This week’s post was prompted by an elastic band. But first let me confess to a bad habit: I make up stories about people. I’m sure lots of people do. I sit on the train/in the café/bored out of my mind in the supermarket queue and I’ll notice someone and start concocting a whole story about them. Half the time I don’t even realise it’s what I’m doing. A lot of the time I forget this means I can end up staring quite intently at someone, and it’s frankly somewhat of a miracle that I’ve reached my ripe old age without getting my face punched in. If you suffer from this affliction and live in the UK, may I recommend the National Portrait Gallery? A safe space where you are actively invited to go round staring at faces, it’s a haven for the fantasist of this type. So, with my anti-social habit established, let me rewind to the elastic band…

I was on the train to Brighton (hence the title quote about Metro passengers, and an excuse to highlight one of my favourite poems). The man across the aisle from me, facing away, was reading a book whose cover I couldn’t see, and on the little pull down table in front of him he had a bag of crisps. This was a mammoth bag of crisps, and he’d eaten about half, folded over the top of the packet, and secured it with an elastic band wrapped round the packet. After I’d admired his restraint – because if I open a big bag of crisps the entire contents of that bag is getting eaten – I became mesmerised by this elastic band. Where had it come from? Had he brought it with him, planned in advance for just such an eventuality? Or did he carry round bits of stationery (is an elastic band stationery?) just in case events took a turn and he would be called on to secure something? Did he buy the elastic band having eaten half the packet and deciding the crisps needed better containment that just folding the top over? How the hell had this circumstance arisen? He didn’t appear to have any bags with him, just the book and the crisps, so it wasn’t like he had an elastic band conveniently buried in a capacious man bag.

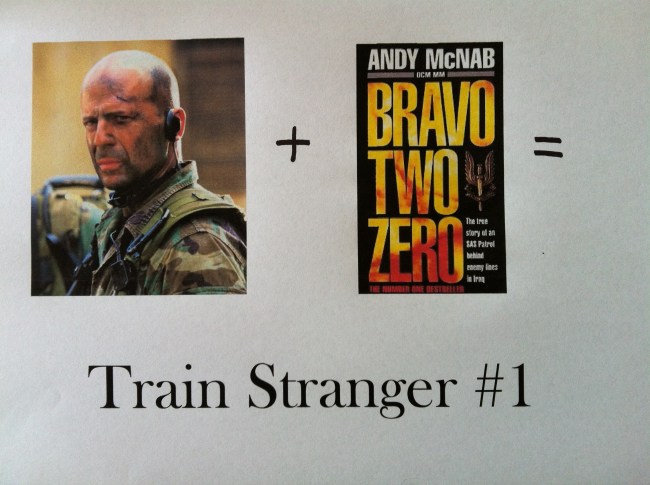

I realise thinking about almost anything other than this elastic band would have been a better use of my time, but I couldn’t help it. This coupled with the man’s appearance – shoulders so big he was halfway in the aisle despite sitting fully in his seat, and a shaved head – convinced me he must be some ultra-capable marine/secret agent type. I was certain the book he was reading was by Andy McNab. And now a shoddy visual representation to keep you going through this long, waffly post:

When he got up to leave I saw the front cover of the book and I couldn’t have got it more wrong. Most unexpected. It was a book the BBC adapted for a Sunday night TV programme, that’s how cosy it was. As my visions of him as MacGyver (or a more recent reference for the youngsters, Michael Weston from Burn Notice) crumbled to dust, I realised that I am rubbish at judging people. I’d either got it totally wrong, or he was some hardcore daredevil marine, who just happened to like cosy reading. Either way my ideas about him based on elastic band usage and reading matter were entirely false. By way of recompense I offer this book recommendation, which I think someone who is fastidious enough to wrap his crisps in an elastic band might enjoy (and yes, I realise this is still me being judgemental – and probably getting it wrong again – sorry, sorry, sorry):

So Many Ways to Begin by Jon McGregor (2006, Bloomsbury) tells the story of David, a museum curator. Working in museums is his vocation, he has loved them since childhood:

“He liked the smell of museums, the musty scent of things dug from the earth and buried in heavy wooden store cupboards. He liked the smell of the polish on the marbled floors, and the way his shoes squeaked as he walked across them. He liked the way people’s voices would drift up and be lost in the hush of the high-ceilinged rooms. He liked the coldness of the glass cases when he pressed his face against them. He liked looking at the dates of the objects , and trying not to get dizzy as he added up how long ago that was. He didn’t understand why people had to ask, why they didn’t enjoy museums as much as he did…”

A friend of his mother’s accidently exposes a family secret, one which sends David into free-fall. As he struggles to comprehend his present in light of his altered past, he curates his own belongings. Each chapter has a heading which refers to an object in David’s life: “handwritten list of household items c.1947”, “pair of cinema tickets annotated 19 May 1967”, “cut fragments of surgical thread, in small transparent case, dated July 1983”. As we learn the meaning these objects hold, we understand David and the life he leads, alongside his mother, wife and daughter. David fully realises the meaning of the minutiae in our lives when he curates an exhibition on the immigrants arriving in Coventry after the war:

“He wasn’t surprised by the interviewees eagerness to loan him their few treasured keepsakes –the watches, the framed photographs, the religious artefacts – trusting him to keep their last attachments to a lost home safe, pushing them gladly into his arms. But what he hadn’t quite been expecting was just how readily people held these things to hand, arranged together in the alcoves of their front rooms, or across a chest of drawers in a bedroom, or filling a glass-fronted cabinet in a kitchen, like miniature museums of their own.”

So Many Ways to Begin is a sensitive portrayal of the intensely personal nature of the physicality of lives, how we ground ourselves in objects and are keepers of our own histories. It is also about the shifting nature of those histories, and how relationships with others, the intangible, is what gives meaning to the tangible.

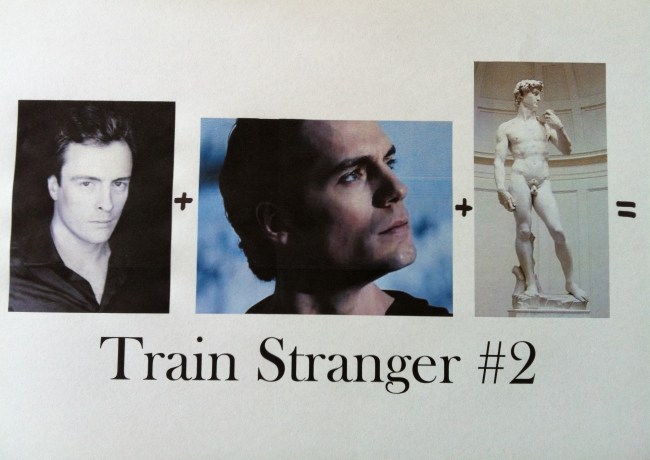

My second recommendation I give to the man who was sitting directly opposite me, (facing me) on the same journey. You, sir, are beautiful. This adjective is overused, applied with alarming regularity to people who simply have capped teeth and a good blow-dry. But you are beautiful: you look like Henry Cavill and Toby Stephens had a baby together, then got Michelangelo in to complete the job. (Seriously, why are you on a train in south London? Shouldn’t you be in a convertible in the south of France?) Shoddy visual representation to keep you going through this long, waffly post:

While I’m on this judgemental trip, I’ll assert that I think you owe it to the world to ensure your mind is as beautiful as your face. Stop reading the free newspapers that litter every train compartment. Yes, that’s what you were doing. It only serves to sully you. I know they’re free, I know everyone does it, but do you know the free paper is owned by the same group as the Daily Mail? And frankly there isn’t a blog post long enough for me to tell you all that’s wrong with that newspaper. So here is my recommendation for reading matter as lovely as your face:

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy (1997, Flamingo) is novel that takes joy in language and is beautifully written. I know some people found it a bit over the top in this regard, but I really enjoyed losing myself in this lyrical novel. It tells the story of a family through the eyes of twins, Estha and Rahel. Roy is a political activist (this is her only novel so far) and there are strong political themes running through the novel, around India’s caste system, economics, and communism. She considers the effect these large forces can have on families and individuals:

“it was a skyblue day in December sixty-nine (the nineteen silent). It was the kind of time in the life of a family when something happens to nudge its hidden morality from its resting place and make it bubble to the surface and float for a while. In clear view. For everyone to see.”

The conflict between the family morality and societal constructs results in tragedy that tears the family apart. The twins are separated at age 7 and only reunited at age 31, where the damage that has been done continues to exert its power. It’s difficult to go into details without giving away great swathes of plot, so I’ll just give you a few little bits. Estha reacts to the events by becoming increasingly silent:

“A raindrop glistened on the end of Estha’s earlobe. Thick, silver in the light, like a heavy bead of mercury. She reached out. Touched it. Took it away. Estha didn’t look at her. He retreated into further stillness.”

The Kerala setting is vividly evoked, such as in the opening paragraph to the novel:

“May in Ayemenem is a hot, brooding month. The days are long and humid. The river shrinks and black crows gorge on bright mangoes in still, dustgreen trees. Red bananas ripen. Jackfruits burst. Dissolute bluebottles hum vacuously in the fruity air. Then they stun themselves against clear windows and die, fatly baffled in the sun. The nights are clear but suffused with sloth and sullen expectation.”

The God of Small Things takes controversial issues shows the impact on individuals bound up in circumstances they cannot control. The beauty of the prose emphasises the drama rather than disguises it, making a powerful and highly readable novel.

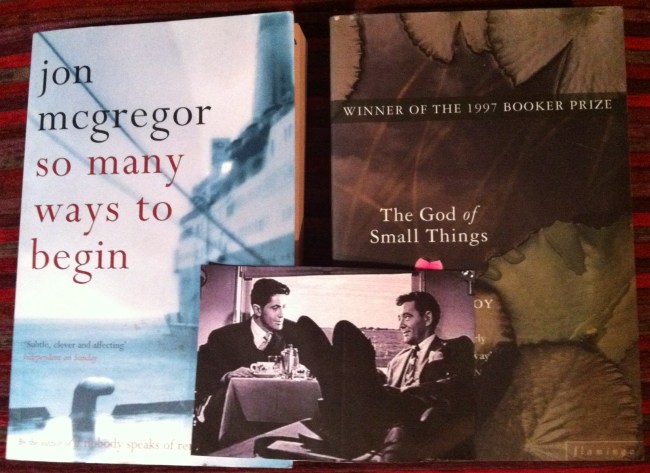

Here are the novels with a scene from Strangers on a Train: