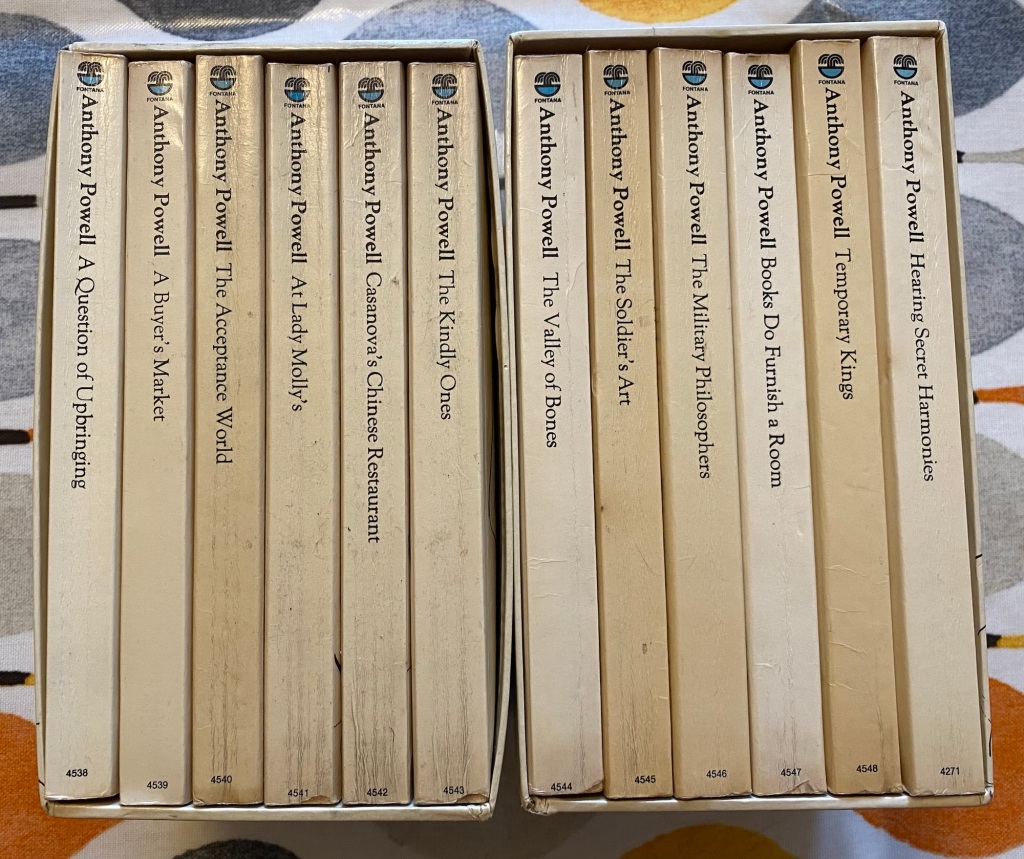

I did it! This is the final instalment in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. I’d been put a bit behind by labyrinthitis but I finished on 31 December. I’d hoped to write and post this the same day but I got distracted by my Christmas jigsaw puzzle on The World of Virginia Woolf 😀

Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself. The twelfth volume, Hearing Secret Harmonies, was published in 1975 and opens in 1968.

Much of Hearing Secret Harmonies is concerned with the past but it opens by introducing a new character, the sinister Scorpio Murtlock who is camping on Nick and Isobel’s land with some of his followers. Nick, always such an astute observer of people, is not taken in by Murtlock’s charisma:

“When Murtlock smiled the charm was revealed. He was a boy again, making a joke, not a fanatical young mystic. At the same time he was a boy with whom it was better to remain on one’s guard.”

“Murtlock himself possessed to a marked degree that characteristic – perhaps owing something to hypnotic powers – which attaches to certain individuals; an ability to impose on others present the duty of gratifying his own whims.”

It’s a masterstroke of Powell’s writing that while Murtlock remains elusive, he is also deeply unnerving. There’s no doubt as to how dangerous he could be, fully realised by the novel’s end.

Nick then attends two dinners which work well as devices for him to meet past friends and acquaintances, drawing them into the final sequences, and alerting the reader as to has left the Dance for good. There is a sense of time folding in on itself:

“Members, his white hair worn long, face pale and lined, had returned to the Romantic Movement overtones of undergraduate days.”

And of course Widmerpool, Nick’s talisman of sorts, reappears. He is quite extraordinary: a former beacon of the Establishment now refuting his knighthood, asking to be called Ken, wearing a grubby red polo neck to formal occasions and focussing on the power of 1960s youth movements for societal change. His involvement with Scorpio Murtlock seems inevitable…

This final volume works well in balancing reflections of the past without becoming overly contrived. There is a sense of reflection occurring organically, without being maudlin, sentimental or nostalgic. Powell is far too astute and insightful for the ending to take such tones.

There’s also a great deal of humour, from larger set pieces with Murtlock’s naked dancing cult providing a bathetic contrast with the central image of the novel sequence:

“It was not quite the scene portrayed by Poussin, even if elements of the Season’s dance was suggested in a perverted form; not least by Widmerpool, perhaps naked, doing the recording.”

To smaller moments such as disagreement over paintings at a retrospective of Deacon’s work:

“Well Persepolis isn’t unlike Battersea Power Station in silhouette.”

And Nick’s various assessments of himself:

“Pressures of work, pressures of indolence.” (my life frustrations in a sentence!)

“These professional reflections, at best subjective at worst intolerably tedious,”

I have really enjoyed reading A Dance to the Music of Time and it hasn’t been an arduous undertaking at all. I’m sure it will reward re-reading; there are so many allusions and subtleties that have certainly passed me by. For me, the sequence peaked with the war trilogy, but each novel held its own joys, working on an individual level as well as part of a whole sequence. I’m going to really miss Nick, even though he remained half-hidden to me throughout the twelve volumes.

“Two compensations for growing older are worth putting on record as the condition asserts itself. The first is a vantage point gained for acquiring embellishments to narratives that have been unfolding for years beside one’s own, trimmings that can even appear to supply the conclusion of a given story, though finality is never certain, a dimension always possible to add.”