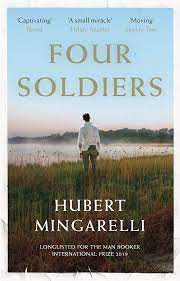

Four Soldiers – Hubert Mingarelli (2003 transl. Sam Taylor 2018) 155 pages

I really loved Hubert Mingarelli’s A Meal in Winter when I read it six years ago and so I was overjoyed to find a copy of Four Soldiers in my beloved local charity bookshop. This had a lot in common with its predecessor, being a sparse tale of servicemen which focussed on their humanity rather than their role in conflict. But it was resolutely its own tale too.

The four soldiers are friends thrown together by circumstance during the Russian Civil War in 1919. Resourceful, skilled Pavel, naïve gentle giant Kyabine, quiet, thoughtful Sifra and the narrator Benia. They keep each other company during the tedium of waiting for orders, close to the Romanian border:

“Because we didn’t know where we would be tomorrow. We had come out of the forest, the winter was over, but we didn’t know how much time we would stay here, nor where we would have to go next. The war wasn’t over, but as usual we didn’t know anything about the army’s operations. It was better not to think about it. We could already count ourselves lucky to have found this pond.”

What is so striking about the soldiers is how terribly young they are. We are never told their ages, but their behaviour, their lack of experience, their superstitions – all emphasise that they are little more than children caught up in something far beyond their control, for which they may have to pay the highest price.

Their concerns are ordinary, not political or idealistic. They play dice; they swim; they smoke; Pavel has nightmares; they take turns to sleep with a watch that contains a picture of a woman that they think brings them luck.

Mingarelli doesn’t seek to explain how they ended up there or what they hope for beyond it. By focussing on the present he is able to convey how caught they are by circumstance, how hope lingers but is unexpressed.

“Barely had we finished drinking that tea before we became nostalgic for it. But, all the same, it was better than no tea at all.”

The simplicity of the plot, imagery and prose is so finely balanced. Mingarelli conveys a vital story that needs no adornment while at the same time driving home its importance and universality.

“I advanced. But I did so evermore sadly. The sadness was stronger than me. It was because of the smell of potatoes slung over my shoulder. It didn’t evoke anything precise, that smell. Not one specific event, in any case. What it evoked was just a distant time.”

Four Soldiers isn’t remotely sentimental or sensationalist, and it’s the ordinariness it depicts that makes it so devastating, and humane.

“The silence and the darkness covered us.

Then suddenly, almost in a whisper: ‘I wrote at the end that we had a good day.’

It was very strange and sweet to hear him say that, because, my God, it was true, wasn’t it? It had been a good day.”

Susan at A Life in Books, a great champion of novellas whose reviews are a significant contributor to my ever-spiralling TBR, has written about Four Soldiers here.