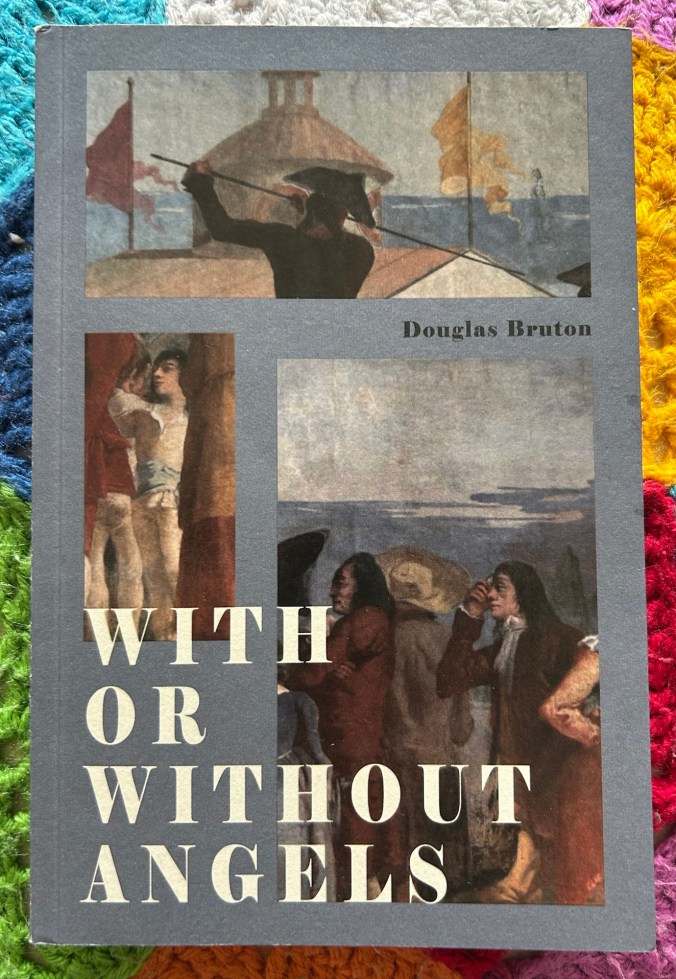

Blue Postcards – Douglas Bruton (2021) 151 pages

Earlier in the month I read With or Without Angels and I’d thought I might save Blue Postcards by the same author until the end of May, but in the end I couldn’t wait 😊Especially as Simon read this as part of his #BookADayInMay and loved it. You can read his review here.

Having now read three of Douglas Bruton’s books the word that comes up for me is tender. His writing is so gentle and subtle, entirely without sentiment but so careful in its construction and treatment of his characters. His tenderness is not a way to turn away from difficult feelings or events, but rather a way to look at them clearly and compassionately.

Blue Postcards is made up of 500 numbered paragraphs/postcards, split into five sections of 100. Almost all of them contain the word ‘blue’ (I recognised one which didn’t, there may be more). If this sounds overly contrived, it really isn’t. As you read, it flows easily and the various story threads are woven together seamlessly.

The contemporary thread involves a man who buys a blue postcard from a stall near the Eiffel Tower. The postcard is by Yves Klein, the French artist who created International Klein Blue. It is addressed to his tailor Henri, and they form the threads in the 1950s.

The narrator of the contemporary thread describes himself as ‘old’. He is aware that as he ages, his eyes perceive yellow and blue differently:

“31. Sometimes I wonder if going back to Nice I would find the sky so blue or if the blue that I found there back in 1981 had something to do with being young or something to do with memory.”

He begins a tentative relationship with Michelle, who sold him the card. Or perhaps not; he is an unreliable narrator and a theme of the book is truth, lies, fiction, and the fallibility of memory.

Henri the tailor sews blue Tekhelet threads secretly into all his suits, to bring his patrons luck.

“109. […] When I am talking about Henri I hope it is understood that we are in his time and not really in our time. If this was a film we might see Henri through a blue filter to show that his time is different.”

Yves Klein is building international success and needs a suit to look the part:

“184. Henri stands in front of the mirror next to Yves Klein in his tacked and pinned-together new suit. ‘You have to imagine it finished and pressed as sharp as knives and not a loose thread anywhere to be seen.’ Henri holds onto the sleeve of the jacket and his blue dream is briefly real.”

The postcards move back and for the between the timelines but this is never confusing or disorienting. There is a reflective, almost melancholic (blue?) tone running through both. They explore the transitory; how our experiences are constantly shifting as we rewrite the past from a changing present and our changing understanding.

The tone is lightened by the Yves Klein strand; his self-promotion and blatant lies therein are audacious, and even breathtaking with his Leap Into the Void.

There is also tragedy that we know exists in Henri’s past. A Jewish man in 1950s France is going to have unspeakable recent memories. The theme of grief runs across the timelines, both for those who have died and for what can never be regained.

I’ve not done any justice to this novella at all. It is so rich in themes and style, and yet so approachable and readable. I can only urge you to read it for yourself!

“267. I do not think a stone can be said to belong to a person. I tell her about the stone and how I picked it up out of a river and it was blue until it dried and then it was only blue in possibility. I tell her that I like that most especially, that blue can be something that adheres in a thing and at the same time can be something hidden. I do not tell her that I think love is something the same.”

To end, the author reading from his work: