Dear reader, it’s been so long. I’ve missed you, but the preparation for finals and my last piece of coursework took over. Now I have finished writing the definitive essay on Cary Grant’s performance of gender ambiguity (OK, I’ve written an essay on Cary Grant’s performance of gender ambiguity) I have a brief respite which I choose to spend blogging. Away we go:

The Bridge concluded almost two months ago and I’m still bereft. In my day off between coursework and revision I’ve been watching BBC4’s replacement foreign-language thriller Salamander, and although excellent, it’s not The Bridge:

(Image from http://www.noblepr.co.uk/Press_Releases/arrowfilms/thebridge.htm )

I love Saga, I love Martin, I love the way their relationship developed in the second season, I love Saga. I know I’ve said I love Saga twice, but this is because I have a girl-crush, the like of which I haven’t experienced since The Killing’s Sarah Lund:

(Image from http://www.krishk.com/2014/01/top-socially-challenged-detectives/ )

How I wish I was effortlessly cool and Nordic, with scrappy long hair, Faroe Isle jumpers, leather trousers and emotional reticence. Unfortunately I’m perennially uncool, I’m British, my hair is an inch long, I look terrible in chunky jumpers and leather trousers and I’m emotionally incontinent. Otherwise the similarities between me and these two women are really quite remarkable.

Now, I know the socially inept detective is becoming something of a cliché, but I’m a huge fan of many of them (see here for how I excited I became over Sherlock) and I miss Saga. It was this which prompted me to start reading The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion (Penguin, 2013) the day after The Bridge finished. It’s not a detective novel, but it does have a main protagonist who is highly intelligent, socially awkward, inflexible, unable to read social cues and has a tendency to respond to things that are said literally. Perfect, just what I needed to fill the Saga-shaped hole in my life. Don Tillman is a geneticist who wants to get married. Having tried dating and found that “the probability of success did not justify the effort and negative experiences” (how many single people out there can relate to that statement?)Don devises a questionnaire “a purpose-built, scientifically valid instrument incorporating current best practice to filter out the time wasters, the disorganised, the ice-cream discriminators, the visual-harassment complainers, the crystal gazers, the horoscope readers, the fashion obsessives, the religious fanatics, the vegans, the sports watchers, the creationists, the smokers, the scientifically illiterate, the homeopaths, leaving, ideally, the perfect partner, or, realistically, a manageable shortlist of candidates”. Into Don’s life breezes Rosie, who it’s safe to say, does not fit his criteria for the ideal mate. She is chaotic, confrontational, encourages him to drink, watches sport and is a smoker. They are perfect for one another.

““Where do you hide the corkscrew?” she asked.

“Wine is not scheduled for Tuesdays.”

“Fuck that,” said Rosie.

There was a certain logic underlying Rosie’s response.

[…]I announced the change. “Time has been redefined. Previous rules no longer apply. Alcohol is hereby declared mandatory in the Rosie Time Zone.””

Although Don is unusual, in many ways his situation is ordinary: so many people spend time constructing their ideal mate they forget to think about the relationship they want, missing what’s actually in their lives, and who it’s worth compromising a bit of ourselves for. Simsion looks at this aspect of oh-so-human folly with a comic eye, and there are some hugely funny scenes as Don tries to get to grips with situations where he is hopelessly out of his depth: attending a “formal” function in top hat and tails, practising sex positions with his teaching skeleton and being walked in on by his boss. Because Don is aware of the humour but doesn’t quite get it, the scenes are told in an utterly deadpan style that is hilarious, but you’re never laughing at Don, just the situations he finds himself in. This is because you are completely rooting for the character. Simsion manages quite a feat with Don: a resolutely pragmatic, measured voice that still manages to create a person that you really feel for, and a novel of real warmth and humanity. Simultaneously, Don exposes the fakery that goes along with social skills and fitting in – the office politics, the lies and infidelities – that he is incapable of, making you question what is of real value, rather than what just makes life easier. If you’d told me I’d like a book I would describe as “sweet and romantic” I’d tell you (with a raised eyebrow of scepticism, reader) that it really wasn’t my taste. But, just like Don, I stepped outside my comfort zone, tried something new, and was completely won over.

For my second social outcast I’ve chosen the Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz (Faber, 2008). Poor Oscar: he’s massively nerdy and all he wants is to love and be loved. “Oscar showed the genius his grandmother insisted was part of the family patrimony. Could write in Elvish, …knew more about the Marvel Universe than Stan Lee, was a role-playing game fanatic….Perhaps if like me he’d been able to hide his otakuness maybe shit would have been easier for him, but he couldn’t. Dude wore his nerdiness like a Jedi wore his light sabre or a Lensman her lens. Couldn’t have passed for Normal if he’d wanted to.” An incurable romantic who dreams of becoming the “Dominican Tolkien”, Oscar’s life will never play out how he wants it to.

He lives with his mother Beli and rebellious sister Lola, and as we learn about all three of them, we learn about the recent history of the Dominican Republic and its impact on a family. The novel makes frequent use of footnotes, which generally I dislike but which worked well here, detailing political history in the distinctly non-academic (though learned) voice of Yuniour, Lola’s boyfriend, serial womaniser and narrator. The family are thought to be under the sway of a fuku “the Curse and Doom of the New World”, and certainly all are subject to violence and hardship, Beli in Dominica and her son and daughter in the United States.

There is a touch of magic realism as the family are also protected by a guardian animal that appears to them in times of extreme distress: “there appeared at her side a creature that would have been an amiable mongoose if not for its golden lion eyes and the absolute black of its pelt. This one was quite large for its species and placed its intelligent little paws on her chest and stared down at her. You have to rise.” The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao has plenty to say about the immigrant experience, the price of assimilation and the inability to assimilate to the societies we find ourselves in, and the self-definition we express through the language we use. The novel has references I didn’t get: Spanish phrases and nerd-allusions, but it didn’t matter. The refusal to be sentimental and the triumph of human spirit in the face of violence and tragedy meant this novel really spoke to me even if I didn’t grasp all the intricacies. It was funny and tragic, and truly moving.

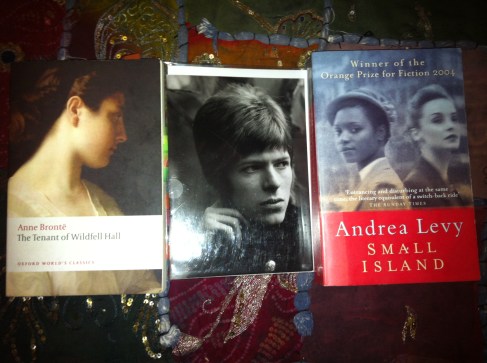

Here are the books with the lovely Sofia Helin who plays Saga (you can tell it’s the actor & not the character because she’s smiling):