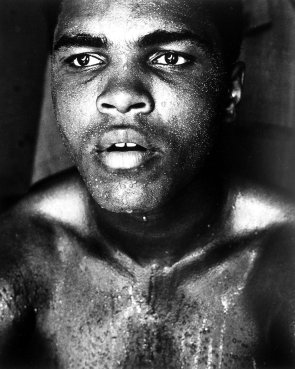

As usual, I’m a bit behind the times: here is my post to commemorate the death of Olympian/activist/philanthropist/iconic legend Muhammad Ali on 3 June, whose memorial was last Friday.

Image from here

I thought I would therefore theme this post around ‘greatest’. Just over a week ago Lisa McInerney won this year’s Bailey’s Prize for her debut novel The Glorious Heresies, so I’ve decided to look at Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie which won the Baileys (then the Orange) in 1997 and was chosen as the prize’s Best of the Best in 2015. I’ve paired it with Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie which won the 1981 Booker, and then in 1993 (25 years of the Booker) and 2008 (40 years of the Booker), it won the Best of the Bookers (the latter by public vote). They are also two more stops on my Around the World in 80 Books Reading Challenge, hosted by Hard Book Habit– away we go!

Half of a Yellow Sun is set in Nigeria during the civil war of the 1960s, when there was an attempt to establish Biafra as an independent nation. Focusing on two sisters, Olanna and Kainene, their partners Odenigbo and Richard, and Olanna and Odenigbo’s houseboy Ugwu, the war is explored through its varied but monumental impact on all their lives.

Before the war, Olanna and Odenigbo live a privileged middle class life in the university town of Nsukka, entertaining in the evenings with friends who debate issues of post-colonial identity:

“‘I am Nigerian because a white man created Nigeria and gave me that identity. I am black because the white man constructed black to be as different from as possible from his white. But I was Igbo before the white man came.’”

Ugwu joins them and is mesmerised by their sophistication, and the worlds they open for him through the books they provide. However, Adichie shows that the legacy of colonialism is deep-rooted:

“Master’s English was music, but what Ugwu was hearing now, from this woman, was magic. Hers was a superior language, a luminous language, the kind her heard on Master’s radio, rolling out with clipped precision. It reminded him of slicing a yam with a newly sharpened knife, the easy perfection in every slice.”

As the Igbo people try to establish Biafra and civil war escalates, Olanna, Odenigbo and Ugwu’s lives are ripped apart and Adichie does not pull her punches. There is forced conscription, rape as a weapon, starvation and mutilation. However, there is also reconciliation between the estranged sisters, and Adichie’s focus is not on horrors but on how the human spirit survives against overwhelming odds:

“The war would continue without them. Olanna exhaled, filled with frothy rage. It was the very sense of being inconsequential that pushed her from extreme fear to extreme fury. She had to matter. She would no longer exist limply, waiting to die.”

Adichie is a hugely popular and successful author, and I feel the hype is fully deserved: she’s a brilliant writer. I whizzed through this book – she manages to write a compelling, political, angry, compassionate and highly moving page-turner. What a feat.

Half of a Yellow Sun was adapted into a film in 2013, apparently not that successfully despite a seemingly perfect cast including smoking hot eye candy hugely talented actor Chiwetel Ejiofor:

On to Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie (1981) which like Half of a Yellow Sun was the author’s second novel: so much for the ‘difficult second novel’ theory. It’s taken me about twenty years to read Midnight’s Children, which works out as 6% of a page per day. It’s been quite a ride.

I jest of course, but it did take me 3 goes spread over 20 years to get into this novel. Normally I would have resigned it to the DNF pile (which is tiny, my TBR aspires to be that size one day – never going to happen) but I kept persevering because people who loved it really loved it and it always cropped up on various book lists (including Le Monde’s , which forms one of my reading challenges).

Now that I’ve read it, I can’t say I loved it – something about Rushdie’s style meant this was always a tough read for me – but I did find it impressive. Midnight’s Children is hugely ambitious, tackling themes around nation-making, history writing, colonialism and culture. Seemingly impossible within one novel, but Rushdie and his massive brain are clearly equal to the task. The story is narrated by Saleem Sinai who is born on the stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947, the exact moment that India gained independence from Britain.

“Thanks to the occult tyrannies if those blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades, there was to be no escape.”

Saleem’s story, and that of his family, becomes the story of the nation of India. The novel makes heavy use of magical realism, and I think this is Rushdie’s masterstroke. It would be impossible to explore such enormous themes and multiple events if the novel were entirely grounded in a recognisable reality. By allowing for magic realism, Rushdie can take the story in any direction he needs to.

Saleem discovers that all the children born into India between midnight and 1am on the day of Independence have special powers – his own being telepathy, powered by his enormous nose and blocked sinuses (told you there was magic realism).

“the children of midnight were also the children of the time: fathered, you understand, by history. It can happen. Especially in a country which is itself a sort of dream.”

“Midnight has many children; the offspring of Independence were not all human, Violence, corruption, poverty, generals, chaos, greed and pepperpots…I had to go into exile to learn that the children of midnight were more varied than I – even I – had dreamed.”

Saleem is a self-acknowledged unreliable narrator. His memory fails him at times, regarding both events in his own life and those in the wider political history of India. What Rushdie is questioning is the narratives we are all within – family, nation, history, culture – and how there is no one reality for any of us.

“Family history, of course, has its proper dietary laws. One is supposed to swallow and digest only the permitted parts of it, the halal portions of the past, drained of their redness, their blood. Unfortunately this makes the story less juicy, so I am about to become the first and only member of my family to flout the laws of halal. Letting no blood escape from the body of the tale, I arrive at the unspeakable part; and, undaunted, press on.”

I realise I may have made Midnight’s Children sound like a heavy read, and in some ways it is, but it also has a gentle humour running through it to lighten the tone. I’ve certainly never read anything else like it.

“One day, perhaps, the world may taste the pickles of history. They may be too strong for some palates, their smell is overpowering, tears may rise to eyes; I hope nevertheless that it will be possible to say of them that they possess the authentic taste of truth”

To end, I can’t help wishing the dress code for book award ceremonies was monochrome cat suits and that winners collected their awards by emerging from a fog of dry ice: