This is the fourth of my planned daily posts for the wonderful 1937 Club, running all week and hosted by Kaggsy at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Simon at Stuck in a Book.

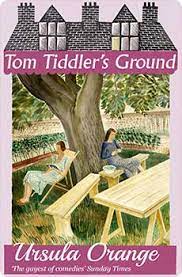

Today I’m looking at the fifth of Angela Thirkell’s Barchester novels, Summer Half. Although strictly speaking, Barchester only features now and again, most of the novel being set in Southbridge School and the master’s homes.

Reading Angela Thirkell can be a trepidatious experience. I really enjoy her comedy, but she can also be an unmitigated snob and racism can filter in too. Thankfully, although there were brief elements of both in this novel, they were always short-lived. There are also repeated references to hitting women thrown casually into conversation, although no suggestion it would actually occur.

Those elements aside, I was in the mood for a comic novel featuring events of no consequence, and that was exactly what I got. I really enjoyed it!

Summer Half begins with Colin Keith, the least interesting of the characters, deciding to take a job teaching the Mixed Fifth at the local public school, Southbridge. His father is keen for him to become a barrister, but Colin decides for wholly flimsy reasons to educate the young. He has no vocation for it and finds the prospect terrifying.

“He saw himself falling in love with the headmaster’s wife, nourishing unwholesome passions for fair-haired youths, carrying on feuds, intrigues, vendettas with other masters, being despised because he hated cricket, being equally despised because he didn’t know the names of birds, possibly being involved in a murder which he could never prove he hadn’t committed, certainly marrying the matron.”

None of the above happens and thankfully the Mixed Fifth decide they like him and don’t give him a hard time. The irrepressible Tony Morland from earlier Barchester novels features – now an adolescent – along with his friends Eric Swan and chameleon-loving Hacker.

“Hiding their eagerness under an air of ancient wisdom, critically kind, agreeably aloof, living private lives in the public eye, exploring every wilderness of the mind, yet concerned with a tie or scarf.”

The Masters live in school during term time, and so Colin befriends Everard Carter, a teacher of ability and dedication, who isn’t remotely sentimental about his charges but admits: “I’m wretched without them.” There is also grumpy, socially inept Philip Winter, (a communist!) engaged to Rose Birkett, the beautiful “sparrow-wit” daughter of the headmaster.

Rose is the nearest the novel has to a villain, and she isn’t really villainous. She’s just monumentally self-focussed and devoid of any capacity to comprehend anyone’s needs beyond her own. She enjoys male attention (presumably because admirers will want to please her) and continuously gets engaged:

“What significance, if any, she attached to the word engaged, no one had yet discovered, unless it meant being taken out in the cars of the successive young men to whom she became attached. Her parents very much hoped she would grow out of the habit in time, but for the present all they could do was tolerate young Mr Winter and hope for the best.”

Colin takes Everard Carter to his home over the holidays, where he promptly falls in loves with Kate Keith, Colin’s sister. Her frankly pathological obsession with darning everyone’s clothes and sewing on buttons doesn’t stop Carter from falling in love at first sight: “he saw his journey’s end”.

Lydia, Colin’s youngest sister, is quite the contrast to Kate. She is boisterous and given to fits of passion over Horace and Shakespeare, while proclaiming a future for herself of staying unmarried and breeding golden cocker spaniels. She also has no qualms about ripping her clothes, stuffing her food, and starting arguments with people she has perceived as doing wrong by those she cares about.

Needless to say, Lydia and Tony become good friends. I thought they were perfectly suited, both being characters I like and enjoy immensely in books, yet would find irritating beyond belief in real life.

We follow this privileged set through a summer of school, picnics, punting on rivers, tennis, croquet, unfounded jealousies and rivalries which are resolved amicably, and the most English of love affairs:

“If he did touch her he thought he might go mad, and as he was right at the end of the pew farthest from the door, that would have been uncomfortable for everyone.”

Summer Half is an ensemble piece where everyone bumbles along together more or less agreeably. Spiky, rude Philip is quite the reformed character by the end, and Rose remains entirely unreformed but nor is she punished.

There are some great comic set pieces, including such dramas as an overflowing bath, and the cleaning of a pond to avoid church attendance. That’s about as high as the stakes get, which was entirely what I wanted.

Summer Half is an enjoyable, escapist read with no aspirations towards being anything other than it is, as Thirkell’s disclaimer at the start would indicate: “It seems to me extremely improbable that any such school, masters, or boys could ever have existed.” Sometimes we need a break, and for me this was exactly the right novel at the right time.

To end, there are many songs about summer which I could choose, but I’ve opted for this completely bonkers video, set for reasons that are entirely unfathomable, in a boys boarding school. It’s no wonder our country’s in the state it is if this is what goes on at Eton: