Today is May Day, and I was thinking about the traditions of this time: celebration, revelry, pastoral fertility. Please note I said thinking about, not participating in. Confession time, reader: even though I’m in Oxford I didn’t want to do an all-night pub crawl/ball or get up at ridiculous o’clock to go to Magdalen Bridge for May Morning. I lay in bed, and because Oxford is so quiet I could hear the choir and bells anyway, and it was beautiful. Better warm in bed than in an inebriated crowd, I told myself. Before I seem too virtuous, I should tell you that I’m really just lazy, because an hour or so later I got up for a champagne breakfast. If this post seems even more waffly and incoherent than usual, you know why.

So, the traditions of May Day, and choosing books for this post made me think about the carnivalesque in novels. Mikhail Bakhtin said that the carnivalesque (this is a shockingly rough paraphrase) is a time when social hierarchies are overthrown in energetic riot: as norms are disregarded, reversed and subverted, anything can happen. Sounds like the spirit of May Day to me. Hence, for this post I’ve picked two novels that are carnivalesque/subversive in some way.

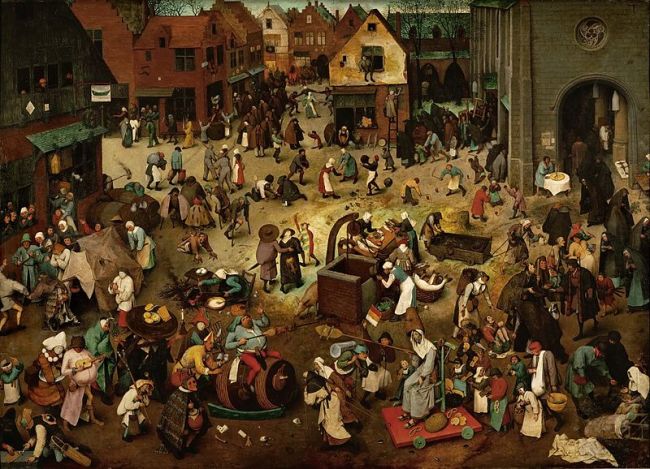

The Battle Between Carnival and Lent – Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1599 (Image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pieter_Bruegel_d._%C3%84._066.jpg )

My first choice is Nights at the Circus by Angela Carter (1984, Chatto & Windus). The minute I started to think about carnivalesque, this is what sprang to mind. I thought the summary on the dust jacket was spot-on, so here it is:

“Fevvers: the toast of Europe’s capitals, courted by princes, painted by Toulouse Lautrec, the greatest aerialiste of her time. Fevvers: somersaulting lazily through the air, hovering in the moment between the nineteenth century and the twentieth, between old dreams and new beginnings, born up by the spread of wings that can’t be real! Or- can they? Fevvers: the Cockney Venus, six foot two in her stockings, the coarsely lively and lovely heroine…Obsessed with Fevvers, constantly bamboozled by the anarchist sorcery of her dresser and confidante, Lizzie, the dashing young journalist Jack Walser stumbles into a journey which takes him from London to Siberia via legendary St Petersburg and out of his male certainties, into a transforming world of danger and joy, the world of Colonel Kearney’s circus…Featuring a cast of thousands, including : the clown’s requiem, the tigers’ waltz, the educated apes, the bashful brigands, the structuralist wizard. Not forgetting Sybil, the Mystic Pig.”

Just brilliant. I’ve said before that there’s no-one like Angela Carter, and Nights at the Circus is her writing at her very best. Fevvers voice leaps of the page at you in the first paragraph:

“Lor’ love you sir!” Fevvers sang out in a voice that clanged like dustbin lids. “As to my place of birth, why, I first saw the light of day right here in smoky old London, didn’t I! Not billed the ‘Cockney Venus’ for nothing…Hatched out of a bloody great egg while Bow Bells rang, as ever is!”

If that all sounds a bit “cor-blimey-luvvaduck-rent-a-cockney”, don’t worry. With Angela Carter you are never in the land of the stereotype, but in an exuberant world of characters the like of which you will never have met before, or since. She is master of the original and evocative image (“like dustbin lids”) and while her work is carnivalesque and destabilising, it’s also great fun. The circus is Carter’s world, which means anything can happen. But beneath all the sparkle and pizzazz, she creates a world of substance. Buffo the clown reflects:

“We are the whores of mirth, for, like a whore, we know what we are; we know we are mere hirelings hard at work yet those who hire us see us as beings perpetually at play. Our work is their pleasure and so they think our work must be our pleasure, too, so there is always and abyss between their notion of our work as play, and ours, of their leisure as our labour.”

Carter uses magic realism to explore how we construct reality, and how easily it can be deconstructed. Where better to do that than the circus? She plays with notions of gender and sexuality, challenging the idea that they are fixed entities, and explores how identity can be constantly created and recreated. Jack falls in love with Fevvers, unsure of who, or what, it is he loves: if he gets behind the image of the Cockney Venus, who will be there? Is she part bird? And who will he be in response?:

“When Walser first put on his make-up, he looked in the mirror and did not recognise himself. As he contemplated the stranger peering interrogatively back at him out of the glass, he felt the beginnings of a vertiginous sense of freedom , that, during all the time he spent with the Colonel, never quite evaporated; until that last moment where they parted company and Walser’s very self, as he had known it, departed from him, he experienced the freedom that lies behind the mask, with dissimulation, the freedom to juggle with being, and, indeed, with the language which is vital to our being, that lies at the heart of burlesque.”

Angela Carter clearly had a fierce intellect and something interesting to say about how we make our worlds. But she also didn’t let that get in the way of a good story. Nights at the Circus is a fantastic read, in all the senses of the word.

Secondly, Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726, full text available online). Obviously, this novel is hugely famous (even if you haven’t read it I bet you know what physical feature distinguishes a Lilliputian). Lemuel Gulliver relates fantastical tales of his travels, and in the process Swift offers a satire on travel narratives (which were hugely popular in the eighteenth century as people travelled further and wider) and on the human condition. I chose it for this theme as it is full of inversions and reversals; Gulliver travels to Lilliput, where he is a giant, then to Brobdingnag where he is minute; to Laputa which he considers crude and unenlightened, then to the Houyhnhnms who consider him a “yahoo”. Gulliver’s Travels is episodic, so I’m just going to pick out a couple of events. Firstly, one of the most famous ones: many writers at the time were obsessed by bodily functions, and Swift is no different, though thankfully not nearly as scatological as some of his contemporaries. Here is Gulliver putting his urine to good use in Lilliput:

I was alarmed at midnight with the cries of many hundred people at my door; by which, being suddenly awaked, I was in some kind of terror….her imperial majesty’s apartment was on fire, by the carelessness of a maid of honour, who fell asleep while she was reading a romance. I got up in an instant; and orders being given to clear the way before me, and it being likewise a moonshine night, I made a shift to get to the palace without trampling on any of the people. I found they had already applied ladders to the walls of the apartment, and were well provided with buckets, but the water was at some distance. These buckets were about the size of large thimbles, and the poor people supplied me with them as fast as they could: but the flame was so violent that they did little good… this magnificent palace would have infallibly been burnt down to the ground, if, by a presence of mind unusual to me, I had not suddenly thought of an expedient. I had, the evening before, drunk plentifully of a most delicious wine called glimigrim, (the Blefuscudians call it flunec, but ours is esteemed the better sort,) which is very diuretic. By the luckiest chance in the world, I had not discharged myself of any part of it. The heat I had contracted by coming very near the flames, and by labouring to quench them, made the wine begin to operate by urine; which I voided in such a quantity, and applied so well to the proper places, that in three minutes the fire was wholly extinguished, and the rest of that noble pile, which had cost so many ages in erecting, preserved from destruction.

And just to finish, here is a bit of the more heavy-handed satire for you, when the king of Brobdingnag responds to a summary of British politics:

“He was perfectly astonished with the historical account gave him of our affairs during the last century; protesting “it was only a heap of conspiracies, rebellions, murders, massacres, revolutions, banishments, the very worst effects that avarice, faction, hypocrisy, perfidiousness, cruelty, rage, madness, hatred, envy, lust, malice, and ambition, could produce.”

I’ll leave it to you to decide if such motivations have left politics these days…

Gulliver’s Travels is a complex book, and one that is very hard to pin down: it is funny, it is sad, it can be read to children, it is baffling to adults. It shifts meaning and genre according to who is reading it: truly carnivalesque.

I was hoping to end with a clip of Bellowhead performing One May Morning Early: apt, no? But YouTube failed me. So here they are singing about a carnival romance instead: