Recently I fell subject to one of those viruses that seems never ending. Basically for about two and half weeks I was behaving like this:

(Only with much less impressive cheekbones). I wouldn’t bother mentioning it, stoic that I am, except it meant I had to turn down a last-minute ticket to see Zoe Wanamaker in Stevie, Hugh Whitemore’s play about the life of the poet Stevie Smith. I love Zoe Wanamaker and I’m sure she’d be great as the idiosyncratic Smith, so I did not take this in my stride:

(Only with much less impressive cheekbones). So to compensate for my loss, I’m going to look at two other instances where the lives of poets have been imagined, in a novel and in a play.

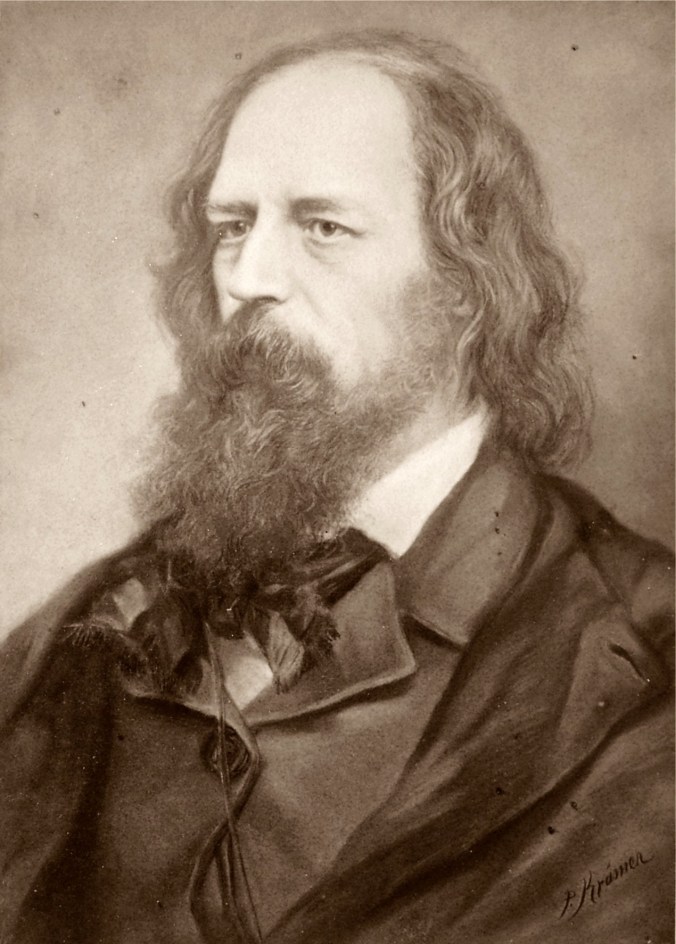

Firstly, John Clare (and to a lesser extend Alfred Lord Tennyson) as imagined by Adam Foulds in The Quickening Maze (Vintage, 2009), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2009.

John Clare suffered with poor mental health for most of his adult life, and for a time was an inpatient at High Beach Asylum in Essex. The Tennyson brothers move nearby as Septimus is being treated for depression, but thankfully this isn’t an excuse for Foulds to create conversations on the nature of poetry between the two versifiers (can you imagine? ‘What think you Clare, of this long poem of mine?’ ‘Will you permit me Alfred, to suggest In Memoriam is better name than My Friend Hallam What Died?’ Ugh. OK, so Foulds would never be that bad, but sometimes these things can be so clumsy as to become comical).

Instead Foulds looks at the lives contained within and without the asylum, and the nature of their various freedoms and restraints. Alongside the patients live the profligate Dr Allen, who has progressive ideas on treatment but lacks the focus to truly push things forward; his daughter Hannah, desperate for freedom but unsure how to get it other than by marrying; the grieving Tennyson yearning for his dead friend and for critical approval; and of course Clare, the ‘peasant poet’, determined to leave the built environment of the asylum for the forest beyond:

“As he worked in the admiral’s garden…being there, given time, the world revealed itself again in silence, coming to him. Gently it breathed around him its atmosphere: vulnerable, benign, full of secrets, his. A lost thing returning. How it waited for him in eternity and almost knew him. He’d known and sung it all his life.”

Things begin to unravel: Clare becomes progressively more deluded, the doctor veers towards bankruptcy again, Hannah harbours fantasies regarding Tennyson which amount to nothing. But The Quickening Maze is a novel of quiet, closely observed drama of domestic life (despite the asylum and famous poets), rather than enormous, declamatory moments:

“From her window, Hannah could see Charles Seymour prowling outside the grounds, swishing his stick from side to side. Boredom, a sane frustration, a continuous mild anger: Hannah thought he looked like a friend, someone whose life was as empty and miserable as her own…he raised a hand to lift his hat and found he wasn’t wearing one. He smiled and mimed instead. Hannah gazed for a moment down at his shoes and smiled also.”

Foulds is an accomplished poet himself, and this shows itself in tightly constructed prose full of startling images:

“She liked the pinch of absence, the hollow air, reminiscent of the real absence. She wanted to stay out there, to hang on her branch in the world until the cold had burned down to her bones. She could leave her scattered bones on the snow and depart like light.”

The result is a tightly plotted novel that maintains a contemplative, elegiac quality: perfect for the poets it captures.

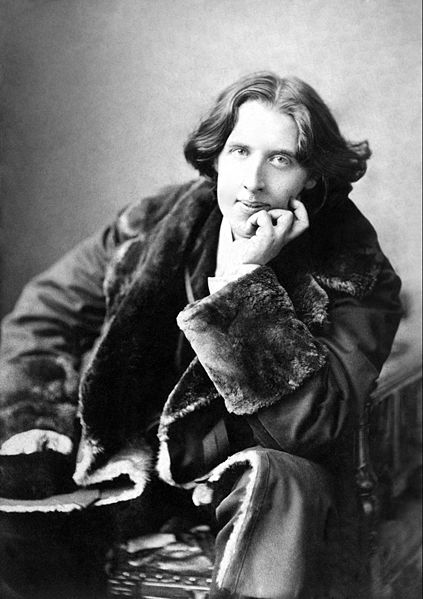

Secondly, Oscar Wilde, as imagined by David Hare in The Judas Kiss, which premiered at the Almeida in 1998.

The story of Oscar Wilde is so well-known, it can be difficult to imagine what more there is to be said on it. What Hare gives his audience is an Oscar past his prime, bruised and sad, the architect of his own downfall. The first act sees Wilde staying in London to face the court over allegations he is gay (which was illegal at the time) while his friends urge him to leave:

“Ross. Oscar, I’m afraid it’s out of the question. You simply do not have time.

Wilde. Do I not?

Ross. You are here to say your goodbyes to Bosie.

Wilde. Yes of course. But a small drink, please, Robbie, you must not deny me.

Ross. Why, no.

Wilde. And then, of course I shall get going. I shall go on the instant.

Arthur. Do you want to taste, sir?

Wilde. Pour away. Hock tastes like hock, and seltzer like seltzer. Taste is not in the bottle. It resides in one’s mood. So today no doubt hock will taste like burnt ashes. Today I will drink to my own death.”

The knowledge we have of the outcome, rather than resigning us to Wilde’s fate, actually adds to the dramatic urgency. I found myself desperately rooting for Ross, wishing Oscar would listen, that somehow the outcome would be different and he wouldn’t stay long enough to allow the courts to give him a two year sentence. But Wilde is stubborn, proud, defiant, and wonderful, as his selfish, weak lover Bosie testifies:

“You have wanted this thing. In some awful part your being, you love the idea of surrender. You think there’s some hideous glamour in letting Fate propel you down from the heights!”

But Bosie doesn’t want Wilde to leave, rather stay and fight his battles for him with his father, the Marquess of Queensbury, who is challenging Wide in court. Between his own wilfulness and Bosie’s self-interest, Wilde agrees to stay…

In the second act we are in Italy with a Wilde after he has left prison and moved abroad “grown slack and fat and his face is ravaged by deprivation and alcohol”. Bosie is enjoying himself with the local beauties, while Wilde is isolated and contemplative:

“I am shunned by you all, and my work goes unperformed, not because of the sin – never because of the sin – but because I refuse to accept the lesson of the sin.”

The Judas Kiss is a tragic play, but not in the usual sense. No-one dies, there is no physical violence, and yet we witness betrayal, destruction and loss. It’s heart-breaking, and at the centre of it all is the great genius of Oscar Wilde, who we witness fading away.

To end, the words of a poet rather than words written about them. Wilde responded to this trauma through his art, and created The Ballad of Reading Gaol: