Today is Bloomsday, and the centenary of the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses. I decided this meant I couldn’t put it off any longer and 2022 would be the year I finally cracked the spine on this tome (metaphorically of course – I don’t crack spines, I’m not an animal.)

When I read War and Peace back in 2017, I opted out of a review-type book post, intimidated at the thought of trying to say anything remotely coherent or interesting about such a revered novel. Instead I opted for a reading diary. Now here I am with a similarly revered, equally intimidating cornerstone of literature. There’s no way I can say anything useful about Ulysses, especially in its centenary year with all the celebratory events happening.

And so I present my Ulysses reading diary, neither coherent nor interesting! In fact, to manage any expectation of intellectual engagement with the genius of Joyce in this post, I should confess that the first hurdle I had to overcome in approaching the text was to get the Ulysses 31 theme tune out of my head (it’s probably unnecessary to explain here that I am a child of the 80s…)

Day 1

“Ulysses, Ulysseeeeees, soaring through all the galaxieeeeees….” Pesky earworm.

Normally if I’m told a book is difficult, I arrogantly assume I can do it. But Ulysses is genuinely intimidating. What I need to remind myself is:

- I really love James Joyce. Genuinely, Dubliners is one of my favourite-ever books. So I might even enjoy Ulysses.

- Other people have done it. I’ve even met some of them. Lovely bloggers left encouraging comments on my previous post where I explained what I planned to do. It’s definitely do-able.

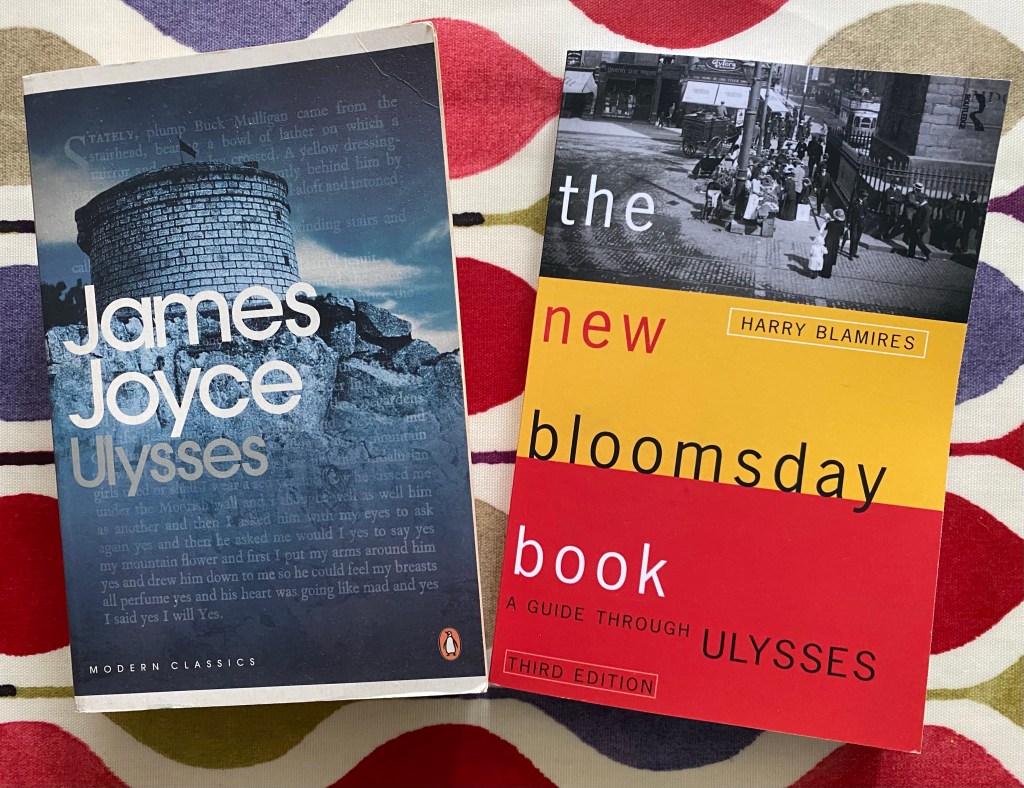

- I am not going in unarmed. I have The New Bloomsday Book: A Guide Through Ulysses by Harry Blamires (3rd ed. 1996) at my side. I’m almost certain I read on twitter that this was a good thing, and surely twitter is never wrong??

I’ve read the 80+ page introduction to my edition and now wonder if I should gain degrees in Classical Civilisation/Modernism/European History/Religious Studies before even attempting this novel.

I’ll start tomorrow.

Pages read: None. Pages remaining: 933

Day 2

OK, possibly I overreacted. I think maybe I knew too much in advance. In the end, I was amazed I could make it to the end of a single sentence. But so far Ulysses is beautiful yet also sordid, and very readable. I’m glad I’ve got the reading companion though, as there was complex word play around the word ‘melon’ that I definitely wouldn’t have picked up on my own.

Pages read: 140 Pages remaining: 793

Day 3

For such a learned, intellectual novel, Ulysses also manages to be emotionally affecting. Now I’m just under a quarter of the way through I’m finding Leopold Bloom very moving. There’s something pathetic about him, and isolated and sad, even among the crowds of Dublin.

“I was happier then. Or was that I? Or am I now I? Twentyeight I was. She twentythree. When we left Lombard street west something changed. Could never like it again after Rudy. Can’t bring back time. Like holding water in your hand. Would you go back to then? Just beginning then. Would you? Are you not happy in your home you poor little naughty boy? Wants to sew on buttons for me. I must answer. Write it in the library.

Grafton street gay with housed awnings lured his senses. Muslin prints, silkdames and dowagers, jingle of harnesses, hoofthuds lowringing in the baking causeway. Thick feet that woman has in the white stockings. Hope the rain mucks them up on her.”

Pages read: 218 Pages remaining: 715

Day 4

Fair to say my pace has slackened off today. I woke up with the book on my face, which upon removal revealed two hungry cats giving me the death stare.

Pages read: 250 Pages remaining: 683

Days 5, 6, 7

I’m sure a more attentive reader would get a lot more out of Ulysses, but as an inattentive reader I’m still really enjoying it. I especially like the section which the companion tells me corresponds with The Wandering Rocks in Homer. It’s 19 sections where, by following many characters for a short time, Joyce creates the hustle and bustle of the afternoon of 16 June 1904 in Dublin. He does this as much through the inner lives of his characters and their interactions with one another, as with description. Having said that, here are some descriptions which caught me:

“Two carfuls of tourists passed slowly, their women sitting fore, gripping the handrests. Palefaces. Men’s arms frankly round their stunted forms. They looked from Trinity to the blind columned porch of the bank of Ireland where pigeons roocoocooed.”

“Stephen Dedalus watched through the webbed window the lapidary’s fingers prove a timedulled chain. Dust webbed the window and the showtrays. Dust darkened the toiling fingers with their vulture nails. Dust slept on dull coils of bronze and silver, lozenges of cinnabar, on rubies, leprous and winedark stones.

Born all in the dark wormy earth, cold specks of fire, evil, lights shining in the darkness. Where fallen archangels flung the stars of their brows. Muddy swinesnouts, hands, root and root, gripe and wrest them.”

“Moored under the trees of Charleville Mall Father Conmee saw a turfbarge, a towhorse with pendent head, a bargeman with a hat of dirty straw seated amidships, smoking and staring at a branch of poplar above him. It was idyllic: and Father Conmee reflected on the providence of the Creator who had made turf to be in bogs whence men might dig it out and bring it to town and hamlet to make fires in the houses of poor people.”

I’m very grateful for the companion guide. I’m reading part of Ulysses then the corresponding section in the guide, and this isn’t nearly as tedious as I anticipated. It reassures me that I’m picking up a lot, and it’s highlighting the things I didn’t have hope of recognising.

Among all this learning, my most significant take away is: I’m going to start using the phrase “I beg your parsnips.”

Pages read: 403 Pages remaining: 530

Day 8, 9, 10

More than 100 pages of very unpleasant scenes, filled with boorish, racist, drunk men. An effective contrast to Bloom’s sober gentleness and moderation, (although also some questionable voyeurism from him) but I was very glad to leave it behind.

I wasn’t keen on the following section set out like a play either, and Bloom and Stephen’s hallucinations weren’t the most pleasant reading.

It’s hot, my hayfever is terrible, I’m sleep deprived and grumpy so not the best reader right now. Don’t listen to me.

Pages read: 704 Pages remaining: 229

Days 11, 12

Thank goodness – back on a much more straightforward narrative (or as near to one as you get with Joyce) and I’m enjoying Ulysses again. (I don’t normally mind experimental narratives so I’m blaming my hayfever brain.) Lovely scenes between Bloom and Dedalus.

“Literally astounded at this piece of intelligence Bloom reflected. Though they didn’t see eye to eye in everything a certain analogy there somehow was as if both their minds were travelling, so to speak, in the one train of thought.”

Which is then followed by 50-odd pages of (surprisingly explicit, even by today’s standards) almost punctuation-free stream of consciousness – a brave choice to end and a masterstroke.

“…I dont like books with a Molly in them like that one he brought me about the one from Flanders a whore always shoplifting anything she could cloth and stuff and yards of it O this blanket is too heavy on me thats better I havent even one decent nightdress this thing gets all rolled under me…”

Pages read: 933 Pages remaining: zero!

So that’s me all done! And one of the Big Scary Tomes ticked off my Le Monde’s 100 Books of the Century Reading Challenge. While it doesn’t yet occupy a special place in my heart like Dubliners, I still got so much from Ulysses. It’s such an achievement to be simultaneously so epic and so determinedly everyday. I would definitely read it again, and I’d love to go to the Bloomsday events in Dublin, which I’m sure would mean I’d enjoy a re-read even more.

To end, an opportunity to indulge myself with one of the loves of my life, because here Kate Bush is singing Molly Bloom’s soliloquy:

P.S Virginia Woolf did modify her view of Ulysses at a later date: “very much more impressive than I judged. Still I think there is virtue & some lasting truth in first impressions; so I don’t cancell mine. I must read some of the chapters again. Probably the final beauty of writing is never felt by contemporaries”