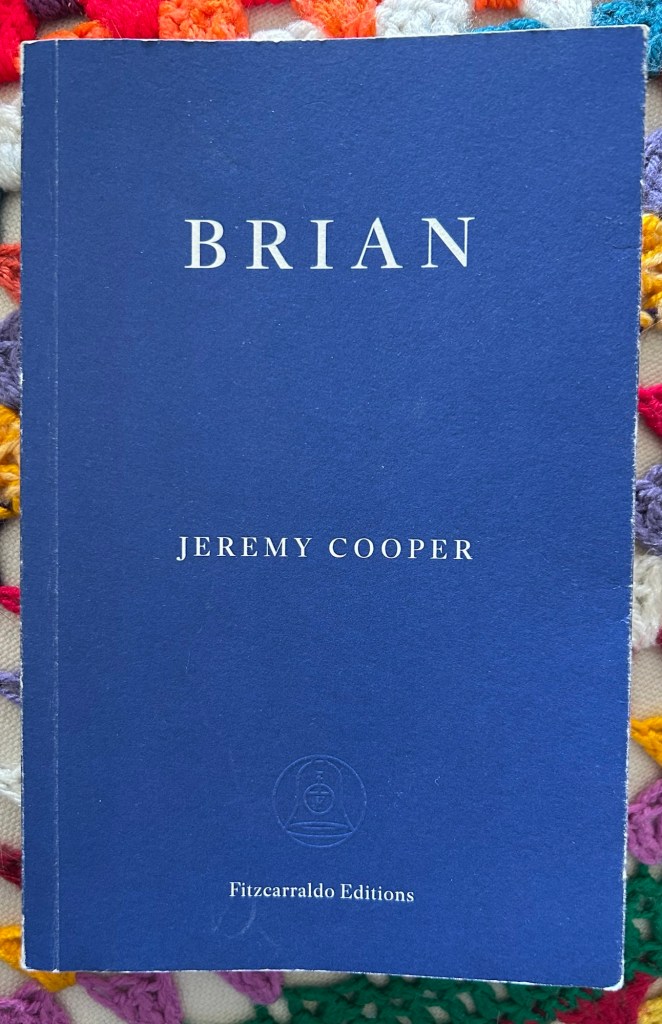

Brian – Jeremy Cooper (2023) 180 pages

Brian by Jeremy Cooper is a book which I knew I would absolutely love. I’m always in the market for tales of loners finding their tribe and building tentative friendships, and Brian had the added bonus of being largely set at the British Film Institute (BFI) cinema on the South Bank. I’m not sure how long I’ve been a member of the BFI but I think it’s about 25 years. Like Brian, when I joined it was called the National Film Theatre (NFT) and it’s a place that has brought much joy over the years.

Brian works at Camden Council, enjoying the predictability of his self-devised filing system and trying to avoid socialising with his colleagues. He lunches every day at the same place with its friendly but unobtrusive manager Lorenzo, and heads home to his flat. He just about keeps his anxiety at bay, most of the time.

“Keep watchful. Stick to routine. Protect against surprise.”

We later learn of Brian’s early childhood trauma that has contributed to his way of living, without him being overly pathologized.

“Learn quick as lightning from your mistakes or die, his mother melodramatically threatened him as a boy. And meant it, he had come to understand.”

He changes his routine one day to attend a revival of a film he’d missed the first time round, Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales. This outing changes his life, as he finds the joy of the BFI programmes and how to not be in his flat, or entirely in his own company, in a way which isn’t overwhelming.

“Brian made the vital discovery that night that something he needed to be true proved to be so: that a nakedly emotional film on themes and feelings close to his own story did not necessarily shake alive his stifled memories of the past.

He was safe. The narratives of others were not his.”

In the foyer he notices a group of regulars chatting:

“Participation in the gathering of buffs appeared to be unconditional – the fact that they were all white males, no women, was more a matter of endemic social habit than the individual prejudice of the buffs, Brian felt, in recognition of his own narrow conventions.”

Cooper’s creation of the buffs is carefully balanced. They are enthusiasts, who welcome other enthusiasts. There is no gate-keeping of film, no declarations of what is a ‘good’ film. Any snobbery is side-stepped. As Brian discovers and develops an abiding love of mid-twentieth century Japanese film, he does so with feeling, without having to intellectualise it, although he always reflects and makes notes afterwards.

“Brian tended to experience film in the moment of watching, for what it meant to him right then, regardless of when it was made or set or how accurate in pretension it might or might not be.”

Time passes, and the BFI becomes another of Brian’s routines, but with the new contained within it: all the films to experience and explore. Alongside this, his relationships with the other buffs develop, albeit at snail’s pace:

“To Brian the most extraordinary occurrence during the first decade of his every-evening visit to the BFI was the incremental formation of what he had come to accept as friendship.”

Brian definitely had an extra resonance for me, describing a London I recognised, journeys I’ve undertaken and a particular place which has a special place in my heart. There were so many echoes, from grieving the closure of the Museum of the Moving Image to Brian being an inpatient at UCLH the same time as I worked there. But I hope my response won’t alienate anyone reading this post. It has such wide-ranging appeal beyond the specifics.

Brian is a beautifully tender novel about community, friendship, and passion. It shows the deep value of a life well-lived, when outwardly that life seems unremarkable, because it is quiet and deliberately demands so little of others. It is a novel about the value of art in our lives and the value of people in our lives, accepted on their own terms.

“Brian recognised for that his entire pre-BFI life he had been a mouse, a termite, shut in dark tunnels of his own creation. Not that he had now become a lion, of course not. More of a squirrel.”

There’s a lovely interview with Jeremy Cooper about writing Brian on the BFI website here.