Although I read a lot of golden age detective fiction as it is my go-to comfort read, I rarely blog on it. I’m making an exception this week though, as The Crime at Black Dudley, the first Albert Campion mystery by Margery Allingham, was published in 1929. This makes it perfect for the 1929 Club, running all week and hosted by Simon and Kaggsy.

In this first outing, Campion is not the primary detective. This role falls instead to George Abbershaw:

“He was a smallish man, chubby and solemn, with a choir-boy expression and a head of ridiculous bright-red curls which gave him a somewhat fantastic appearance.

[…]

His book on pathology, treated with special reference to fatal wounds and the means of ascertaining their probable causes, was a standard work, and in view of his many services to the police in the past his name was well known and his opinion respected at the Yard.

At the moment he was on holiday, and the unusual care which he took over his toilet suggested that he had not come down to Black Dudley solely for the sake of recuperating in the Suffolk air.

Much to his own secret surprise and perplexity, he had fallen in love.

He recognized the symptoms at once and made no attempt at self-deception, but with his usual methodical thoroughness set himself to remove the disturbing emotion by one or other of the only two methods known to mankind – disillusionment or marriage.”

So George heads to a somewhat foreboding enormous country pile, home of Wyatt Petrie, an academic, and his uncle Colonel Coombe (there always seem to be Colonels in GA mysteries don’t there? They seem to have been much more prolific then.) There is to be a party of Bright Young Things descending for the weekend.

An isolated country house, a closed circle of characters not entirely well-known to one another, what could go wrong…? Early on, George is drawn to a wall display:

“Yet it was the actual centre-piece which commanded immediate interest. Mounted on a crimson plaque, at the point where the lance-heads made a narrow circle, was a long, fifteenth-century Italian dagger. The hilt was an exquisite piece of workmanship, beautifully chased and encrusted at the upper end with uncut jewels, but it was not this that first struck the onlooker. The blade of the Black Dudley Dagger was its most remarkable feature. Under a foot long, it was very slender and exquisitely graceful, fashioned from the steel that had in it a curious greenish tinge which lent the whole weapon an unmistakably sinister appearance. It seemed to shine out of the dark background like a living and malignant thing.”

How on earth will the murder take place? What weapon will possibly be used? That’s right, Colonel Coombe is poisoned. Only kidding, of course he’s stabbed with the heavily foreshadowed Black Dudley Dagger.

However, that is not the only dampener on the party. Two men, sinister associates of the deceased, proclaim that no-one is allowed to leave until a missing item is returned to them. They succeed in convincing everyone of their seriousness through direct and effective means. (One of them is German and my heart sank a bit, anticipating caricatured xenophobic villainy, but thankfully although there is some it’s not extensive, and it soon becomes apparent that *small spoiler* he is not the true villain).

What will George do? Can he unmask the murderer? Can he protect his beloved Meggie long enough to propose? Well, among the party is one Albert Campion. George finds him foolish and irritating. Silly George! It’s obvious to the reader that there is More To Albert Than Meets The Eye…

“Everybody looked at Mr Campion. He was leaning up against the balustrade, his fair hair hanging over his eyes, and for the first time it dawned upon Abbershaw that he was fully dressed, and not, as might have been expected, in the dinner-jacket he had worn on the previous evening.

His explanation was characteristic.

‘Most extraordinary,’ he said, in his slightly high-pitched voice. ‘The fellow set on me. Picked me up and started doing exercises with me as if I were a dumb-bell. I thought it was one of you fellows joking at first, but when he began to jump on me it percolated through that I was being massacred. Butchered to make a butler’s beano, in fact.’

He paused and smiled fatuously.”

The main flaw of The Crime at Black Dudley is that mysterious, capable, comic Campion is so clearly the hero that the story feels a bit unbalanced and lacking when he’s not around. He dominates until he suddenly doesn’t – leaving the story before the end. George sees it through for the reader, but it makes for something of an anti-climax.

However, that quibble aside, The Crime at Black Dudley is a very enjoyable golden age mystery. As well as the tropes already mentioned, there are trapdoors, secret passageways and international criminal gangs. It’s a short fun read, and it made me keen to spend more time with perplexing Campion. As the Bright Young Things might say, (but probably never did) even if it’s not entirely the cat’s pyjamas it is still a crashing good lark.

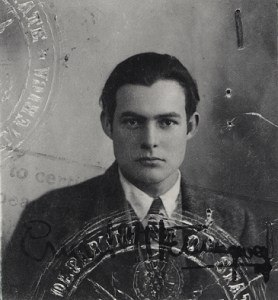

From the silly to the serious, and my usual disclaimer that I know Ernest Hemingway was a fairly terrible human. He treated women badly, he loved blood sports which is abhorrent, I have no doubt that had we ever met, Hemingway and I would have viewed each other with mutual contempt. I also know that I just adore his writing, in a way I can’t fully explain. I do like pared-back style, but there’s something indefinable in his writing that I just find so moving. A Farewell to Arms was published in 1929 and it opens:

“In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.”

If I tell you I was already inexplicably tearful by the time I reached the end of that passage you know you’re not going to get a coherent or balanced review of this book in any way 😀

The novel follows the story of Frederic Henry, an American volunteer paramedic in Italy during the First World War, and his relationship with Catherine Barkley, an English nurse. Initially I found their behaviour rather silly, but then I had to remind myself that they were very young, and living through traumatic circumstances.

“I went out the door and suddenly I felt lonely and empty. I had treated seeing Catherine very lightly, I had gotten somewhat drunk and had nearly forgotten to come but when I could not see her there I was feeling lonely and hollow.”

“‘I’ll say just what you wish and I’ll do what you wish and then you will never want any other girls, will you?’ She looked at me very happily. ‘I’ll do what you want and say what you want and then I’ll be a great success, won’t I?’”

No Catherine, that’s a truly terrible idea. Familiarise yourself with feminist theory and pull yourself together!

I thought Hemingway’s iceberg style of writing, not spelling everything out and trusting the reader to fill in gaps, worked extremely well throughout. Being so matter-of-fact about war, death and injury drove home its seriousness rather than treating it lightly. It meant that nothing was made easier by a more descriptive or metaphorical style. Here Henry is wounded badly (skip the next quote if you’re at all squeamish!):

“I sat up straight and as I did so something inside my head moved like the weights on a doll’s eyes and it hit me inside behind my eyeballs. My legs felt warm and wet and my shoes were wet and warm inside. I knew that I was hit and leaned over and put my hand on my knee. My knee wasn’t there. My hand went in and my knee was down on my shin. I wiped my hand on my shirt and another floating light came very slowly down and I looked at my leg and was very afraid.”

A Farewell to Arms is not relentlessly bleak though. There are touches of humour between Henry and his friends, or in Henry’s observations of his medical care:

“I have noticed that doctors who fail in the practice of medicine have a tendency to seek one another’s company and aid in consultation. A doctor who cannot take out your appendix properly will recommend to you a doctor who will be unable to remove your tonsils with success. These were three such doctors.”

It’s also not bitter. Henry becomes disillusioned with the war but again, the iceberg style works well in presenting the hopelessness and destruction of ideals, without being cynical or maudlin, such as Henry’s conversation with his friend who is a priest:

‘I had hoped for something.’

‘Defeat?’

‘No. Something more.’

‘There isn’t anything more. Except victory. It may be worse.’

‘I hoped for a long time for victory.’

‘Me too.’

‘Now I don’t know.’

‘It has to be one or the other.’

‘I don’t believe in victory anymore.’

‘I don’t. But I don’t believe in defeat. Though it may be better.’

‘What do you believe in?’

‘In sleep,’ I said. He stood up.

It occurred to me towards the end of the novel, when Henry uses a racial slur, that until that point I hadn’t really considered whether I liked any of characters. At that point I reflected that I didn’t much. Catherine is somewhat underwritten, the first-person narrative reflecting Henry’s youthful egotism in love, and Henry himself wasn’t particularly easy to warm to. But actually this was irrelevant. Hemingway wasn’t asking the reader to like or not like his characters. He was presenting them as they were, as flawed humans caught up in violence and destruction, and pointing out utter futility of it all.

“I did not say anything. I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious and sacrifice and the expression in vain. We had heard them, sometimes standing in the rain almost out of earshot, so that only the shouted words came through, and had read them, on proclamations that were slapped up by billposters over other proclamations, now for a long time, and I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it. There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity.”

To end, the trailer for the 1932 film adaptation starring Gary Cooper: