I wasn’t planning on posting this week, as I have two exams on Thursday, and despite the fact that I am a major procrastinator I’m really trying to revise. (And keep getting distracted by episodes of Cake Boss, of which there seem to be approximately twenty million. If I end up answering a question with the phrase “Byron is prime example of poetry in the Hoboken style, baby!” I have only myself to blame. A little in-joke there for anyone else who follows this extraordinary bake-fest.)

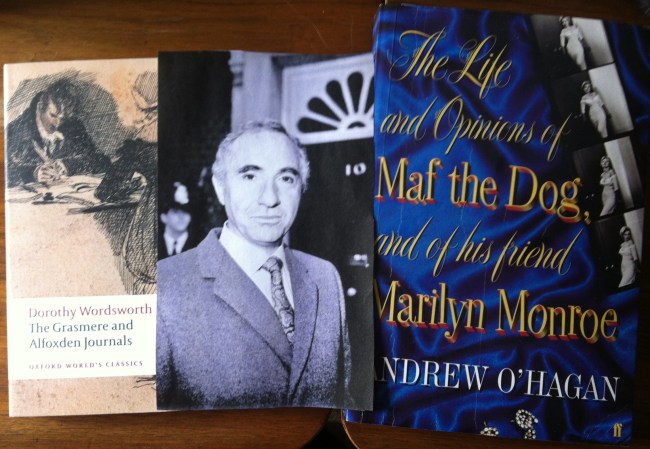

Anyway, I wanted to post to commemorate the work of Seamus Heaney, whose death was announced today. This is a sad loss to the contemporary poetry scene. Heaney was as extraordinarily sensitive poet, dedicated to his craft, alive to all the possibilities of language. To see him interviewed was the opportunity to listen to someone intelligent, unpretentious and engaging.

I’ve picked two of his poems pretty much at random. He was a prolific writer so even if you don’t think much of my choices do check him out, there’s bound to be something for you.

Firstly, Blackberry Picking. I chose this poem because I’m pretty sure this was the first Heaney poem I ever read, at school. My English teacher was a massive Ted Hughes fan, so Heaney (contemporary and friend of Hughes) wasn’t too much of a leap. You can view the whole poem here. I’m just going to look at the first ten lines, and then the end line.

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

for a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

like thickened wine: summer’s blood was in it

leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

sent us out with milk-cans, pea-tins, jam-pots

where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

I love his imagery here. I grew up with blackberries at the bottom of my garden and to me this vividly evokes that memory, but also his use of language is so accessible. Sometimes contemporary poetry (or any poetry) can seem so impenetrable. Heaney is great communicator, and I think this poem is easy to understand. That’s not to say it’s simple – there’s a violence to this childhood memory, created through the visceral imagery (clot/flesh/blood/lust/scratched) that unnerves me, and stops it being a straightforward nostalgia trip. Heaney’s last lines are often powerful and punchy endings. In Blackberry Picking it’s this:

Each year I hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.

I think this is so simple and beautiful. It succinctly captures the sadness that tinges childhood memories, and the way we learn that the world is not always as we want it to be, or something we can control. I don’t want to go on too much because I think poetry is an intensely personal experience, and everyone sees and gains different things from it. I hope its enough of a taster to encourage you to check out the full poem.

Secondly, Two Lorries. This is quite a famous poem of Heaney’s, from his Whitbread Award winning collection The Spirit Level, published the year after he won the Nobel Prize. I chose it because there’s a recording of Heaney reading the poem available online, here. What better way to experience the poem? This is one of the poems where Heaney looks at the Troubles that have been the enduring political experience of his country in his lifetime. Here are the first two stanzas:

It’s raining on black coal and warm wet ashes.

There are tyre-marks in the yard, Agnew’s old lorry

Has all its cribs down and Agnew the coalman

With his Belfast accent’s sweet-talking my mother.

Would she ever go to a film in Magherafelt?

But it’s raining and he still has half the load

To deliver farther on. This time the lode

Our coal came from was silk-black, so the ashes

Will be the silkiest white. The Magherafelt

(Via Toomebridge) bus goes by. The half-stripped lorry

With its emptied, folded coal-bags moves my mother:

The tasty ways of a leather-aproned coalman!

This shows Heaney’s great skill at capturing life experience: the voices of his mother and the coalman are so clear and direct, despite being indirectly quoted. Once again, I find his imagery so beautiful, and disturbing. The idea that the coal turns from one extreme to the other (silk-black to silkiest white) is an image that has so much to say, and the extremity is evoked within a resolutely domestic scene gives it an extended context that makes it personal and political. The second lorry of the title is the one that blows up the bus station in Magherafelt. Here’s the end of the poem:

So tally bags and sweet-talk darkness, coalman,

Listen to the rain spit in new ashes

As you heft a load of dust that was Magherafelt,

Then reappear from your lorry as my mother’s

Dreamboat coalman filmed in silk-white ashes.

I’ve said before that I find it hard to write about things I really love. This is one of those times. The end of that poem is incredibly powerful and moving, I think I’ll just let it speak for itself.

Seamus Heaney 1939-2013.

Image taken from: http://www.laobserved.com/archive/2013/08/seamus_heaney_nobel_prize.php