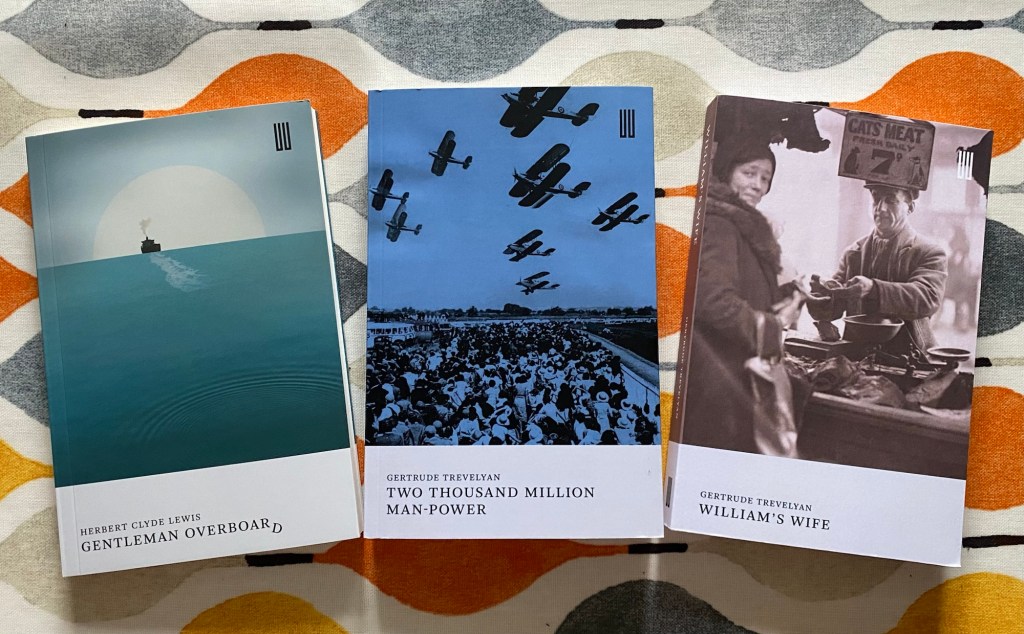

For the final week of Kaggsy and Lizzy’s brilliant #ReadIndies event, I’m focusing on three books from Boiler House Press. Specifically their Recovered Books series edited by Brad Bigelow, founder of www.neglectedbooks.com, which brings “forgotten and often difficult to find books back into print for a new generation to enjoy.”

My second read from the series is Two-Thousand Million Man-Power by Gertrude Trevelyan (1937). The title is the only part of this novel that feels cumbersome; Trevelyan writes with fluency and deftness that is so readable.

She follows Katherine and Robert from 1919 to 1936, from their meeting as young idealists through the strains of their marriage and the economic pressures exerted by forces beyond their control.

They belong to “The half-generation between the war and the post war. They had been brought up in one world and jerked out into another” and the novel explores this notion of them being somewhat lost, even from each other. They both struggle to know what to cling to in a time of rapid change.

When they meet, Robert is working as a cosmetic scientist during the day, and on his own formula for the nature of time from his dingy lodgings in the evening:

“He ate quickly, with appetite, undiscriminating. Turning his back on the meal he lit the gas over a small table near the window and felt in his pocket for the scrap of paper with the dotted figures. As the gas came up, the roofs outside the window turned dark grey. The drawer of the table stuck, half open. He banged it back and wrenched at it and found a wad of notes and pulled in his chair. The roofs outside turn black against the sky and then the sky blacked out.”

Katherine believes in lots of things that need capital letters:

“Katherine believed in progress. She believed in the League of Nations and International Goodwill, in Gilbert Murray and Lord Robert Cecil and H.A.L. Fisher, and in the wonders of Science.”

And so she gifts Robert these capital letters, deciding he is “Working Something Out.”

But gradually the societal forces they both wish to resist make themselves felt. They decide to marry, despite Katherine’s disdain:

“She had, besides, a contempt for married women – content with homes and babies and indifferent to the things that mattered: happy, she thought with a slight sneer, in an emotional and humiliating bondage – which made her, illogically, despise even their efforts to escape.”

She is monumentally judgemental of people. Katherine is an intellectual snob, but her love of ideas doesn’t involve any examining of her own life. This means she can stay secure in her absolute belief that she is somehow better and different to those she looks down on, despite appearing remarkably similar to them externally:

“‘We didn’t marry for bourgeois conventional reasons. Our marriage isn’t bourgeois. We married because we wanted to, that’s quite different, not because we were afraid.’”

Katherine loses her teaching job because married women weren’t allowed to continue in posts. Robert then loses his job due to the world economic crisis. This puts immense strain on them both. Katherine takes a private teaching job she despises; Robert very nearly breaks down entirely.

Throughout, Trevelyan weaves in summaries of world events before returning to the tight focus on Robert and Katherine. I’m not entirely sure how she managed it, but somehow this never felt gimmicky or jarring.

“Agricultural machines in France were grading and marking eggs at the rate of a hundred and twenty a minute. Escalators were speeding up, the biggest building in the Empire was in course of construction at Olympia, Katherine and Robert were in their white-enamelled kitchen one Sunday afternoon, washing the tea things in instantaneous hot water and hanging them to dry in an electrically heated rack.”

The fault lines in Robert and Katherine’s marriage, exposed by the economic strain, only widen. Hilariously, Katherine believes herself to be a communist, when she is in fact a relentless materialist. Trevelyan doesn’t judge her too harshly for this:

“She wanted security and comfort and a Life Worth Living. She wanted Robert to get a sound, decent, progressive job.”

Nothing wrong with any of that, except it does also involve Katherine thinking the world owes them some sort of moral obligation – that they “ought to have” things, and sustaining a consumerism that she entirely fails to see as such. Unable to see how her ideals of progress and modernity have become warped, she continues to position herself as intellectually and morally superior, when really it is only tastes in furnishings that separate her from those she is so condescending towards.

Robert meanwhile finds a way to survive in his work while his big idea amounts to very little, as the reader always knew it would. He has insight but no energy, Katherine the opposite. Two-Thousand Million Man-Power isn’t depressing, but I did find it sad. Ultimately Robert and Katherine seemed so isolated and stymied in very different ways.

I came away from this perceptive, clever and compassionate novel keen to read more by Trevelyan, so I was pleased I’d also ordered William’s Wife (1938). Of which more tomorrow!