Happy St Patrick’s Day! To celebrate this day, and to participate in Reading Ireland Month hosted by Cathy at 746 books and Niall at Raging Fluff , I’ve picked one novel from my TBR mountain which was also on Cathy’s 100 Irish Novels list and a poem by one of my favourite contemporary Irish poets . This will also be one more stop on my Around the World in 80 Books Reading Challenge, hosted by Hard Book Habit.

Firstly, The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch which won the Booker in 1978. This was recommended to me by my sixth form English tutor, which means it’s been on my TBR for *cough* 20 years *cough*. Oh dear. I got there eventually. Charles Arrowby, theatre director, decides to retire to the coast:

“The sea is golden, speckled with white points of light, lapping with a sort of mechanical self-satisfaction under a pale green sky. How huge it is, how empty, this great space for which I have been longing all my life.”

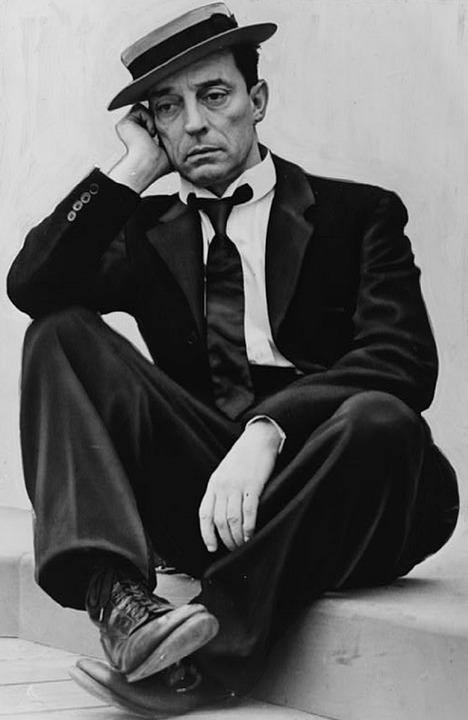

Arrowby is vain, arrogant, solipsistic, self-aggrandizing… He views himself as some sort of Prospero figure:

Image from here

But of course he isn’t a magician, he has no more power than anyone else. The titular force of nature that surrounds him acts as a reminder of this, indifferent and formidable.

“the sea was a glassy slightly heaving plain, moving slowly past me, and as if it were shrugging reflectively as it absent-mindedly supported its devotee”

It isn’t long before his self-induced exile starts to unravel. He starts to have hallucinations about sea monsters and within this unstable psychology is the constant background obsession with his teenage love, Hartley. By odd coincidence, she now lives in the same village with her husband, and all of Arrowby’s delusions become focused on her, as he is unable to conceive of anything that won’t fit in with his own needs:

“I reviewed the evidence and I had very little doubt about what it pointed to. Hartley loved me and had long regretted losing me. How could she not?”

The Sea, The Sea is an extremely clever novel, carefully balancing Arrowby’s delusions on a precipice between comedy and terror:

“ ‘There’s an eternal bond between us, you know there is, it’s the clearest thing in the world, clearer than Jesus. I want you to be my wife at last, I want you to rest in me. I want to look out for you forever, until I drop dead.’

‘I wish I could drop dead.’

‘Oh shut up –‘ “

I was never sure which way it would go, how violently it would all unravel, or whether it would resolve in a subdued, sad way. Arrowby’s quiet, introspective (possible spy) cousin is the voice of reason, resolutely ignored:

“You’ve built a cage of needs and installed her in an empty space in the middle. The strong feelings are all around her – vanity, jealousy, revenge, your love for your youth – they aren’t focused on her, they don’t touch her. She seems to be their prisoner, but really you don’t harm her at all. You are using her image, a doll, a simulacrum, it’s an exorcism.”

The Sea, The Sea is a novel that tackles major themes: the nature of love, the meanings we attach to our lives, how we decide what is real when we can only view from our own perspective, how we recognise what really matters. Arrowby’s narcissism is contemptible, but the skill of Murdoch’s writing shows him as an everyman (despite his belief in his own extraordinariness) and places us in a position where to judge him harshly is to judge ourselves:

“Time, like the sea, unties all knots. Judgements on people are never final, they emerge from summings up which at once suggest the need for reconsideration. Human arrangements are nothing but loose ends and hazy reckoning, whatever art may pretend in order to console us.”

Secondly, Why Brownlee Left by Paul Muldoon, the titular poem from his 1980 collection. Muldoon’s poems can be difficult to comprehend and contain head-scratchingly obscure references, but he is also humorous and playful, and takes such clear joy in language that I think any new collection from him is cause for excitement. The poem I’ve chosen is one of his most accessible but still leaves plenty of space for the reader to decide on meaning; it contains Muldoon’s gentle humour, and it’s all tied together with expert use of rhythm and echoing half-rhyme – I hope you like it 🙂

Why Brownlee left, and where he went,

Is a mystery even now.

For if a man should have been content

It was him; two acres of barley,

One of potatoes, four bullocks,

A milker, a slated farmhouse.

He was last seen going out to plough

On a March morning, bright and early.

By noon Brownlee was famous;

They had found all abandoned, with

The last rig unbroken, his pair of black

Horses, like man and wife,

Shifting their weight from foot to

Foot, and gazing into the future.

Do join in with Reading Ireland month aka the Begorrathon, and if you’re not a Luddite like me you can also check out their Facebook page 🙂

To end, as I read a review of a new Phil Lynott biography over the weekend, here are Thin Lizzy singing their version of a traditional Irish song: