This is the first of what I’m hoping will be two posts for Margaret Atwood Reading Month 2024 (#MARM2024) hosted by Marcie at Buried in Print, as I aim to read the two short story collections I have in the TBR.

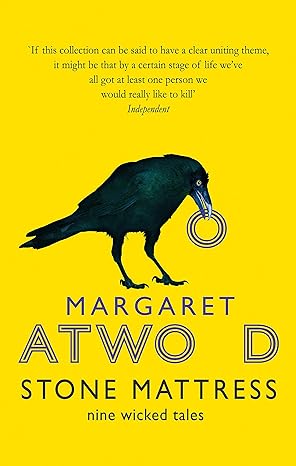

Stone Mattress: Nine Wicked Tales (2014) turned out to be perfect autumn reading with its edge of darkness, verging on Gothic at times.

The first three tales are connected. Alphinland sees fantasy writer Constance negotiate heavy snow after the death of her husband; in Revenant, the poet she loved in her youth, Gavin, tries to manage the frustrations and isolations of older age; in Dark Lady one of his lovers with whom he cheated on Constance is back living with her twin brother.

All of these are grounded in reality, but Atwood weaves through touches of unreality to destabilise any certainty the reader has about what is being portrayed. Constance’s fantasy world is entirely real to her, and there are hints that it is an effective means of controlling people. But is this psychological or metaphysical?

“How did he manage to work his way out of the metaphor she’s kept him bottled up in for all these years?”

Atwood’s portrayal of Constance and Gavin allows for some light satire as to the vagaries of literary trends, and the uses writers make of their art. Gavin enjoyed the male privilege of 1960s bohemianism and is disappointed that the world has moved on alongside his aging body:

“His regret is that he isn’t a lecherous old man, but he wishes he were. He wishes he still could be. How to describe the deliciousness of ice cream when you can no longer taste it?”

Dark Lady portrays the life of an aging muse, using the Shakespeare reference to make Jorrie a slightly ghoulish presence. As her brother Tin reflects on her appearance:

“at least he’s been able to stop her from dyeing [her hair] jet black: way too Undead with her present day skin tone, which is lacking in glow despite the tan-coloured foundation and the sparkly bronze mineral-elements powder she so assiduously applies, the poor deluded wretch.”

“He has to keep reminding her not to halt the sparkly bronze procedure halfway down her neck: otherwise her head will look sewed on.”

Gavin’s nostalgia for the sexual politics of the 1960s is given further short shrift in the titular tale. I was delighted to learn that the idea came about on an Artic cruise, where Atwood’s late husband started to work out how to murder someone on a ship and get away with it. Atwood decided to finish the tale and the logistical details are closely observed.

All the tales are memorable, and the collection finishes on one that feels truly terrifying as an external threat builds towards vulnerable people in a nursing home. Like the tales that have preceded it, Torching the Dusties is touched with the fantastical while staying rooted in the recognisable. Wilma has Charles Bonnet syndrome, hallucinating due to her failing eyesight:

“she locates the phone in her peripheral vision, ignores the ten or twelve little people who are skating on the kitchen counter in long fur-bordered velvet cloaks and silver muffs, and picks it up.”

Atwood relentlessly builds the tension in the tale, ending it on a jovial note that is brilliantly inappropriate.

There’s so much here for Atwood fans to enjoy: the sharp observations (particularly on ageing), the wry societal commentary; the mischievous humour, and of course the fierce intellect. She’s clearly having fun here and encouraging her readers to have fun too. I’m looking forward to the other collection I have to read, Old Babes in the Wood (2023).