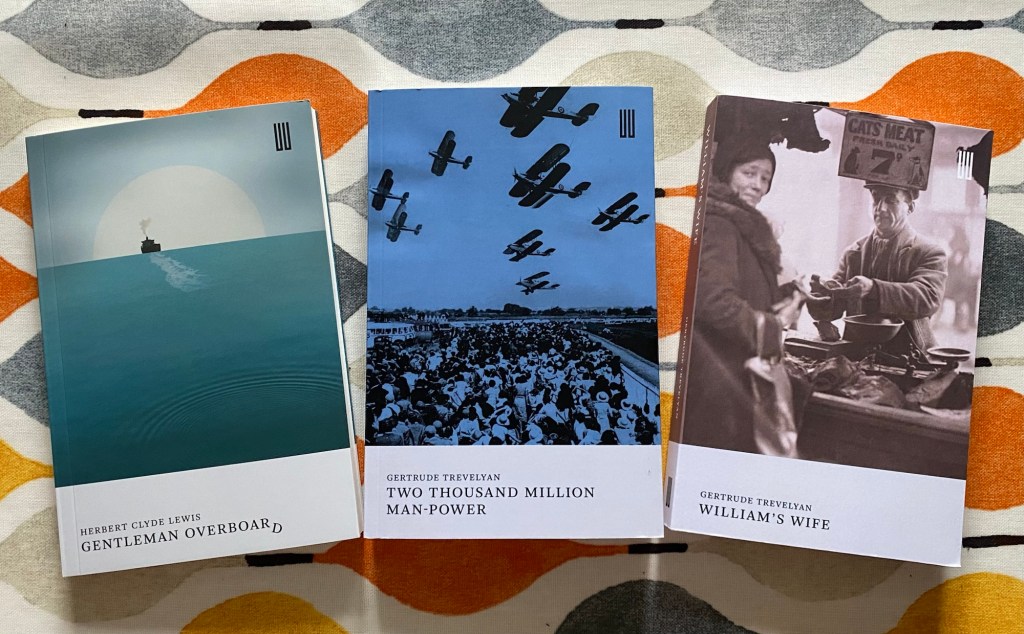

During this final week of Kaggsy and Lizzy’s brilliant #ReadIndies event, I’m going to focus on three books from Boiler House Press, and their Recovered Books series, which brings “forgotten and often difficult to find books back into print for a new generation to enjoy.”

I bought these books last year after Brad Bigelow, founder of www.neglectedbooks.com and inspiration for the series, tweeted about how precarious things were. This is why #ReadIndies is such a great event for encouraging support and celebration of indie publishers, whose survival is never guaranteed.

In this first post, I’m looking at a tragi-comic novella, Gentleman Overboard by Herbert Clyde Lewis (1937).

Henry Preston Standish, “one of the world’s most boring men”, is aboard the SS Arabella steamship en route from Hawaii to Panama. When he slips on some grease he finds himself plunged into the middle of the Pacific Ocean, with hopes of rescue looking pretty slim.

When he first falls overboard, he finds it hard to raise his voice to shout for help, so deeply ingrained is his social conditioning.

“Men of Henry Preston Standish’s class did not go around falling off ships in the middle of the ocean; it just was not done, that was all.”

As he treads water waiting for the Arabella to notice his absence, he reflects on a life where “He did all the proper things, but without enthusiasm.” It’s a real masterstroke that Lewis makes Standish so ordinary, and places him in a situation that is both extreme but also unchanging – a vast expanse of calm ocean. Rather than making the novella dull, it enables a tightly-focussed narrative with a protagonist that inspires sympathy precisely because he is an everyman.

“The whole world was so quiet that Standish felt mystified. The lone ship ploughing through the broad sea, the myriad of stars fading out of the wide heavens – these were all elemental things that both soothed and troubled Standish. It was as if he were learning for the first time that all the vexatious problems of his life were meaningless and unimportant; and yet he felt ashamed at having had them in the same world that could create such a scene as this.”

Poor Standish takes time to realise the hopelessness of his situation, veering from imagined conversations with his family – still framing his experience within his social milieu even when the nearest person is miles away – to considering drowning as an abstract notion rather than an impending reality:

“It would not be so terrible to drown if a man went about it sensibly, without losing his head.”

Back on the Arabella, the remaining eight passengers take time to realise Standish is missing. Once they do, they invent a trauma for him – his loyal wife has, in their minds, run off with a “gigolo” – and start rewriting their experience of him in this light.

The humour in Gentleman Overboard is finely balanced. Standish’s desperate holding onto behavioural norms which are gradually shed as the enormity of his situation dawns on him, and the entirely fictional life story the other passengers invent for him, poke fun at the ridiculousness of human behaviour. But Lewis never suggests it is funny that Standish is in mortal danger, or that his dullness should mean it’s any easier for the reader to bear witness to his imminent death.

Brad Bigelow’s Afterword explains reviewers thought Gentleman Overboard both too short (The Saturday Review) and too long (Evelyn Waugh). I agree with those who felt the length was just right. It was long enough to create a moving portrait of a man, but short enough that the tight narrative’s commentary on human existence was made with the lightest touch. Truly memorable.

“But now he saw clearly that life was precious; that everything else, love, money, fame, was a sham when compared with the simple goodness of just not dying.”