For the second week running Groucho provides the title of my post – I try not to quote the same person so close together, but it was really hard to find a quote about fathers that had the right air of flippancy that I try to cultivate for this blog. 16 June was Father’s Day in many countries and so both of the books I’ve chosen are around this theme. However, my search for quotes about fathers showed me it’s a potentially tricky subject for people, so neither of the novels are precisely about fathers, more about the role of fathers and the impact that has. Also, my own father has always proclaimed that Father’s Day is a commercial scam and instructed his offspring not to engage with it, which means I feel a bit disloyal even mentioning it. So the theme of this post is Father’s Day, sort of…

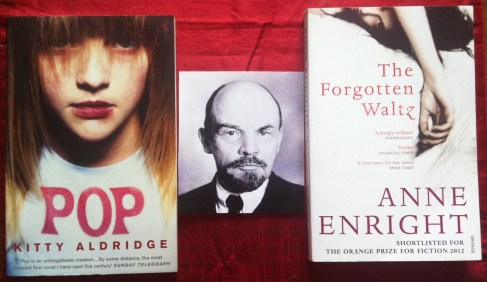

Firstly, The Forgotten Waltz by Anne Enright (2011, Vintage). Enright has a sparse writing style that I love, and I highly rate her 2007 novel The Gathering, which won the Man Booker Prize. The Forgotten Waltz explores many of the same themes – families, what damage they do, the lies and intricacies that can make up adult lives. If that sounds really depressing, well, it’s not exactly a heart-warming read, but it’s not downbeat, just very real. I chose it for Father’s Day because the narrator identifies her lover’s role as a father as the motivating force in their lives from the opening paragraph:

“If it hadn’t been for the child then none of this might have happened, but the fact that a child was involved made everything that much harder to forgive. Not that there is anything to forgive of course, but the fact that a child was mixed up in it all made us feel that there was no going back; that it mattered. The fact that a child was affected meant we had to face ourselves properly, we had to follow through.”

The thing that happens is an extra-marital affair, and the child is Evie, who witnesses the narrator, Gina, kissing her father. You’ll note Gina believes there was “nothing to forgive”, which is somewhat questionable – when deceit is involved, people get hurt in the fallout. But I think this one of the strengths of the novel, that there are not easy characters (like the intermittently self-deluding Gina) or situations, no “goodies” or “baddies”. It’s all shades of grey (by which I mean morally complex, not badly written BDSM tales).

The reality of the situation is also reflected in the structure of the narrative, which although essentially linear, jumps back and forth, as people do when they’re telling you their story. It accurately reflects the complexities of our lives, the way we restructure our narratives as we try and make sense of things; things that can appear different to us on different days: “This is the real way it happens, isn’t it? I mean in the real world there is no one moment when a relationship changes, no clear cause and effect.” There’s no huge driving plot here, in that sense it is a very simple tale, but Enright’s great skill is to capture small moments and attempt to define their importance:

“When the last small guest was gone and the rubbish bag full of packaging and uneaten lasagne the thought of him – the fact of him – happened in my chest, like a distant disaster. Something was snapped or broken. And I did not know how bad the damage was.”

The Forgotten Waltz is an acutely insightful novel, that at the same time steps back from offering the answers – honest and thought-provoking.

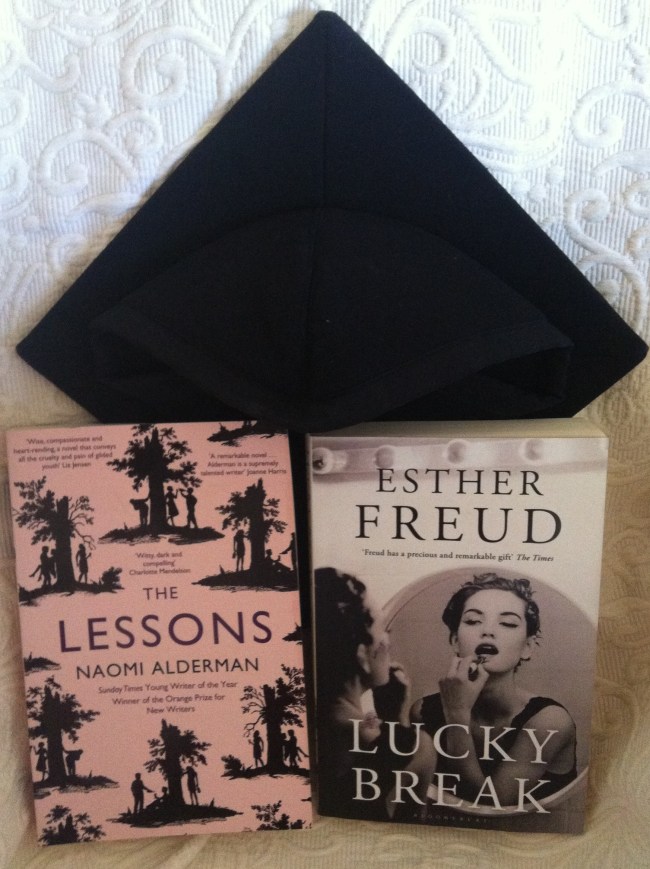

Secondly, Pop by Kitty Aldridge (2001, Vintage). Pop was Kitty Aldridge’s first novel (she’s an actress who has been friends with fellow thesp-turned-author Esther Freud since their days at drama school, literary fact-fans) and looking on amazon people seem to object to the abundance of imagery in the novel, which I think is understandable in your first attempt. I like an abundance of imagery so it didn’t bother me at all, and I found the story of Maggie, parentless at thirteen, going to live with her trivia-loving granddad in the Midlands in 1975, a touching and compelling read. The opening paragraph introduces us to Maggie’s new parental figure:

“She is looking up at a tall man in shambolic clothes. He is racing-dog thin with a long mischievous face, whiplashed with creases. The railway-station wind lifts his remaining hair. It is hard to say how old he is; old, seventy perhaps. But he moves with the quick fluidity of a youth and hangs a lean on one hip like a gunslinger. When he is not squinting he has the openly amazed expression of a child. His eyes are a shocking shade of blue; they steal almost all the available light. Maggie follows, up into his eyes like the light.”

The book follows Pop and Maggie as they grow used to each other. The plot is slight – Pop wants to win the local pub quiz:

“Pop had stayed up half the night with his facts. He knew every West Indian cricket team for the past five years. “I’ll wipe the floor with you in a sporting category any day Malcolm Denton!” he hollered as he shaved at dawn. The statement sprang through the open window and bounced off car roofs into the trees. The birds stopped singing momentarily, considering the claim. The three of them trooped in the man-dog-child formation along Tower Road past the Pint Pot and on past Iris’s house. Iris was Pop’s exquisite, unattainable love and he was going to win her at any cost. He told himself the gallon of beer and five pounds meant nothing; winning, that was what counted.”

Gradually, the two of them, a cantankerous old man still having nightmares about the war, and a teenage girl who worries her hands are too big & the rest of her too bony, form an unlikely alliance, and a bonded family. This is what makes Pop a great Father’s Day read:

“Pop wondered about her. About how it would turn out. About what he’d said to the woman carrying a file with their names on. The stuff about family, about blood ties, all that thicker-than-water speech. The prohibitive wave of his hand to knock the alternatives into a cocked hat. The rise of blood in his temples as he moved himself to trembling, and the final whispered declaration of love for her, that he didn’t feel then but was saddled with now […] And he felt for her now alright. He laid his chin in the cradle of his free hand and closed his eyes. Buggered it again, you fool.”

Here are the books with a picture of Lenin. I realise I need to explain this, dear reader. They are with Lenin because my very own pater is the spitting image of the Bolshevik leader. So much so that when I showed him (my Dad, I don’t talk to the ghost of Lenin) the image on my phone that flashes up when he calls me, he asked “When was that taken? I look good.” And I had to break it to him that it was in fact Vladimir Ilych, not himself. Happy Father’s Day, and up the revolution!