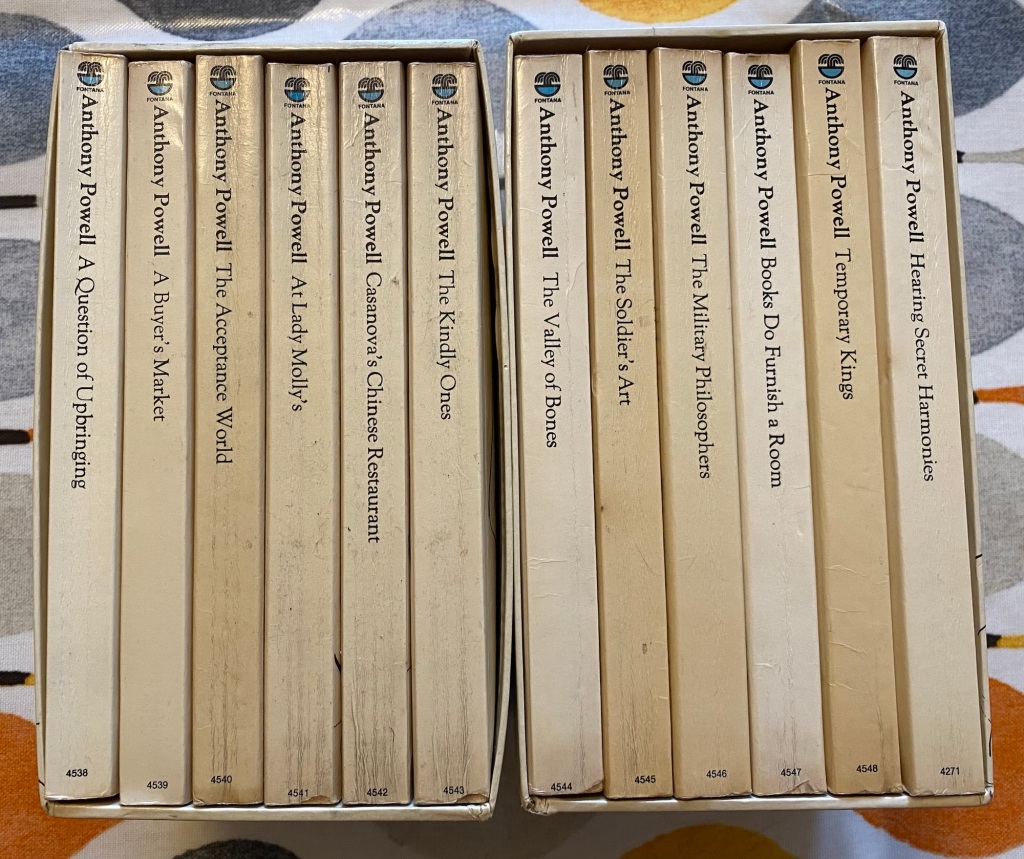

I’ve decided that 2024 will be the year of a reading project I’ve been considering for a while – a book per month throughout the year from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

What’s that you say? I have half-completed reading projects still languishing? I have a spiralling TBR that doesn’t need 12 more books added to it? Be gone! You are clearly a pragmatist and such attitudes have no place in my reading life 😀

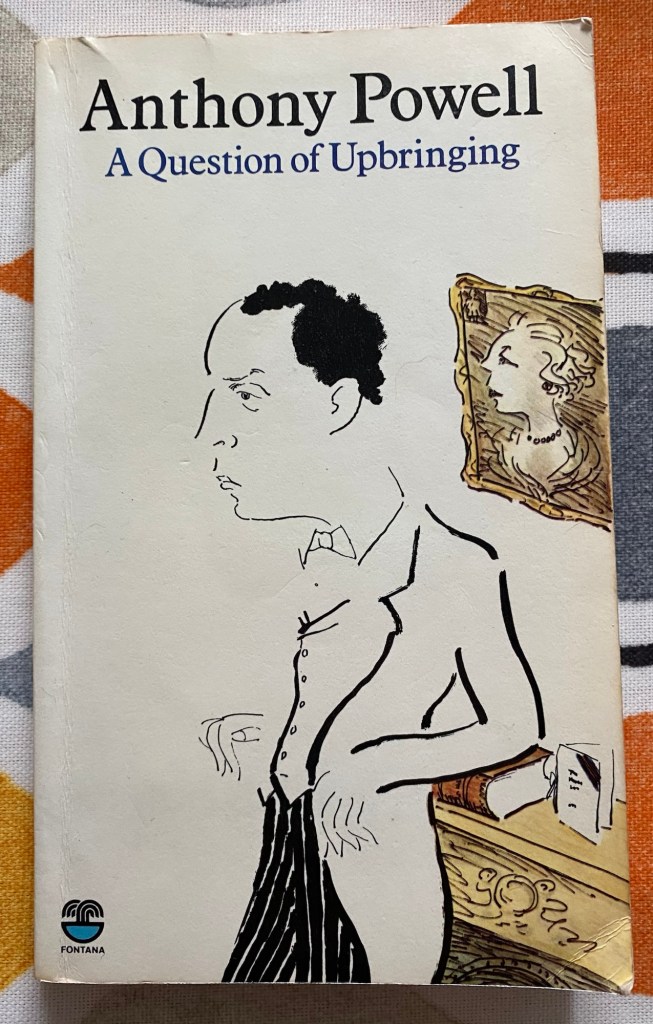

In the first novel, A Question of Upbringing (1951), we follow Nick Jenkins from his school days at a thinly-disguised Eton to his university days at a thinly-disguised Balliol College, Oxford. Starting at School, we meet Jenkins’ friends Stringham and Templer, and hear of their frustrations with housemaster Le Bas.

“’He started life as a poet,’ Stringham said. ‘Did you know that? Years ago, after coming back from a holiday in Greece, he wrote some things he thought were frightfully good. He showed them to someone or other who pointed out that, as a matter of fact, they were frightfully bad. Le Bas never got over it.’

‘I can’t imagine anything more appalling than a poem by Le Bas,’ said Templer, ‘though I’m surprised he doesn’t make his pupils learn them.’

‘Who did he show them to?’ I asked.

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ said Stringham. ‘Henry James, or Robert Louis Stevenson, or someone like that.’”

The boys are varying degrees of privileged, from uber-wealthy to moderately wealthy, from landed gentry to new money. The societal hierarchies are complex and imperfectly understood, even by those in their midst:

“Clearly some complicated process of sorting out was in progress among those who surrounded me: though only years later did I become aware of how early such voluntary segregations begin to develop; and of how they continue throughout life.”

In theory I have limited patience for such stories, after the enormous damage Eton-educated men and their cronies have done in UK politics. Yet I found myself enjoying A Question of Upbringing. I think because Powell doesn’t suggest the superiority of anyone he’s writing about or the systems in place, casting a satirical eye over it all.

For example, when Nick begins his travels, he finds himself hopelessly ill-equipped to comprehend any culture beyond his own:

“I had seen a provincial company perform The Doll’s House not many months before, and felt, with what I now see to have been quite inadmissible complacency, that I knew all about Ibsen’s countrymen.”

It is during these travels that he meets Widmerpool again, a boy somewhat disregarded as figure of fun at school, who shows himself to be more astute than Nick and the other pupils allowed for.

“Later in life, I learned that many things one may require have to be weighed against one’s dignity, which can be an insuperable barrier against advancement in almost any direction.”

Nothing of huge significance seemingly happens in A Question of Upbringing, but it wouldn’t surprise me if events somehow cast a long shadow in later volumes. As a standalone novel, Powell keeps the narrative compelling by picking out certain moments and impressions, rather than plodding through years with equal weighting. It’s a short novel, only 223 pages in my edition and this length worked well – satisfying but also with a sense of setting the scene for later novels.

It took me a while to adjust to Powell’s dense writing style; he likes long sentences of several clauses. Once I had got used to this though, I found myself swept along.

“The evening was decidedly cool, and rain was half-heartedly falling. I knew now that this parting was one of those final things that happen, recurrently, as time passes: until at last they may be recognised fairly easily as the close of a period. This was the last I should see of Stringham for a long time. The path had suddenly forked. With regret, I accepted the inevitability of circumstance. Human relationships flourish and decay, quickly and silently, so that those concerned scarcely know how brittle, or how inflexible, the ties that bind them have become.”

Nick is an enigmatic narrator. In this first volume he describes many people and events, observes whole scenes, without appearing to have spoken or acted himself at all. We learn very little about him. I found myself wondering why Powell had opted for an omnipresent narrator over an omniscient one, when Nick barely seems present. But that’s not a criticism, just what seemed a curious choice. Maybe Nick will emerge from his own story in the subsequent volumes. I’m looking forward to finding out.

To end, a dance from the 1950s, looking back to the 1920s: