It was the autumn equinox last week here in the UK, which means summer for us is officially over and everyone’s back at work. For this reason I thought I’d look at the theme of London as it’s where I live and work, alongside eleventy-million others. Those heady summer days are rapidly becoming a distant memory under the realities of train strikes (salt rubbed into the wound of a service so bad it often seems like Southern rail are running a surrealist immersive art installation they’ve forgotten to tell anyone about) and falling temperatures. For this reason, and after the tribulations of The Notebook last week, I’ve chosen 2 comic novels for a bit of light relief.

Firstly, NW by Zadie Smith (2012) or, how I learned to stop worrying and love Zadie Smith, if you will. This is Smith’s fourth novel (she recently published her fifth, Swing Time) and it’s the first of her much-lauded fiction that I’ve truly enjoyed. Until this point I always preferred her journalism and essays, but NW is the point at which her fiction really grabbed me.

Set in the part of London whose postcode gives the book its title, NW experiments with various forms, hopping between stream-of-consciousness, text-speak, first and third person, diagrams… It is a successful approach, creating the multiple voices and sensory overload that London offers, without descending into a chaotic mess. Edgware Road:

“Sweet stink of the hookah, couscous, kebab, exhaust fumes of a bus deadlock. 98, 16, 32, standing room only – quicker to walk! Escapees from St Mary’s Paddington: expectant father smoking, old lady wheeling herself in a wheelchair smoking, die-hard holding urine sack, blood sack, smoking. Everybody loves fags. Everybody. Polish paper, Turkish paper, Arabic, Irish, French, Russian, Spanish, News of the World. Unlock your (stolen) phone, buy a battery pack, a lighter pack, a perfume pack, sunglasses, three for a fiver, a life size porcelain tiger, gold taps.”

Leah, Natalie (who used to be called Keisha), Felix and Nathan grew up on the same Caldwell estate and went to the same school. As adults, their lives have diverged, but they all still live in the area (Willesden) and their stories overlap and layer one another, broadening each of their individual tales. Leah and Natalie are each other’s oldest friend. Both are married – more or less happily – and employed, building their lives. But whereas Natalie spent the 90s knuckling down to work and is now a successful barrister, Leah spent it enjoying rave culture and now has a socially responsible but low-paid job, which creates a tension in their relationship:

“Leah watches Natalie stride over to her beautiful kitchen with her beautiful child. Everything behind those French doors is full and meaningful. The gestures, the glances, the conversation that can’t be heard. How did you get to be so full? And why so full of only meaningful things? Everything else Nat has somehow managed to cast off. She is an adult.”

Of course, when we get to Natalie’s version of the story Leah has alluded to, we realise all is not as it seems. Natalie is not entirely happy; she has not shrugged off Caldwell, nor does she entirely want to. There are areas of her life where she still refers to herself as Keisha, and when she gives birth to the first of her beautiful children it is her childhood friends and family that give most comfort:

“People came with advice. Caldwell people felt everything would be fine as long as you didn’t actually throw the child down the stairs. Non-Caldwell people felt nothing would be fine unless everything was done perfectly and even then there was no guarantee. She had never been so happy to see Caldwell people.”

Another section of the novel follows recovering addict Felix around the borough. He is emerging from a destructive life into something more positive. As he moves around the area, between the people of his old life and new, his story simultaneously captures the transformation which his home town is undergoing:

“He steadied himself with a hand on the Tavern’s back door: fancy coloured glass now and a new brass doorknob. Wood floors where carpets used to be, real food instead of crisps and scratchings. About six quid for a glass of wine! Jackie wouldn’t recognise it. Maybe by now she’d be one of those exiles on the steps of the betting shops, clutching a can of Special Brew, driven from the pub by the refits.”

Nathan meanwhile, beautiful and talented at school, now a physical wreck, has not managed to pull himself out of the sort of life Felix had been living. NW is funny and sad, effectively capturing born –and-bred Londoners at a specific time in an ever-changing city. As a born-and-bred Londoner myself, around the same age as Zadie Smith and therefore her protagonists, I thought it was highly effective in capturing place, time and voice(s). I still think Zadie Smith’s editor needs to be heavier-handed, and one of the characters makes a leap at the end that I thought didn’t quite hold up, but NW means I’m now really looking forward to reading Swing Time.

Not the only member of her family to engage with ideas around language, here is Zadie’s brother Ben aka comedian/rapper/actor Doc Brown, proving that apparently the whole family are good-looking, talented and witty, damn them (little bit rude and mild swears):

Secondly, Capital by John Lanchester (2012). In 2010 former journalist Lanchester wrote a non-fiction book, Whoops!: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No-one Can Pay (2010) about the credit crunch. This is a fictional look at the same time, through the residents of Pepys Road in south-west London. Pepys Road, like much of London, has seen the value of the property rise exponentially:

“For most of its history, the street was lived in by more or less the kind of people it was built for: the aspiring not-too-well-off. They were happy to live there, and living there was part of a busy and determined attempt to do better, to make a good life for themselves and their families. But the houses were the backdrop of their lives: they were an important part of life but they were a set where events took place, rather than the principal characters. Now, however, the houses had become so valuable to people who already lived in them, and so expensive for people who had recently moved into them, that they had already become central actors in their own right.”

Hence Capital is about the capital city, and also about the financial capital which the city propagates and runs on.

“She wasn’t sure how to make money, exactly, but anyone with eyes could see that it was everywhere in London, in the cars, the clothes, the shops, the talk, the very air. People got it and spent it and thought about it and talked about it all the time. It was brash and horrible and vulgar, but also exciting and energetic and shameless and new”

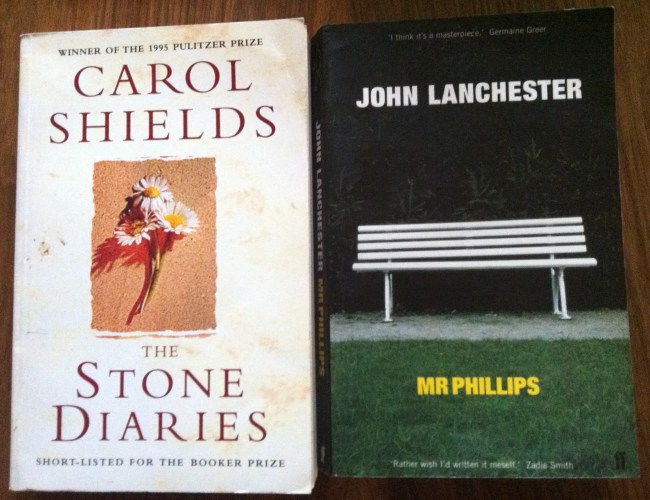

In Mr Phillips, Lanchester wrote a slim novel detailing one man’s life over one day. By contrast, this is a 577 page (in my edition) novel takes in the lives of many: Petunia, an elderly lady who has lived in Pepys Road most of her life and her grandson, a Banksy-style artist; Roger and Arabella, a city worker and his materialist wife, their Hungarian nanny and Polish builder; the British Muslim family who run the corner shop; the Senegalese footballer whose club owns one of the houses; the Zimbabwean refugee who works illegally as a traffic warden, ticketing the Aston Martins and Jeeps in the road.

Unsurprisingly, it is Roger and Arabella who are most affected by the financial collapse. At the start of the novel Roger is anticipating his million-pound bonus:

“His basic pay of £150,000 was nice as what Arabella called ‘frock money’, but it did not pay even for his two mortgages. The house in Pepys Road was double-fronted and had cost £2,500,000, which at the time had felt like the top of the market, even though prices had risen a great deal since then. They had converted the loft, dug out the basement, redone all the wiring and plumbing because there was no point in not doing it, knocked through the downstairs, added…”

The chapter continues in the vein, listing all their running costs and conspicuous consumption before concluding “it did mean that if he didn’t get his million-pound bonus this year he was at genuine risk of going broke.”

Good grief. Arabella’s whole existence revolves around spending money – she doesn’t work, a nanny takes the kids out all day, (“Matya had no theories about children, she took them as she found them, but it seemed to her that many of the children she had looked after were both spoilt and neglected.”) she has no hobbies or interests and seems to define herself through what she owns, so Roger and Arabella’s entire lives pretty much rest on his bonus.

Meanwhile, someone is sending postcards to the residents of the street, which only say “We Want What You Have”. The campaign escalates and the various residents start to feel uneasy:

“the thought of other people wishing they had your level of material affluence was an idea you could sit in front of, like a hearth fire. But this wasn’t like that. This was more like having someone keeping an eye on you and secretly wishing you ill.”

Detective Inspector Mill is called in to investigate:

“His hair wasn’t in fact long enough to get into his eyes, but this gesture was like an atavistic survival of a period during which he had a long, floppy fringe. So for a moment everyone in the room glimpsed him with that languid public school hair.”

Underestimate this unlikely copper at your peril, though. Mill’s investigation forms the background mystery to the novel, but really this is a story about the variety of overlapping lives that take place in a typical London street: their hopes, triumphs, tragedies and the banal stuff in between. It’s a clever novel and extremely well-written, the pace doesn’t flag and I cared about all the characters (even a tiny bit about Arabella, who is clearly deeply unhappy and has no idea why). Unlike NW, there is one consistent authorial voice, but similarly to NW, Capital succeeds in capturing some of the complexity of a huge city and its many residents.

Capital was adapted into a 3-part BBC drama last year, starring the brilliant Toby Jones as Roger and a great turn by Rachel Stirling as the terrible Arabella: