This is my contribution to Jean Rhys Reading Week, hosted by Jacqui at JacquiWine’s Journal and Eric at Lonesome Reader. Do check out their blogs and join in!

Firstly, After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1930).

My edition is this 1970s Penguin – the subtitle manages to be both cheesy and misleading – bad Penguin!

I feel I should have found this novel much more depressing I did. Julia is a woman whose looks are fading, an impending disaster for her, as she has no money and lives off the handouts of lovers who will find her easier to discard the older she gets. At the moment she has an ambiguous quality:

“Her career of ups and downs had rubbed most of the hallmarks off her, so that it was not easy to guess at her age, her nationality, or the social background to which she properly belonged.”

People tend to judge her harshly rather than kindly, particularly because she is a woman and at a time of more rigid social rules, they can read her lifestyle in her clothes, hair and makeup. The men who use her escape more lightly, such as the titular lover with whom her relationship is breaking down:

“He was of the type which proprietors of restaurants and waiters respect. He had enough nose to look important, enough stomach to look benevolent. His tips were not always in proportion with the benevolence of his stomach, but this mattered less than one might think.”

After her cheques from Mr Mackenzie stop, Julia returns to England from France. Not quite estranged from her family but not on fond terms with them either, she lives in seedy Bloomsbury boarding houses:

“But really she hated the picture. It shared, with the colour of the plush sofa, a certain depressing quality. The picture and the sofa were linked in her mind. The picture was the more alarming in its perversion and the sofa the more dismal. The picture stood for the idea, the spirit, and the sofa stood for the act.”

I find that an astonishing piece of writing. To take a description of a dilapidated room and show how that reflects the mood of the person in it is one thing, but to extend it in such a way, so original and startling, really demonstrates why Rhys deserves to be lauded.

Julia ricochets around London, trying to find a man to take care of her. Rhys does not judge her protagonist which must have been quite shocking for 1930. Julia is sexually active, unmarried, childless, and is not punished by Rhys for such deviation from the feminine ideal. While she is a sad figure, even tragic, Rhys shows how we share a commonality with Julia rather than marking her out as Other.

“She was crying now because she remembered that her life had been a long succession of humiliations and mistakes and pains and ridiculous efforts. Everybody’s life was like that. At the same time, in a miraculous manner, some essence of her was shooting upwards like a flame. She was great. She was a defiant flame shooting upwards not to plead but to threaten. Then the flame sank down again, useless, having reached nothing.”

After Leaving Mr Mackenzie is a sad novel, but what keeps it from being depressing, for me, are the gentle touches of Rhys’ humour, such as in the description of Mr Mackenzie, and the fact that Julia holds on to her resilience. She is not a victim, despite being treated appallingly, but rather a realist, who knows that her options as a woman in her circumstances are limited. Rhys has a great deal to say but does so in a non-didactic way, leaving the reader to reach their own conclusions.

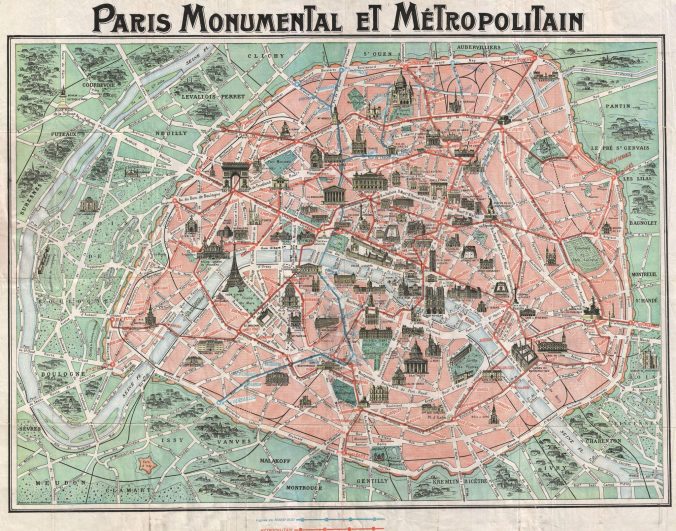

Secondly, Good Morning Midnight (1939). Superficially, this sounds very similar to After Leaving Mr Mackenzie: Sasha Jansen returns to Paris alone and broke. She is losing her looks and feels lonely and desperate… but it is quite different.

Sasha does not flail around trying to extract money from everyone. Rather, Rhys writes this novel in the first person, using a degree of stream of consciousness to explore how a single woman at this point in history comes to terms with her life and the future that awaits her. Sasha is fragile:

“On the contrary, it’s when I am quite sane like this, when I have had a couple of extra drinks and am quite sane, that I realise how lucky I am. Saved, rescued, fished-up, half-drowned, out of the deep, dark river, dry clothes, hair shampooed and set. Nobody would know I had ever been in it. Except, of course, that there always remains something. Yes, there always remains something…”

She is self-destructive and lonely:

“I’ve had enough of these streets that sweat a cold, yellow slime, of hostile people, of crying myself to sleep every night. I’ve had enough of thinking, enough of remembering. Now whisky, rum, gin, sherry, vermouth, wine with the bottles labelled ‘Dum vivimus, vimamus….’ Drink, drink drink…As soon as I sober up I start again. I have to force it down sometimes…Nothing. I must be solid as an oak.”

And yet, amidst the sadness, there is resilience. We learn of Sasha’s past in Paris as she walks the streets, meets new people and is drawn back into her memories. The stream of consciousness and flitting between past and present is a highly effective. Rather than feeling like a contrived literary style, Rhys is able to create a real sense of being inside Sasha’s head and how someone would think: not in straight lines but (to steal an analogy from Jeanette Winterson) in spirals, back and forth.

Image of 1930s Paris map from here

Based on these two novels, I would say Rhys is brilliant at creating flawed, vulnerable women who are somehow survivors – they have a strength which is not immediately obvious, that perhaps they don’t even recognise themselves.

“I am trying so hard to be like you. I know I don’t succeed, but look how hard I try. Three hours to choose a hat; every morning an hour and a half trying to make myself look like everybody else. Every word I say has chains around its ankles”

A single woman with a sexual history who is no longer young does not have the most rosy prospects in interwar society and Rhys does not shy away from this. However, there is a sense that Sasha (and Julia) is not alone in her struggles. The search for meaning in a society that can degrade through disregard affects many and there is fellowship and sympathy to be found.

“I look thin – too thin – and dirty and haggard, with that expression that you get in your eyes when you are very tired and everything is like a dream and you are starting to know what things are like underneath what people say they are.”

Wiki tells me that when first published, (male?) critics found this novel well written but too depressing. I thought it was beautifully written and sad, but not depressing. I think for me depressing comes with a certain bleakness, and I didn’t find either novel bleak: neither Julia or Sasha ever quite lose hope.

To end, if anyone can capture the vicissitudes of a life well-lived in Paris: