Happy Easter! For those of you who don’t celebrate this festival, I hope you’re enjoying the long weekend (and possibly an abundance of chocolate).

(Image from: http://www.sproutcontent.com/ )

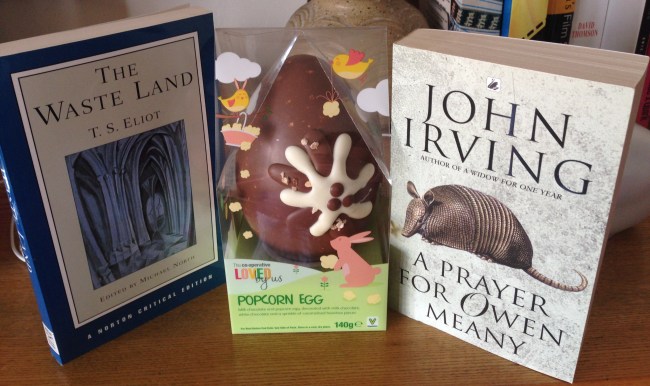

For a theme for this post I was thinking about Easter, about sacrifice and redemption, and also about Spring, the season of renewal and regeneration that it coincides with. I’ve opted for a novel with a self-sacrificing main character, and a poem that starts in April. They’re both quite odd texts: here’s to a weird Bank Holiday!

Firstly, A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving (1989, Black Swan). Irving is an enormously popular author and Owen Meany is one of his most-loved protagonists: a boy “with a wrecked voice” who is so tiny people can’t resist picking him up, his skin “the colour of a gravestone; the light was both absorbed and reflected by his skin, as with a pearl, so that he appeared translucent at times”. The story is narrated by his best friend Johnny Wheelwright, who is trying to come to terms with the role Owen has played in his life. When they are 11, Owen hits a foul ball that kills Johnny’s mother immediately. The boys reconcile by swopping their most treasured possessions: “He gave me his baseball cards, but he really wanted them back, and I gave him my stuffed armadillo, which I certainly hoped he’d give back to me – all because it was impossible for us to say to each other how we really felt.”

When he returns the armadillo, Owen has taken its claws, which Johnny comes to realise is Owen’s way of telling him: “GOD HAS TAKEN YOUR MOTHER. MY HANDS WERE THE INSTRUMENT. GOD HAS TAKEN MY HANDS. I AM GOD’S INSTRUMENT.” Owen’s speech is always in capitals to represent his bizarre voice, and as a device it really works, marking him out not only against the other characters but also in the book itself – you can flick through and find Owen immediately. So, Owen is already unusual, but is even more extraordinary than people realise. He thinks he is God’s instrument, and certainly Johnny agrees: “I now believe that Owen Meany always knew; he knew everything.” The events of their lives mean not only that “Owen Meany rescued me” and gave Johnny Christian faith, but that Owen’s absolute conviction in a greater scheme of things and his capacity for self-sacrifice are tested to the extreme. It’s so hard to say any more without giving away spoilers, but I urge you to read it. A Prayer for Owen Meany is a novel as truly original as its protagonist, funny and sad, elegiac and uplifting.

Secondly, The Waste Land by TS Eliot, a hugely famous and notoriously difficult poem. For what it’s worth, I would say don’t let the reputation it put you off. If you fancy giving it a go, read it and let the “heap of broken images” wash over you, see what it brings. You can always re-read using the footnotes (which will be copious – and Eliot’s own notes add more confusion rather than explication) to translate the Latin, Greek etc and find out about the plethora of allusions. The poem begins:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

These lines are an allusion to the start of The Canterbury Tales:

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes…

As you can see, Eliot takes the same premise but where Chaucer sees pastoral idyll (admittedly evoked a little ironically) Eliot sees something bleaker, death amongst the renewal, cruelty amongst the desire. The Waste Land is an odd, unsettling poem; its original title was going to be He Do the Police in Different Voices (a line from Our Mutual Friend) and The Waste Land is certainly a cacophony of voices, evoking different times, places and stories. As an embittered commuter who used to cross London Bridge every day, the following passage always sticks in my mind:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

The Waste Land does this frequently, takes images that almost seem commonplace, like commuters walking over a bridge, and then undermines it, in this instance when you realise they are all ghosts, their movement seemingly without purpose. The Waste Land is a poem that defies easy explanation and raises far more questions than it answers. It can be a frustrating read, but also a hugely rewarding one that benefits from multiple readings.

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

For a very interesting discussion on The Waste Land and how we read, head over to Necromancy Never Pays.

I feel like I should picture the books with an egg as odd and unsettling as the books themselves, a dinosaur egg or something. (Or an armadillo egg? But I’m feeling too lazy to make them, it is a Bank Holiday after all…) So here they are instead with a reassuringly chocolatey easter egg, a present from my brother: