This my contribution to Reading Ireland Month 2023, aka The Begorrathon, running all month and hosted by Cathy over at 746 Books. Do head over to Cathy’s blog to check out all the wonderful posts so far!

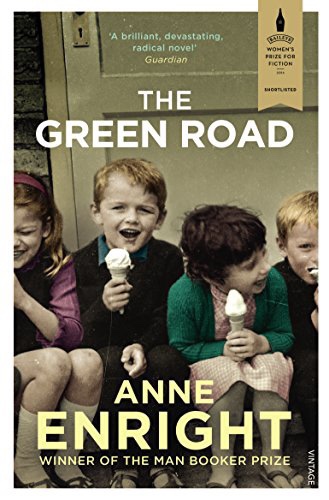

Anne Enright’s The Green Road (2015) has been languishing in the TBR for many years. I’m trying to get to grips with the toppling monster (hahahaha) as I had to acknowledge that any gains made in my book-buying ban of 2018 had been completely undone. So I’m really pleased this year’s Begorrathon finally prompted me to pull it from the shelf.

The Green Road is divided into two parts, Leaving, and Coming Home. The first part considers one of four siblings in turn, from 1980 onwards. Hanna as a small tearful child; Dan gradually emerging from the closet in 1991’s New York; Constance having a cancer scare back home in County Limerick in 1997; Emmet pursuing aid work in Mali in 2002.

Through each of these sections we learn about the individual, but also gain an emerging picture of the family, including their tempestuous self-focussed mother Rosaleen and silent father Pat. This means that when they all return home at the behest of widowed Rosaleen in 2005, we have a good idea of each of them and it’s intriguing to see how Christmas dinner will play out when they are all in the same room. The focus will be on the five rather than extended family:

“The only route to the Madigans Christmas table was through some previously accredited womb. Married. Blessed.”

The adult children approach the event with no small degree of trepidation. Rosaleen is not an easy woman. Demanding without explicitly stating what her demands are, while judging her children quite harshly. She doesn’t approve of Constance’s weight gain:

“Rosaleen believed a woman should be interesting. She should keep her figure, and always listen to the news.”

Or Dan’s values, influenced by his work in the art world:

“For an utterly pretentious boy, he was very set against pretension. Much fuss to make things simple. That was his style.”

Yet she loves them deeply and they must attend, for Rosaleen is threatening to sell the family home:

“Rosaleen was living in the wrong house, with the wrong colours on the walls, and no telling anymore what the right colour might be, even though she had chosen them herself and liked them and lived with them for years. And where could you put yourself if you could not feel at home in your own home? If the world turned into a series of lines and shapes, with nothing in the pattern to remind you what it was for.”

In this interview Enright says: “I don’t do plottedness. I do stories, I do slow recognition.” This is exactly it. There isn’t a lot of plot in The Green Road but it is such a compelling read. The characterisation is complex and wholly believable, with all of the family not behaving entirely well nor entirely badly. The relationships are so delicately drawn, with their mix of love and frustration, familiarity and the unknown, wonderfully evoked.

“Emmet closed his eyes and tilted his face up, and there she was: his mother, closing her eyes and lifting her head, in just the same way, down in the kitchen in Ardeevin. Her shadow moving through him. He had to shake her out of himself like a wet dog.”

I read The Green Road over a few hours and was sorry to come to the end, but it was perfectly paced and a wholly satisfying read. Enright is such a wonderful writer, able to articulate the small moments in life that can have such an impact even when they are barely recognised. She perfectly captures the immensity of the every day.

“She looked to her son, she looked him straight in the eye, and for a moment, Emmet felt himself to be known. Just a glimmer and then it was gone.”

You can read an interview with Enright talking about The Green Road here.

To end, an Irish film about family which I’ve enjoyed in the last week is the Oscar-winning An Irish Goodbye. For those of you who can get iPlayer, it’s available and only 23 minutes long (warning: there is a dead hare in the road – not gory – in the first few seconds of this trailer);