This is the first of what I hope will be a few posts for Cathy’s annual Reading Ireland Month aka The Begorrathon.

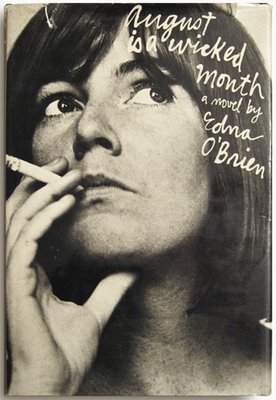

I really enjoyed August is a Wicked Month by Edna O’Brien when I read it a few years ago, and resolved to read The Country Girls trilogy. Admittedly it’s taken me a while but I have finally picked up the first in the trilogy, and O’Brien’s debut novel, The Country Girls (1960). Cathy and Kim are also hosting A Year with Edna O’Brien throughout 2025 so I’m joining in with that too 🙂

The girls of the title are Cait and Baba, growing up in 1950s rural Ireland, and the tale is told by Cait. Once again, I found O’Brien so intensely readable. She is great at small details that illuminate so much, without overwriting:

“Slowly I slid onto the floor and the linoleum was cold on the soles of my feet. My toes curled up instinctively. I owned slippers but Mama made me save them for when I was visiting my aunts and cousins; and we had rugs but they were rolled up and kept in drawers until visitors came in the summer-time from Dublin.”

Cait lives with her parents and man-of-all-work Hickey, on their farm which is hanging on by a thread, not helped by her father going on frequent alcohol benders. Her mother is loving but they all live in fear of her father’s return and the violence he brings.

“Her right shoulder sloped more than her left from carrying buckets. She was dragged down from heavy work, working to keep the place going, and at night-time making lampshades and fire-screens to make the house prettier.”

Baba’s family is better off financially, but they have their own sadnesses including her mother also self-medicating with alcohol. Baba can be a spiteful bully, but Cait experiences a growing awareness of how much Baba needs her too.

“Coy, pretty, malicious Baba was my friend and the person whom I feared most after my father.”

Village life is not idyllic in O’Brien’s world. There is a lot of poverty, there is violence, deep unhappiness and gossip. The girls are subject to the sexual attentions of much older men, even as they are at school.

Cait is academic and wins a scholarship to a convent school. Baba’s family pay for her to have a place too, and so the girls leave their village for the first time.

Baba despises the school with her whole being:

“Jesus, tis hell. I won’t stick it for a week. I’ll drink Lysol or any damn thing to get out of here. I’d rather be a Protestant.”

O’Brien brilliantly creates the cold, the disgusting food, the boredom and the oppressive rules laid down by the nuns.

“The whole dormitory was crying. You could hear the sobbing and choking under the covers. Smothered crying.

The head of my bed backed onto the head of another girl’s bed; and in the dark a hand came through the rungs and put a bun on my pillow.”

Eventually Baba engineers a way for her and Cait to leave, which to my twenty-first century eyes was very funny, but perhaps contributed to the banning of the book in Ireland and the burning of it by a priest when it was first published.

So in disgrace, the girls make their way to Dublin and all the seductions of city life, which Baba in particular is keen to embrace.

“Forever more I would be restless for crowds and lights and noise.”

The scandal The Country Girls created in 1960 seems very dated now. The only part I found concerning was a relationship that Cait begins with Mr Gentleman, a married man much older than she is, when she is still at school. This continues throughout the novel; it remains unconsummated but is wholly inappropriate and what we would now call grooming.

Apparently O’Brien wrote this in three weeks which is just extraordinary. Her evocations of environment and people, her ear for dialogue and her fluidity of style are all so well observed.

The novel ends on an anti-climax which initially I found an odd decision, but reflecting on it I think it is one of its strengths. It emphasises O’Brien’s choice to write about the realities of life for young women at that time, the life she knew. It insists on its truth, more than overly dramatic scenes, to engage the reader.

I’m looking forward to catching up with Cait and Baba in The Lonely Girl – hopefully it won’t take me another two years!

“I was not sorry to be leaving the old village. It was dead and tired and old and crumbling and falling down. The shops needed paint and there seemed to be fewer geraniums in the upstairs windows than there had been when I was a child.”

To end, a great interview with the author from the time of her memoir being published. She discusses The Country Girls around 11 minutes in: