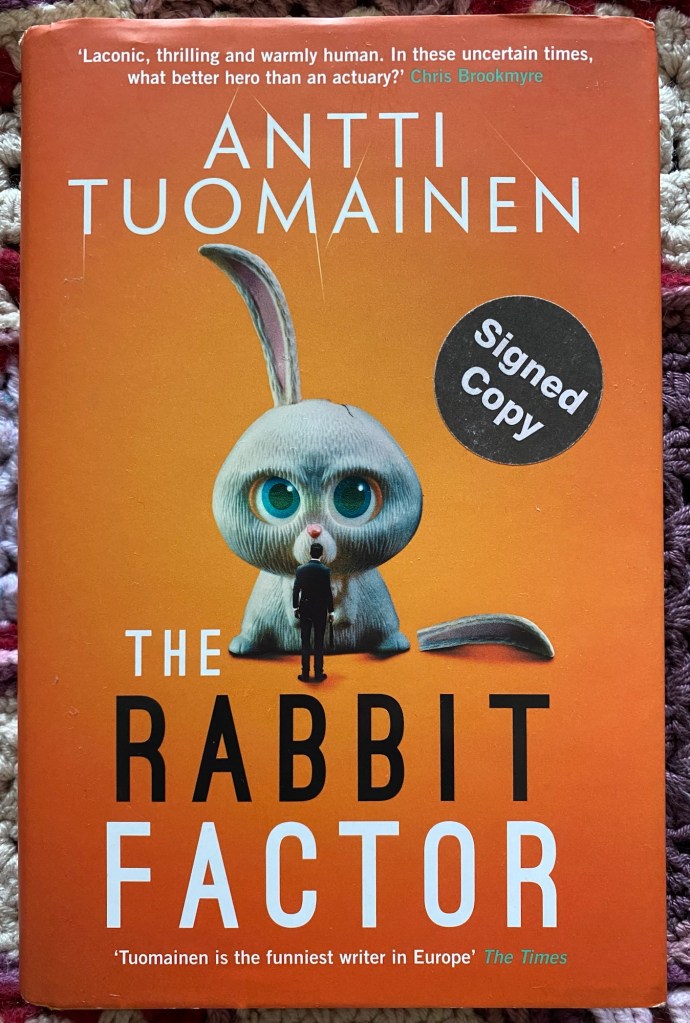

This is my first contribution to Kaggsy and Lizzy’s wonderful #ReadIndies event, running all month. The Rabbit Factor by Antti Tuomainen (2021, transl. David Hackston 2021) is published in the UK by Orenda Books, who describe themselves on their website as: “a small independent publisher based in South London. We publish literary fiction, with a heavy emphasis on crime/thrillers, and roughly half the list is in translation.”

The Rabbit Factor is the first in a trilogy about actuary Henri Koskinen, which had somehow completely passed me by until I read Annabel’s review of the final part, The Beaver Theory. A little while later I saw The Rabbit Theory in my local charity bookshop and took it as A Sign. (As I have mentioned before, I’ll take pretty much anything as A Sign in that shop, and it always results in me buying more books 😀 )

Henri is a man who likes a well ordered, predictable life: “At the age of forty-two I had only one deep-held wish. I wanted everything to be sensible.”

His job as an actuary suits him, using mathematics to predict risk. Unfortunately, what doesn’t suit him is the modern workplace – open plan, noisy and full of corporate-speak about self-actualisation. He is forced into resigning by his boss who hides his bullying behind pseudo-beneficent jargon.

Not long after, Henri is told his brother Juhani has died and he has inherited YouMeFun, an adventure park (not an amusement park) in Vantaa. Unfortunately, before he died his brother inherited their parents’ chaotic approach to life and so Henri finds himself faced with:

“An unbearable lack of organisation, staggering maintenance bills, unproductive use of man hours, economical recklessness, promises nobody could keep, carts that quite literally moved at tortoise speed? I raised my fingers to my throat and checked the position of my tie. It was impeccable.”

Juhani was also in hock to gangsters, two of which – Lizard Man and henchman AK – keep turning up to menace Henri with horrible regularity and conviction. No less threatening, but considerably less violent, is police officer Osmala who similarly seems very interested in YouMeFun and Henri. And so Henri finds himself under enormous pressure and with only his maths skills to fall back on.

“I resigned because I couldn’t stand watching my workplace turn into a playground. Then I inherited one.”

I think maybe this novel passed me by because it can be classified under Nordic-noir, and I don’t read a great deal of that. What I read I enjoy, but I choose carefully because I am a delicate flower and not really in the market for gruesome crimes. Now, there are gruesome deaths in The Rabbit Factor, but I managed these fine. The details aren’t dwelt upon and they are surrounded by such surreal silliness that the focus is more on the ridiculousness of Henri’s situation than violence.

The tone is also not noirish. One of the blurbs in my edition mentions the Coen brothers, and this is a good parallel: while there is darkness to the tale, there is also humour and humanity. Henri’s unlikely colleagues include Esa, the US-marine obsessed security officer; sweet Kristian who is unable to see that his total ineptitude is what prevents him from becoming general manger; Minttu K who seems to know about marketing if she could only stop self-medicating with alcohol; Venla who never arrives for a shift; and quietly efficient Johanna who runs the kitchen and actually seems able to do her job.

There is also Laura Helanto, manager and frustrated artist, who causes feelings to arise in Henri that he doesn’t fully understand. It’s a confusing time for him all round…

“But recent events have taught me that what once seemed likely, as per the laws of probability, is more often than not in the realm of the impossible. And vice versa: what once I would have been able to discount through a simple calculation of probability ratios and risk analysis is now in fact the entirety of my life.”

I really enjoyed The Rabbit Factor. The deadpan narration of Henri is so well-paced that it manages to also be completely engaging. His focus on detail grounds the ridiculousness of his situation so it remains believable, carrying the reader along on Henri’s absurd journey.

“Even as a child I saw mathematics as the key. People betrayed us, numbers did not. I was surrounded by chaos, but numbers represented order.”

The characterisation is equally finely balanced. Henri and his colleagues could so easily be caricatures but instead you end up rooting for these disparate individuals. Tuomainen isn’t remotely sentimental but he is kind to the people he creates. The humour is derived from the situation, never laughing at the people themselves. They change under Henri’s stewardship, and he in return finds himself behaving in ways that surprise him more than anyone:

“I say something I could never have imagined hearing myself say. ‘This doesn’t make any sense. But it has to be done.’”

Last year I decided I would buy one book a month from an independent publisher or bookshop. I think Henri would agree that the probability of my next two purchases in this regard being his adventures in The Moose Paradox and The Beaver Theory are pretty high…

To end, I was so tempted to choose Chas & Dave’s Rabbit, as I absolutely loved that song when I was little (it was released when I was four years old, and I thought they were singing about actual rabbits). But alas, my adult sensibilities prevent me from adding a song about silencing women to the blog 😀 So instead here is a literature-inspired song about drugs rabbits: