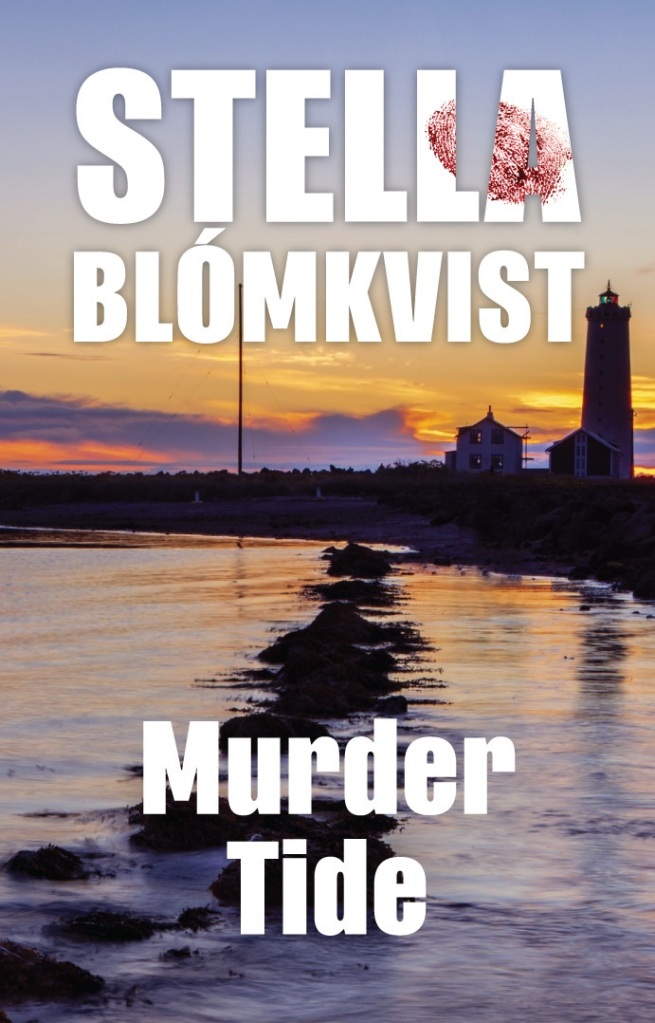

Today I’m taking part in a blog tour for Corylus Books, a lovely indie publisher with a focus on translated crime fiction.

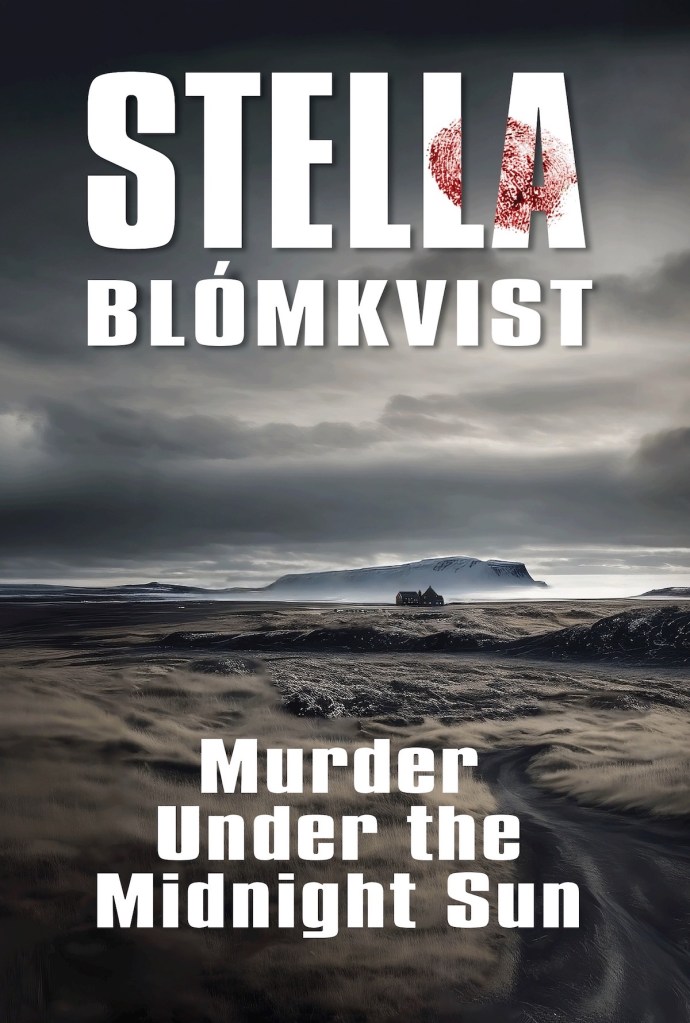

Murder Tide (2017, transl. Quentin Bates 2024) is the third Stella Blómkvist mystery I’ve read as part of Corylus’ blog tours and I enjoyed reacquainting myself with her world: her daughter Sóley Árdís; the deepening relationship with Rannveig; her cousin Sissi; newshound Máki; and of course her antagonistic relationship with the local police.

Here is the blurb from Corylus Books:

“Left to drown by the rising tide at the dock by Reykjavík’s Grótta lighthouse, the ruthless businessman with a murky history of his own had always had a talent for making enemies.

The police have their suspect – who calls in Stella Blómkvist to fight his corner as he furiously protests his innocence. Yet this angry fisherman had every reason to bear the dead man a grudge.

It’s a busy summer for razor-tongued, no-nonsense lawyer Stella. A young woman looking for a long-lost parent finds more than she bargained for. An old adversary calls from prison, looking for Stella to broker a dangerous deal with the police to put one of the city’s untouchable crime lords behind bars at long last.

Is the mysterious medium right, warning that deep waters are waiting to drag Stella into the depths?”

Murder Tide is grounded in the realities of Iceland in 2011. Grímúlfur, the murdered man, was nicknamed the ‘Quota King’ and made a lot of money out of Iceland’s financial crash in 2008. People who took out enormous foreign currency loans had to hand over their businesses to the banks, who then sold on the loans to their cronies who had the loans written off. Grímúlfur was one of the cronies and he bought fishing quota rights too.

“‘The quota system has split the country for the last two decades, as it has provided a chosen few with great wealth just as it has wrecked many rural communities and added to the inequality and injustice in Icelandic society,’ Máki writes.”

Stella’s client is a fisherman who suffered under this system, and she soon finds out that as well as the many who Grímúlfur ripped off, his family bear him some pretty significant grudges too.

At the same time she is helping a young woman called Úlfhildur find her birth father, who unfortunately for Úlfhildur seems to be a truly sinister man married to a threatening woman, who together run a cult.

Her third client is the decidedly dodgy Sævar whose case highlights police corruption and reinforces Stella’s cynical world view:

“Bitter experience has taught me that there’s nobody in this world who can be trusted. It’s all about uncertainty and coincidence.”

The three strands in Murder Tide are woven together well and even my poor brain managed to keep track of what was happening. The societal commentary felt intrinsic to the plot rather than slowing it down, and I whizzed through this pacy story.

Stella felt more likable in this book and the habit she has of referring to brand names and labouring over material possessions has eased off a bit. She’s leading a slightly more settled life as she and Rannveig continue the relationship which began in Murder Under the Midnight Sun. But Stella’s domestic life is generally in the background, as she tears around working just as hard as ever.

She really does need to stop sexually assaulting people though. This time it was for a different reason than her own gratification, but for a character who is supposed to follow her own moral compass in opposition to self-serving businessmen and corrupt police officers, I would really welcome her incorporating informed consent into her world view.

However, this isn’t a significant part of Murder Tide so please don’t be put off! What worked especially well was the menace of characters and genuine sense of danger, alongside humour. Chapters frequently end with a quote from Stella’s mother, a woman who seems to have had an aphorism for every occasion, ranging from the insightful to the clichéd, the incomprehensible to the remarkably plain-speaking. These really made me smile and kept the character of Stella grounded in a more recognisable reality, while she rode motorbikes at speed, visited career criminals in prisons and exposed corruption with the help of Sissi’s technical expertise.

The tone is also carefully balanced. There were some very dark aspects to Murder Tide, and Blómkvist is expert at conveying these clearly, without ever being gratuitous or voyeuristically gruesome.

As always with Stella’s stories, the pace and plotting worked seamlessly. But what I especially enjoyed in Murder Tide was the deepening characterisation of Stella, and I’m looking forward to seeing where she goes next.

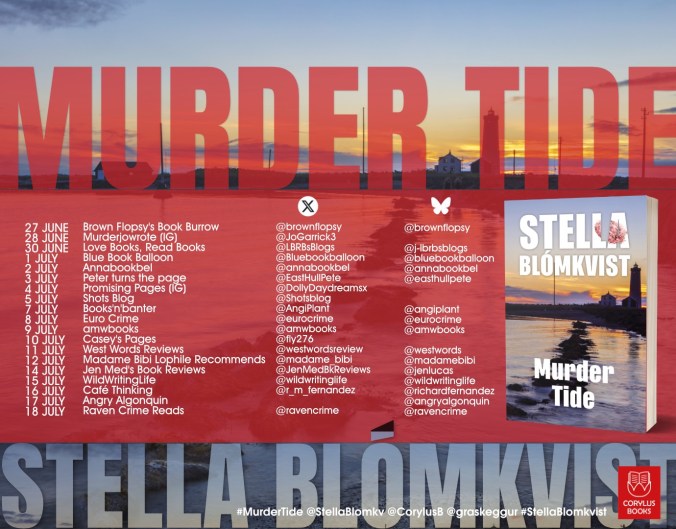

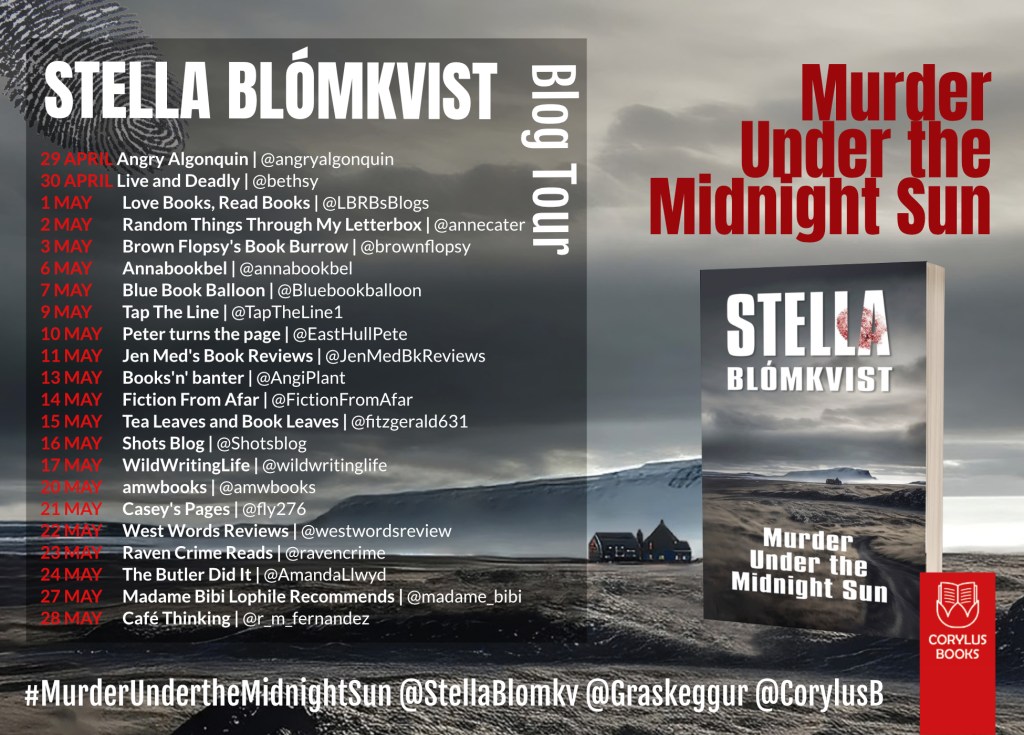

Here are the stops from the rest of the tour, so do check out how other bloggers got on with Murder Tide: