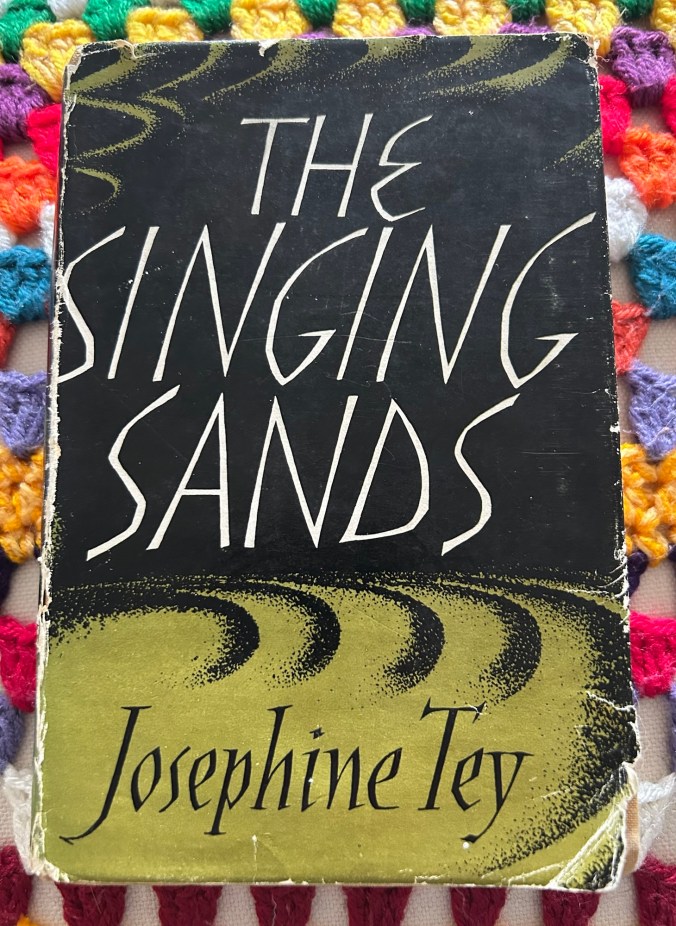

Today for the 1952 Club hosted by Kaggsy and Simon I’m looking at another golden age mystery. The Singing Sands by Josephine Tey features her regular detective, Inspector Alan Grant. It was found in her papers after she died and published posthumously, which usually makes my heart sink, but the novel seems pretty complete so I hope it was as she planned.

You can come across all sorts prejudices and snobberies in golden age crime and The Singing Sands has a strong one running throughout, which admittedly I’ve not encountered before in the genre: Tey is a total snob about Scotland. As far as I can work out her rules are:

- Be Scottish

- But speak with an English accent (by which I assume she means RP – I doubt my south London tones would cut the mustard)

- Don’t be from the city

- Especially don’t be from Glasgow

- Be from the Highlands

- Don’t be a nationalist

- Really don’t be from Glasgow

I take great exception to her attitude to Glasgow – it’s a beautiful city full of friendly people. Every time I go I’m knocked out and I’m still giving serious consideration to moving there. In the end when I came across these attitudes I just rolled my eyes and skipped on, and it didn’t affect my enjoyment of the novel. But as a counterbalance I urge everyone to (re)visit wonderful Glasgow!

On with the novel! It opens with Grant struggling with his mental health and deciding to visit his cousin Laura (Lalla) and her family in the Highlands to recuperate. The background of what led to Grant reaching this point is never quite specified but he seems to be experiencing burnout/PTSD.

As he disembarks the train, the grumpy attendant is trying to rouse the passenger in berth B Seven. Grant realises he is dead, and his interest in faces (detailed extensively in The Daughter of Time which is where the title quote comes from but would have worked very well in this novel too) is piqued:

“What would bring a dark, thin young man with reckless eyebrows and a passion for alcohol to the Highlands at the beginning of March?”

He also picks up B Seven’s newspaper, which has some cryptic verse scribbled on it. Much as Grant tries to focus on his family and the fishing expeditions he had planned, his mind keeps being drawn back to B Seven. The verse leads him to visit some of the islands to identify the landmarks mentioned:

“There was nothing else in all the world but the green torn sea and the sands. He stood there looking at it, and remembering that the nearest land was America. Not since he had stood in the North African desert had he known that uncanny feeling that is born of unlimited space. That feeling of human diminution.”

Although his colleagues in London have identified the body and ruled accidental death, Grant thinks both these conclusions are questionable. Despite trying to recover from his work, he can’t let it go. He is aware that keeping his mind occupied can be useful, but it is a fine balance:

“Grant was very conscious that his obsession with B Seven was an unreasonable thing; abnormal; that it was part of his illness. That in his sober mind he would not have thought a second time about B Seven. He resented his obsession and clung to it. It was at once his bane and his refuge.”

We follow Grant as he heals, with the help of his beautiful environment, the understanding of his family, and his pursuit of the truth.

“But for B Seven he would not be sitting above this sodden world feeling like a king. New born and self-owning. He was something more than B Seven’s champion now: he was his debtor. His servant.”

The Singing Sands is not heavily plot-driven and the mystery is slight, but it is still an enjoyable read, if a slightly unusual approach to the genre. Grant’s dogged pursuit of the truth of a death which others seem quick to disregard makes him endearing, and there are lovely descriptions of the Highlands. It’s a quick read that doesn’t outstay its welcome, and it is compassionate in its portrayal of mental health.

“In matters where A was at spot X at 5:30pm on the umpteenth inst, Grant’s mind worked with the tidiness of a calculating machine. But in an affair where motive was all, he sat back and let his mind loose on the problem. Presently, if he left it alone, it would throw up the pattern that he needed.”