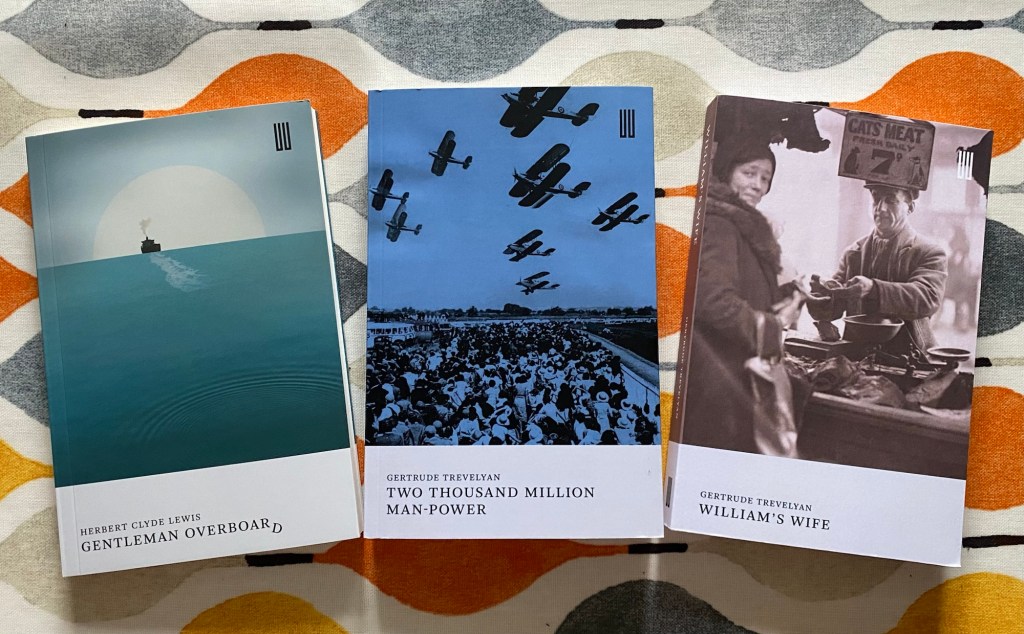

Last year Kaggsy and Lizzy’s brilliant #ReadIndies event led to me discovering Gertrude Trevelyan’s novels Two-Thousand Million Man-Power (1937) and William’s Wife (1938). These are published by Boiler House Press, part their Recovered Books series edited by Brad Bigelow, founder of www.neglectedbooks.com, which brings “forgotten and often difficult to find books back into print for a new generation to enjoy.”

#ReadIndies 2025 felt a perfect opportunity to return to Gertrude Trevelyan and her 1934 novel, As It Was In The Beginning, also part of the Recovered Books series.

This was quite different in style to her other novels I’d read, sustaining stream-of-consciousness. This approach lent itself perfectly to the story, as a woman lies dying in a nursing home, remembering her life.

“Alone with the white sheets and the polished floor and the fire crackling jerkily in the sunken grate and the sun beating against the yellow blinds, and the dull white furniture. All quite clean. Everybody finished up and gone.”

Millicent is well-to-do, formerly Lady Chesborough. She isn’t particularly likeable: she is grouchy, ill-tempered, and rude to the nursing staff. We are privy to her dismissive, judgmental thoughts about those who care for her.

“Oh, so it isn’t the pink-cheeked one this time. Thin and sallow. Dark. Sister, that’s it. Scrubbed all the pink out with the carbolic. Suppose a Sister has been scrubbed longer than a nurse.”

Millicent is also vain about looking younger than she is, about her slender frame and her hair. The reader is aware that she may no longer look as she thinks she does. In this way her vanity is almost defiant, a refusal to accept what is happening to her. It is also bound up in her affair with a younger man, Phil, who used her for money after her husband died.

“That slow smile that seemed to pick things up and weigh them and find they weren’t worth your while and put them down with gentle derision: knowing it was nothing, but not wanting to hurt too much.”

Millicent’s awareness of Phil’s caddishness comes and goes. Her reminiscences are interwoven with her present, muddling her memories with visits from her niece Sonia, the doctor on his rounds and the nurses she is so rude about.

This so well done, meaning the reader becomes a detective, working out what is real, what is imagined, what is memory; what is Millicent’s self-delusion from the time and what is delusion now.

We are then taken back to her marriage with Harold, and Trevelyan deals frankly with Millicent trying to fit in with the expectations for a privileged woman at the start of the last century, and how this stifles her needs and wants, including sexual desire.

“It wasn’t a woman Harold married, but a shell: that’s the truth of it. Something correct in white satin, labelled The Bride.”

Trevelyan doesn’t demonise Harold, but shows how he and Millicent are both products of their time. (Although never specified, I’ve assumed Millicent was born around the 1880s, to be in her fifties or thereabouts when the novel was published, and coming of age in Edwardian England.) They are unable to voice what is lacking for them, and struggle to understand this lack when they have done all that is expected. Millicent has a brief outburst of passion which shocks Harold, and they retreat into distance.

“It was that way of appropriating his surroundings; everything having to fit into a relationship with himself. My house. My wife. Yes, that’s it: Harold’s wife, not myself. That’s what I felt, all those years. My wife, my dog: though he was courteous enough: I’m not fair to Harold. Never could be fair to him. He was too fair himself in that cold way. Not that I ever wanted him to be anything but cold: it was just that which made things bearable: that routine of courteous remoteness we’d settled into.”

This leaves her vulnerable to the later manipulations of Phil, who offers her sexual passion in return for her money.

As Millicent leaves the present further behind, the narrative focuses more and more on her reminiscences. It is expertly done, as the nurses and the clinical surroundings fade further away.

We learn of her childhood, and her struggles as she is taught societal expectations. Her relationship with her first love, a childhood friend, is affected negatively when she becomes old enough to have to put her hair up and can no longer play with him as they used to, as she is now considered a woman rather than a girl.

Millicent’s past explains her choices – and lack thereof – so clearly. As a child she found her body cumbersome. She feels she failed Harold by not giving him a child. She worries she is not enough for Phil because she is nearly old enough to be his mother.

“Don’t want to be a little girl. Don’t want to be a grown up either, grown-ups are silly. They don’t know anything. Don’t ask so many questions: that’s when they don’t know things. Don’t be silly, you’ll know that when you grow up, you’ll find that out soon enough, plenty of time for that when you’re older, little pitchers have long ears, little girls should be seen and not heard curiosity killed the cat.”

Trevelyan uses Millicent to explore the disproportionate focus put on (privileged Edwardian) women’s appearance as their main role and contribution. She has her vanities because society has told her this is her value. There is a sense that as she leaves her body behind, Millicent is achieving the freedom she always wanted.

“I don’t know why people should look at me like that. I suppose they can see I’m not anything. I don’t see how they can see I’m not anything. They’re all solid and I’m hollow, but they can’t see that.”

I would absolutely urge anyone to pick up Trevelyan, but As It Was In The Beginning is probably not the best starting point. I’m fine with stream-of-consciousness, but I thought the first part with the memories of Phil was slightly too long and could have done with an edit. The other two novels I have read by her I thought were stronger, and more approachable in style.

However, I thought stream-of-consciousness was perfect for this story. As It Was In The Beginning provides a powerful exploration of the role of women at that time in a way that is intensely personal, while making astute observations about society. Trevelyan is such an accomplished writer who always manages to drive home her wider points without ever losing sight of her characters. I’m so glad Boiler House Press have rescued three of her novels as she deserves to be so much better known.