Unlike Groucho Marx, I quite like television. I say this in the full acknowledgement that at least 99% of it is shocking in its lack of aspiration towards anything other than cheaply-made sensationalist drivel. And (unsurprisingly) it will never be as rewarding to me as reading is. But some of the programmes of recent years have just been astonishing. I’m careful how I use TV, which essentially means I never channel surf to sit mindlessly in front of America’s Next Top Gypsy Teenage Mom Hoarder Bounty Hunter Bride’s Got Talent or whatever else the channels are filling their many hours with repeats of. I choose what I’m going to watch, and then my addictive personality traits emerge as I stack up hour upon hour to watch in a big binge.

This is why I’ve only just started on Mad Men Season 6. But aside from my unhealthy habits, there was another reason why I stacked up the episodes. Fear. I was so worried it wouldn’t live up to itself. Surely, I thought, they’re due to screw it up? They’ll take this piece of TV perfection and turn it into yet another series that lost its way and sends fans apoplectic with grief at the betrayal? I needn’t have worried. A few minutes in to the first episode, there was a moment so completely perfect I nearly wept with relief at the beauty of it all. (For those of you who haven’t sold your soul to Rupert Murdoch in the name of timely programming, and therefore haven’t seen season 6 yet, don’t worry, this isn’t a spoiler). Here it is, the moment: Don Draper is on the beach in Hawaii reading Dante’s Inferno. That’s it. Damn, Matthew Weiner is a bona fide genius. Everything you need to know about a character distilled into one perfect moment. Don Draper, living the life everyone wants: gorgeous and successful, beautiful loving wife sipping cocktails next to him, relaxing on a beach in luxury, reading about the nine circles of Hell. I could’ve kissed the screen. If I wasn’t such an appalling housekeeper & so my TV covered in dust, I would have.

And then this got me thinking about other moments in TV where books are used as a visual clue to as to the reader’s personality. There’s the time in The Wire where McNulty (police officer) goes to Stringer Bell’s (drug lord’s)apartment, picks up a copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and is so wrong-footed by it he wonders aloud “Who the fuck was I chasing?” But often it’s unspoken, and funny: Marcus, the scarily shark-eyed ten- year- old in Spy, reading The Slap (Christos Tsiolkas) or Machiavelli’s The Prince; Gromit’s many punning titles of great novels (my favourite: Crime and Punishment by Fido Dogstoyevsky). It’s a great opportunity to flesh out a character (even a plasticine dog) without using any dialogue, in a matter of seconds. A wordless conversation between the programme makers and the viewer. So in celebration of such moments, here are two TV characters and the books I’d like to see them read (and proof, if proof were needed, that Matthew Weiner is not lying awake at night worrying that I’m about to emerge as a rival TV-producer-of-substantial-genius)…

Firstly, in celebration of the series return via Netflix, Gob from Arrested Development, for whom I recommend The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan (1989, my copy 1996, Minerva). The uninitiated can view some of Gob’s moments here:

Gob is a lunatic, obsessed with stage magic but woefully inept at its execution, a wannabe alpha male who will never lead the pack, despised by his mother and barely tolerated by the rest of his family. And he travels everywhere by Segway. I decided on The Joy Luck Club because I feel Gob could benefit from some positive female energy in his life, and this tale of two generations of mothers and daughters will immerse him in oestrogen-fuelled drama. It will also show him the power of unconditional love of parents for their children, something entirely lacking in his own life. The club of the title is a group of Chinese immigrant women who are living in San Francisco, and who get together to play mah jong. At the start of the novel one of the women, Suyuan, has died, and her daughter, Jing-Mei/June has been asked to take her place. The novel is divided into four sections as the three remaining mothers and each of the four daughters tells their story. The tales explore the experience of the women back in China, and their daughters’ experiences as the first generation growing up in San Francisco. The communication difficulties across the generations are contextualised within an Asian-American experience, but are really universal:

“For all these years I kept my mouth closed so selfish desires would not fall out. And because I remained quiet for so long now my daughter does not hear me. She sits by her fancy swimming pool and hears only her Sony Walkman, her cordless phone, her big, important husband asking her why they have charcoal and no lighter fluid….I did not lose myself all at once. I rubbed out my face over the years washing away my pain, the same way carvings on stone are worn down by water.” (Ying-Ying St.Clair)

“During our brief tour of the house, she’s already found the flaws. She says the slant of the floor makes her feel as if she is “running down”. She thinks the guest room where she will be staying – which is really a former hayloft shaped by a sloped roof – has “two lopsides”. She sees spiders in high corners and even fleas jumping up in the air – pah! pah! pah! – like little spatters of hot oil. My mother knows, underneath all the fancy details that cost so much, this house is still a barn. She can see all this. And it annoys me that all she sees are the bad parts. But then I look around and everything she said is true.” (Lena St.Clair)

The novel has been accused by some of dealing in racial stereotypes, but I think what limits this is Tan’s ability to create seven strong, original, fully drawn female characters and explore their idiosyncratic relationships. The voices of the members of The Joy Club Club are memorable and distinctive.

Secondly, Annie from Community, for whom I recommend Ham on Rye by Charles Bukowski (1982, my copy 2000, Canongate). The uninitiated can view some of Annie’s moments here:

Oh, Annie, with your relentlessly perky expression and upbeat attitude, your array of tastefully coloured angora jumpers and perfectly organised stationery. Every now and again the strain shows and the façade crumbles, and Bukowski will teach you that that is where the interesting stuff happens. Come join us on the darkside, Annie, you know you want to…… Ham on Rye is Bukowski’s most autobiographical novel, and follows his alter-ego Henry Chinaski through an abusive childhood and into an early adulthood where his main source of support and meaning is found in a bottle. After his first experience with alcohol, drinking his friend’s father’s wine, Henry sits on a bench and reflects:

“I thought, well, now I have found something. I have found something that is going to help me, for a long time to come. The park grass looked greener, the park benches looked better and the flowers were trying harder.”

The only other positive experience Henry has in a childhood filled with violence and deprivation is when a teacher praises his creativity and reads aloud an essay he has written:

“Everybody was listening. My words filled the room, from blackboard to blackboard, they hit the ceiling and bounced off, they covered Mrs Fretag’s shoes and piled up on the floor… I drank in my words like a thirsty man. I even began to believe some of them[…]So that’s what they wanted: lies. Beautiful lies. That’s what they needed. People were fools.”

Bukowski is a legend of the beat generation and his reputation for hard-living precedes him. In some ways this is unfortunate, as it suggests a reputation built on image rather than skill. But he’s a really beautiful writer who Capote could never accuse of typing, not writing. For all you fellow bibliophiles out there, here is what happens when Henry discovers the joys of the library:

“It was a joy. Words weren’t dull, words were things that could make your mind hum. If you read them and let yourself feel the magic, you could live without pain, with hope, no matter what happened to you.”

Gorgeous. Moments like that shine out like beacons amongst the violence and bleakness of Henry’s existence; Ham on Rye is a fantastic reminder of why we read.

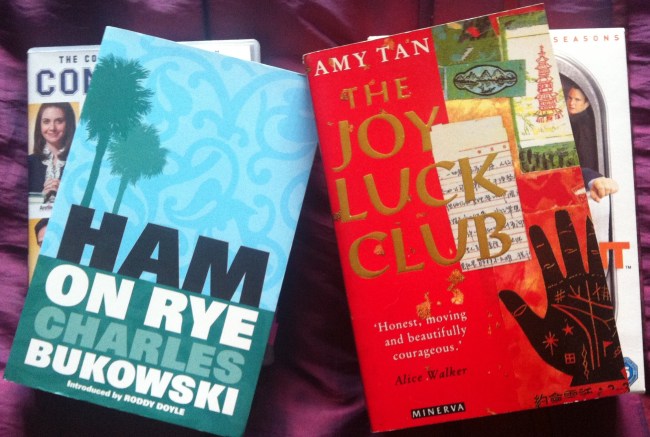

Here are Gob and Annie with their books: