It is a truth universally acknowledged, that the film version of a book is never as good as the original text. Except I don’t think that’s true. This week I’m going to look at two books where I think the film was better, but the novels are still worth reading. Slightly odd tack for a book blog to take, and I may end up regretting this, but let’s crash ever onwards!

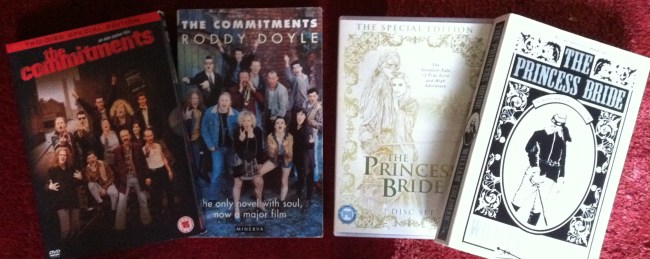

Firstly, The Commitments by Roddy Doyle (1987). Here’s the trailer for the 1991 film, with a brilliant script by the author, in collaboration with the long-term writing partnership of Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais.

The Commitments is Roddy Doyle’s first novel, detailing how a group of white, working class Dubliners set up a soul band together. I think in this novel Doyle is really learning his craft, and his writing gets progressively stronger as he goes along. The Commitments is a far from terrible book, but it’s a bit slight, and filled with so much dialogue it reads more like a script than a novel for much of it. Still, if you’re going to have a novel filled with dialogue it may as well be written by Roddy Doyle, who has a great ear for how people speak and seems to take real joy in capturing it on the page:

“-Grow a pair o’ tits, pal, an’ then yeh can sing with them, said Billy.

– Are you startin’ somethin’?

-Don’t annoy me.

– Here! Said Jimmy. –None o’ tha’.

The time was right for a bit of laying down the law.

-No rows or scraps, righ’.

-Well said, Jim.

– An’ annyway, said Jimmy. –The girls are the best lookin’ part o’ the group.

– Dirty bastard, said Natalie.

-Thanks very much, Jimmy, said Imelda.

-No sweat ‘melda, said Jimmy.

-What’ll we sing? Bernie asked Joey The Lips.

-You know Walking in the Rain?

-Lovely.

– I WANT HIM, Imelda sang.

– It doesn’t exactly have a strong feminist lyric, does it? said James.

– Soul isn’t words, Brother, said Joey The Lips. – Soul is feeling. Soul is getting out of yourself.”

You can see that this is writing really stripped back: minimal punctuation, not always clear who is speaking. The style suits the tale of a bunch of people with very little creating music with only their voices and few instruments. It makes The Commitments a quick read, and the characters are evoked with warmth through minimal authorial intervention. By writing in such a sparse way, Doyle allows the characters to speak for themselves. At other times he uses scant detail, rarely embellished with imagery, to portray the lives of the band:

“’Joey The Lips got one of his dress suits dry-cleaned. Dean crawled in under his bed and found the one he’d flung under there. He soaked the jacket till the muck was nearly all gone. Then he brought it down to the cleaners.

Black shoes were polished or bought or borrowed.”

The Commitments is a well-observed story, evocative and humorous. However, a novel about music will always have much to gain from being filmed; hearing the talented cast of the film give their voice to soul classics brings the characters into being in a way that is nearly impossible in print.

Secondly, The Princess Bride by William Goldman (1973). Here’s the trailer for the 1987 film adaptation, screenplay by the author:

One of my favourite films from childhood that I still love to watch today – a definite winner on a rainy Sunday afternoon. Again, it’s not that the book is bad (the film is scripted by Goldman after all so you wouldn’t expect a great deal of difference) but the film is better. It takes all the best bits of the book and distils them into a fast-paced, funny narrative; the book can be a bit flabby at times by comparison. The film also offers some of the best cameos ever: Billy Crystal as Miracle Max, Mel Smith as the torturer, comic genius Peter Cook as the Impressive Clergyman, as well as a perfectly cast set of main characters. But if you like the film, you’ll like the book. The same dry, silly humour runs through it, and who wouldn’t love a tale of: “Fencing. Fighting. Torture. Poison. True love. Hate. Revenge. Giants. Hunters. Bad men. Good men. Beautifulest ladies. Snakes. Spiders. Beasts of all natures and descriptions. Pain. Death. Brave men. Coward men. Strongest men. Chases. Escapes. Lies. Truths. Passion. Miracles.”

The tale is one of Princess Buttercup, who falls in love with the stable boy Westley. He goes off to seek his fortune, and is captured by the Dread Pirate Roberts, who famously leaves no survivors. Believing her One True Love to be dead, Buttercup agrees to marry the hunting-obsessed Prince Humperdink. Before they can marry she is kidnapped by a gang comprising the cunning Vizzini (“never start a land war in Asia, [… and] never go against a Sicilian when death is on the line”), the giant Fezzik , and genius-swordsman-with-a-vendetta Montoya (“my name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die!”) They are followed by the mysterious Man in Black, who seeks to foil their plans… Will goodness triumph? Will true love conquer all? Yes, of course, to both. This is a lovely escapist fantasy, but at the same time it is a satire on established rule and its abuses, which gives the story a more serious dimension. Prince Humperdink has arranged the kidnap of Buttercup in order to blame a neighbouring country and start a war. (Fill in your own contemporary analogy here.) He tells his henchmen to seek the “villains” in the thieves quarter:

““My men are not always too happy at the thought of entering the Thieves Quarter. Many of the thieves resist change.”

“Root them out. Form a brute squad. But get it done.”

“It takes at least a week to get a decent brute squad going,” Yellin said. “But that is time enough.

[…]

The conquest of the Thieves Quarter began immediately. Yellin worked long and hard each day […] Most of the criminals had been through illegal roundups before, so they offered little resistance.””

Goldman is also able to extend his humour in the novel towards the processes around writing, which he couldn’t do in the film; for example his editor querying his translation of the “original” story by S. Morgenstern:

“this chapter is totally intact. My intrusion here is because of the way Morgenstern uses parentheses. The copy editor at Harcourt kept filling the margins of the galley proofs with questions: […] “I am going crazy. What am I to make of these parentheses? When does this book take place? I don’t understand anything. Hellllppppp!!!” Denise, the copy editor, has done all my books since Boys and Girls and she had never been as emotional in the margins with me before.”

So there we go: two film recommendations as well as two book recommendations in the same post – call it a late Hogmany present from me to you, dear reader. Enjoy!