ – made an in-patient at a public mental health hospital. The descriptions of the environment and the practices make me wonder how on earth anyone would have a hope of ever becoming well again. Thankfully mental health services, though chronically underfunded, are very different now.

I was so impressed with how White conveyed Clara’s disorientation and confusion, without making the narrative confusing and disorienting at all:

“Time behaved in the most extraordinary way. Sometimes it went at tremendous pace, as when she saw the leaves of the creeper unfurl before her eyes like a slow motion film, or the nurses, instead of walking along the passage, sped by as fast as cars. Yet often, it seemed to take her several hours to lift a spoon from her plate to her mouth.”

During her deep distress there are also echoes of events that occurred earlier in the narrative, particularly in The Sugar House, showing with the lightest of touches that her severe ill health has been building for a while:

“Since her marriage she had had an increasing sense of unreality, as if her existence had been broken off like the reel of a film.”

The recurring images of mirrors and glass as barriers reminded me of Plath’s The Bell Jar. Like The Bell Jar, this novel is based on the personal experiences of the author.

“She had an instantaneous vision of herself as someone forever outside, forever looking through glass at the bright human world which had no place for her and where the mere sight of her produced terror.”

Beyond the Glass ends on a note of hope, and faith, drawing on the Catholic thread that runs through all four novels. At times Clara’s Catholicism is more strongly felt in the story than at others, reflecting the character’s experience of her faith. I’m not religious but I felt the focus on this theme ended the novel and the series perfectly.

It’s so impressive that all the novels in the quartet are distinct and stand individually, while also developing across the sequence a fully realised portrait of Clara, and her family.

I’ve really enjoyed immersing myself in Clara’s life and I’m going to miss her (and her much-maligned mother, a great piece of characterisation). I wish Antonia White had continued writing her story.

“Something told her that, when they saw her again, they would know as well as she did that she no longer belonged to the world beyond the glass.”

To end, I finished my previous 1954 Club post with a filmed musical, so here’s another. The film of The Pajama Game is from 1957 but the Broadway show first appeared in 1954:

* “It was the day my grandmother exploded.”