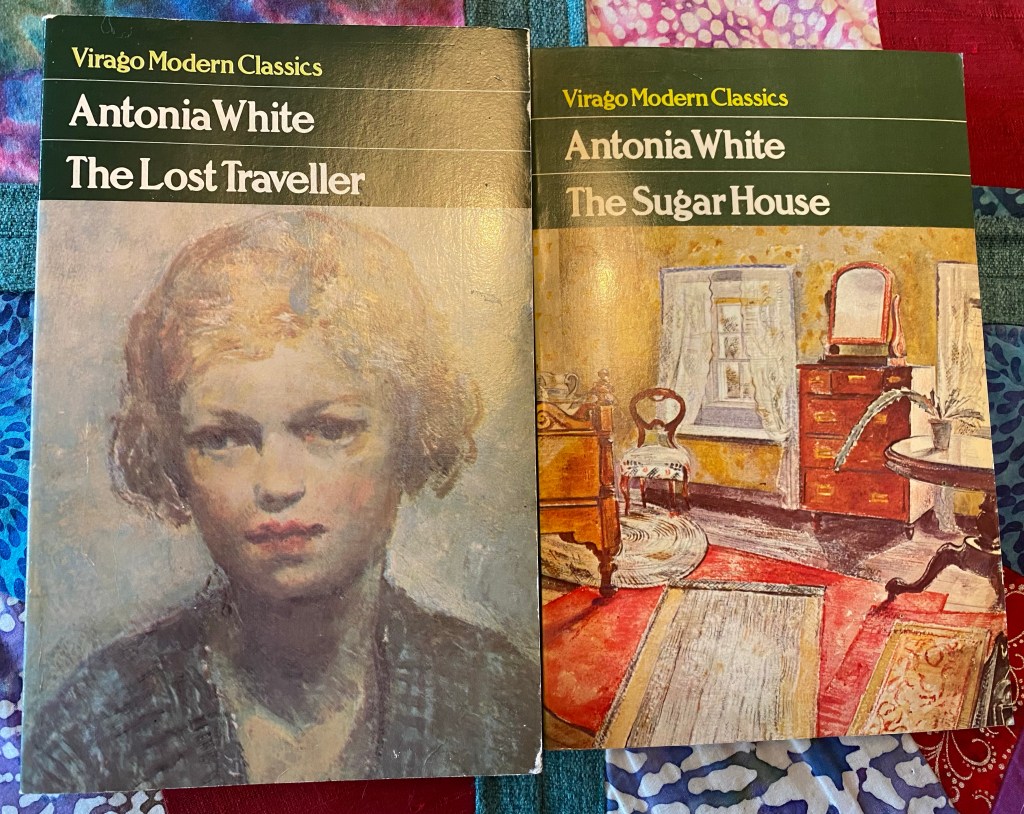

This week I’m looking at two novels by Antonia White, prompted by the pending arrival of next week’s 1954 Club, hosted by Simon and Kaggsy. When I looked at the TBR for 1954 novels, one that I had was Beyond the Glass. However, it’s the final novel in a quartet, and I hadn’t read the middle two…

It’s been six years since I read Frost in May and I’m not sure why it’s taken me so long to pick up Antonia White again, because I really enjoyed that first instalment. Frost in May was written in 1933, and White didn’t continue the story again until 1950, going on to write the last two in the quartet in 1952 and 1954.

The Lost Traveller (1950) sees Nanda from Frost in May renamed Clara and returning to her childhood home in West Kensington to attend the funeral of her paternal grandfather. Her father is bereft, but in 1914 emotions were to be controlled absolutely:

“Suddenly he was touched by an old fear of which he had never spoken to anyone, the fear that one day he might lose all control of his mind. Against that there was only one weapon; his obstinate will.”

Mr Batchelor is a teacher who harbours academic ambitions for Clara. His feckless wife Isabel wants Clara to be beautiful. She is both of these things, but not to the extent that either of her parents would like. The complex family relationships are brilliantly portrayed by White: the mismatched parents, the passive aggressive power struggles between Isabel and her mother-in-law (“Mrs Batchelor’s face … assumed a look of patient malice.”) and in the middle of it all, adolescent Clara.

“At home, to be silent was taken for a sign one was sulking.”

After her mother is ill with the mysterious women’s problems that were always so common and yet so unspoken, Clara’s father can no longer pay her school fees (the NHS was over 30 years away) and so she has to leave Catholic boarding school to attend a local Protestant school. She’s actually quite happy there, and makes two friends, although neither of them are Catholic, to the concern of her convert parents.

“Isabel, who would never have come to such a decision on her own, was willing to follow him. Catholicism seemed to her a poetical and aristocratic religion.”

Clara’s religion plays a large part in The Lost Traveller, as she tries to establish what it means for her as a young adult, away from the structures of her convent school.

Of course, with the year being 1914, readers know what the family is about to live through. However, when war breaks out, the only person it really affects is Mr Batchelor, as he sees the population of his old boys steadily wiped out.

“If only he could have gone to the front with them, he would have been completely happy.”

Although Clara prides herself on not being as vacuous as her mother, in some ways she is just as self-focussed and oblivious:

“Since she had nobody at the front in love with her and was too young to be a nurse or W.A.A.C, Clara refused to take any interest in the progress of the war.”

So while the war takes place somewhere else, Clara struggles with her sense of self, trying to work out who she is and how to manage the tumultuous feelings of teenage life in a family where so much goes unspoken. Her father is devout, strict, and given to tempers. Clara adores him and yet there is distance between them:

“Why couldn’t he understand without being told that there was nothing she would not do, cut her hair off, hold her hand to the fire, if it would bring any comfort? Why couldn’t he realise that the one impossible thing was to speak?”

Meanwhile her mother is struggling with her life choices – or lack thereof – and is drawn to one of her husband’s colleagues, Reynaud Callaghan, who encourages her romantic fancies.

“‘But I love Versailles,’ she went on dreamily. ‘I had an ancestress at the court of Louis XVI. I should have adored that life. Those exquisite clothes and the balls by candlelight and the masquerades by moonlight.’”

Isabel is great creation: vain, shallow, a snob, and yet in many ways she sees more clearly than anyone else. She tries to talk to Clara about childbirth and sex, but Clara stops her. Clara’s naivete about both is astonishing yet believable.

An opportunity comes up for Clara to be a governess for six months to an aristocratic Catholic family, which her family are keen she take up. I found her charge thoroughly unpleasant – an over-privileged, spoilt, entitled little brat. The type that grows up to run the country 😉

It’s there that Clara meets Archie Hughes-Follett, injured in the line of duty. He will come to play a much larger role in her life in The Sugar House.

“When she considered her vanity and duplicity and how little her beliefs influenced her behaviour, she began to wonder whether she might not be insensibly growing into a hypocrite.”

The Sugar House (1952) picks up Clara’s story six years later in 1920. She is an actress, having paid for her drama tuition herself with money made from working in a government office. She doesn’t seem wholly committed to her profession, but she is to her older lover Stephen Tye.

Needless to say, the reader may not be quite so enamoured of a man given to pronouncements such as: “‘No female novelist is worth reading,’ said Stephen. ‘Women can’t write novels any more than they can write poems.’” He then wheels out the tired old misogynist cliché that Branwell wrote Wuthering Heights. Sigh…

Thankfully we don’t have to endure this awful man for too long, as he ends up on a different tour to Clara. I thought the touring life was wonderfully evoked by White:

“Though towns changed, landlady’s sitting-rooms remained the same. There were always round tables with red or green serge cloths, aspidistras, photographs of seaside towns in plush frames and, in lucky weeks, a tinny, yellow-keyed piano.”

Clara often finds herself sharing rooms with fellow actor Maidie, who is at once much more devout and much more worldly than Clara. Religion is not such a strong theme throughout The Sugar House as it was in The Lost Traveller, but it is there as a constant.

When things fall apart with Stephen – as the reader knows they inevitably will – Clara returns to the security of what she knows: home, and Archie. He loves her, and unlike Stephen he respects her writing:

“I didn’t think even you could write anything which got me so much.”

However, he is conflicted and confused. He has the same childlike quality he had in The Lost Traveller, but his self-medicating with alcohol has worsened:

“Often he had sulked like a schoolboy but never had she seen him in this mood of aggressive bitterness.”

Clara doesn’t love him, but she marries him. Although Maidie has helped Clara to become less naïve, she is still hopelessly ignorant and to a modern reader the whole thing is doomed to failure. Probably to 1950s readers too, as this is Clara on her wedding day:

“She wondered if he had really expected her to run away. Her will was too paralysed even to formulate the wish.”

The titular house is their first married home, as Clara is desperate to leave the stifling atmosphere of her parents’ house. She finds a place in Chelsea, the portrayal of which is amusing for twenty-first century readers. Now it is one of the most expensive parts of London, but apparently in the 1920s it was bohemian and considerably less salubrious. This does not go down well with her upright father:

“ ‘No doubt you fill the place with short-haired women and long-haired men. Archie has all my sympathy if he prefers the public house.”

The horror!

Interestingly, what draws Clara to this atmosphere is the evidence of people working. Artists wander the streets with the tools of their trade tucked under the arms, and Clara realises she is desperate to write:

“Oh, God, don’t let me be just a messy amateur.”

However, her increasingly stressful married life where Archie fritters away money and drinks heavily means that she finds it hard to focus on work. The house, with its distempered walls that look like sugar icing, cramped rooms and two untidy people living it, begins to oppress her almost as much as her parents’ house.

“Once this sense of non-existence was so acute that she ran from the basement to the sitting room full of mirrors almost expecting to find nothing reflected in them.”

Eventually things reach a breaking point, at once dramatic and understated, entirely believable and very sad. I wouldn’t normally read books by the same author so close together, but I’m glad I did here. I’ve felt very much submerged into Clara’s world and completely involved in her story.

“Yet here, as there, she found herself both accepted and a little apart. She was beginning to wonder if there were any place where she did perfectly fit in”

All being well, Beyond the Glass next week!

(I should mention there is antisemitism expressed in both novels, particularly The Lost Traveller. However, the characters stating such views are never portrayed as admirable. I think writing in the 1950s, White was reminding a contemporary readership who would have had the holocaust in recent living memory, of the pervasiveness of racism in society).

To end, a song that sums up Clara and Archie’s situation pretty well: