I’ve finished at work now and my leaving gift was bookshop.org vouchers (to quote my colleague: “Tell me what you want so you don’t get some rubbish you’ll never use” 😀 ) which of course I started spending the same day! My first purchase was two novellas because it is #NovNov after all, hosted by hosted by Cathy and Bookish Beck.

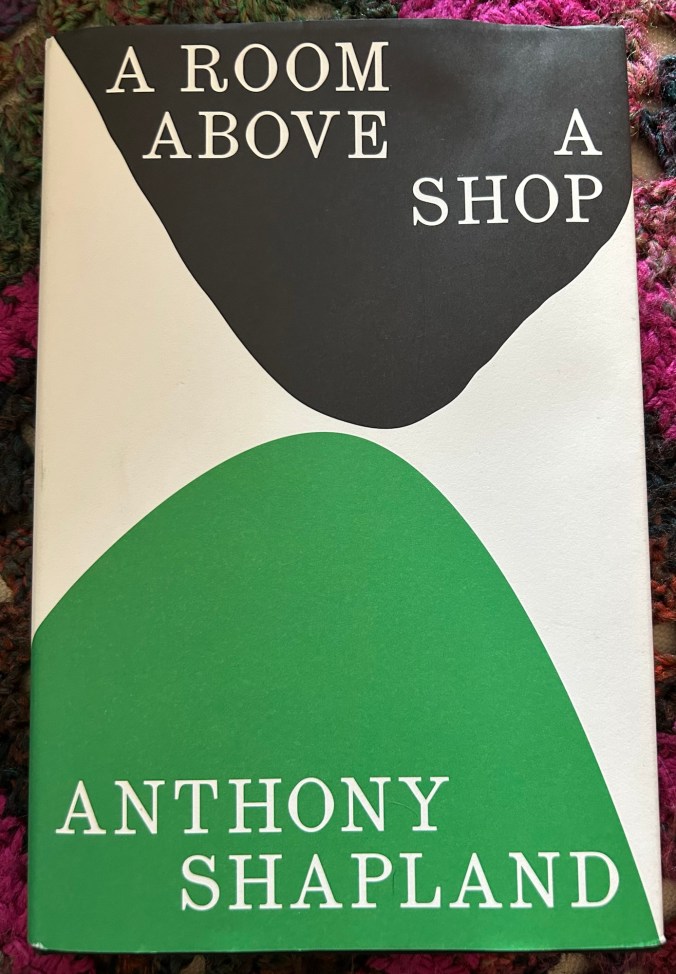

It was Susan’s review of A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland (2025) which made it a must-read for me, and my astronomical expectations were met entirely. It’s a beautifully written, carefully observed and deeply moving novel.

M has inherited a hardware shop from his father. Part of the place for years and providing a community service, everyone knows who he is without knowing him at all.

“Keeping shop hours, he is the ear of the village, the listener. They never register his life at all, upstairs in that one room.”

He meets B, somewhat younger than him, in the pub, and invites him to meet on Carn Bugail on New Year’s Eve.

“He’s not quite sure what he’s walking towards. A pulling and pushing – his instinct says go; his anxiety says stay. Either choice feels wrong. He can’t not act.”

They know it is the start of something, they know there is attraction between them, but they live in a small community, still reeling from miners’ strikes and with increasing homophobia driven by a fear of a new illness, HIV.

“Paid work is fragile, rare. Divisions still run deep; picket-angry graffiti still visible, disloyal homes shunned. Pockets are empty, borrowing and mending and patching. Everything feels temporary. Desperate.”

When B takes a job at M’s shop and moves into the spare space upstairs, little more than a cupboard but useful for appearances’ sake, they build a life together. But it is a hidden life which takes place behind closed doors, and runs beneath the performance they undertake each day as colleagues in the shop. It is both familiar and filled with tension.

“This hill is a bright map of his childhood. A play track for stunt bikes, a den, a place to be lost, to disappear with siblings. Or away from them. A place to loiter and mitch dull school days out until the bell. The place to be alone with this feeling that he’s different to the others.”

Shapland achieves something remarkable in just 145 pages, with plenty of space on the page. He crafts a fully realised portrait of two people and their relationship within a clearly evoked setting. The historical details are light touches, just enough to give a flavour of the time and certainly enough to build the pressure that M and B are living under.

His writing is incredibly precise, so although the story is short, it is not a quick read. Every single word carries its full weight to create beautiful sentences. I found myself double-checking the author bio to see if he was poet as he writes with such sparse care, but apparently not.

A Room Above a Shop is so moving. Witnessing the silences that surround M and B, the way they are unable to make the most everyday, harmless expressions of love and care towards one another, or to have their relationship acknowledged by anyone other than themselves, is quietly devastating.

“No word or deed reaches the ground from this floating platform, on this mattress, this raft, on this ocean adrift in the afternoon sun. This room lightly tethered by stairs.”

To end, a scene of coming out in a 1980s Welsh mining village from Pride, and apparently pretty accurate of the real-life person’s experience: