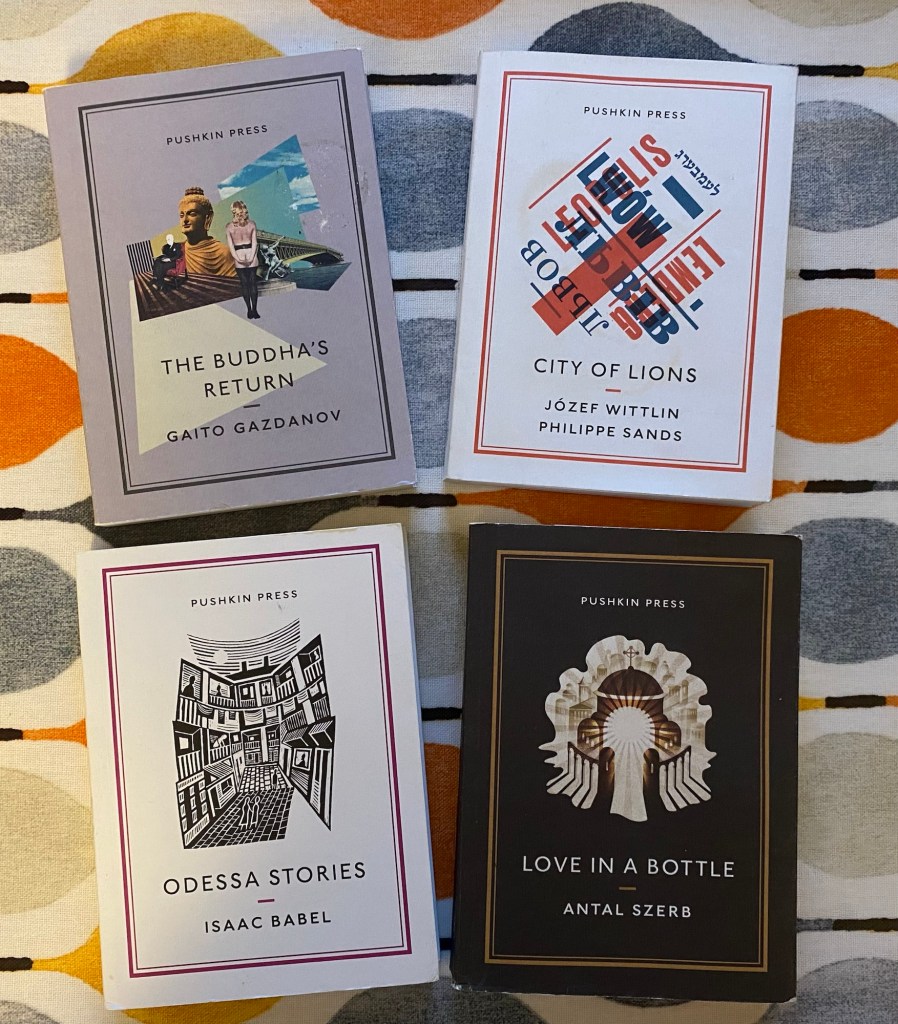

This week I’m focussing on Pushkin Press as part of Kaggsy and Lizzy’s #ReadIndies event to finally read four books that have long been in the TBR. Today it is a book of two essays, City of Lions by Józef Wittlin and Philippe Sands.

Pushkin Press’ website describes the volume: “Lviv, Lwów, Lvov, Lemberg. Known by a variety of names, the City of Lions is now in western Ukraine. Situated in different countries during its history, it is a city located along the fault-lines of Europe’s history. City of Lions presents two essays, written more than half a century apart – but united by one city.”

The book comes with maps of Lwów and Lviv within the French flaps and photographs throughout which are both useful and illustrative, making a really lovely edition. It also forms another stop on my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge.

Józef Wittlin was a poet and novelist and his essay My Lwów (1946, transl. Antonia Lloyd-Jones 2016) beautifully evokes his longing for a city he knows has gone forever, with his writing full of nostalgia and loss.

Wittlin is completely aware of his skewed view of the city, having left in 1922 and writing his essay sat in New York so many years later:

“Nostalgia even likes to falsify flavours too, telling us to taste nothing but the sweetness of Lwów today. But I know people for whom Lwów was a cup of gall.”

Yet still he longs for city of his past.

“Alright, so Lwów hasn’t got a decent river, or a legend. What would it need a river for? The urban planners and tourists say that if Lwów were graced with a river, it would be a second Florence. In my view Lwów has more greenery than Florence, though less of the Renaissance. Moreover, it resembles Rome…”

But as Wittlin evokes the cityscape, its smells, food and people with great artistry and passion, world events – recent at the time of his writing – do filter through. In his evocation of a culturally mixed European city in the early twentieth century, he would have been aware that the Jewish population which had made up around a third of Lwów’s inhabitants had been almost entirely wiped out.

“It is not Lwów that we yearn after all these years apart, but for ourselves in Lwów.”

Philippe Sands essay My Lviv (2016) is written in conversation with My Lwów and views the city through the eyes of someone who never lived there, but whose family history – and the reason they had to leave – is firmly rooted there.

“I could have chosen to turn away from the stories stuffed into the cracks of each building, or what was hidden behind freshly plastered walls. I could have averted my gaze, but I didn’t want to. Observing with care was part of the reason for being there, seeking out what was left, traces of what came before.”

Sands essay is deeply personal as he revisits his grandfather Leon’s home city. It is an experience he feels deep in his bones:

“I understood it to be part of my hinterland, one that was buried deep because Leon would never speak of that past. His long silence hid the wounds of a family that was left and then lost, but from the moment I set foot in the place it felt familiar, a part of me, a place I had missed and where I felt comfortable.”

At the same time, Sands is visiting with broader knowledge of devastation wreaked by the Holocaust, and he sees these layers within Lviv, even when they aren’t overtly commemorated:

“The first time I stood in the courtyard behind the school, in the autumn of 2012, I had no idea what that yard had been used for. Now armed with that knowledge, that this vast and empty place was a gathering point for thousands of final journeys […] it was a place of terrible silences, the expression of a conscious desire not to remember.”

I found City of Lions a deeply moving read. It is an elegy for a lost time, a eulogy for those lost, and a stark reminder that history is lived and died through by ordinary people. Cities grow and change, but they build upon and contain all that has gone before. It is all there if we take the time and care to look.

At the same time, what these two very different evocations of the same city demonstrate so well is that we experience our surroundings through ourselves. Wittlin and Sands are writing as much about themselves as they are about the city, but the essays are no less fascinating for that.