Happy (belated) Valentine’s Day! In my post for Valentine’s Day last year (which was also late…) I pointed out that St Valentine is the patron saint for bee keepers, plague, epilepsy and against fainting, as well as for lovers. Last year I wrote on bee-keeping and plague but this year I’m going to be more romantic and tell you about the man in my life. He’s always been there, but these last few weeks it’s like I’m seeing him with new eyes; now I’m obsessed and we spend hours together every day. The title quote may have given it away: he’s Cary Grant.

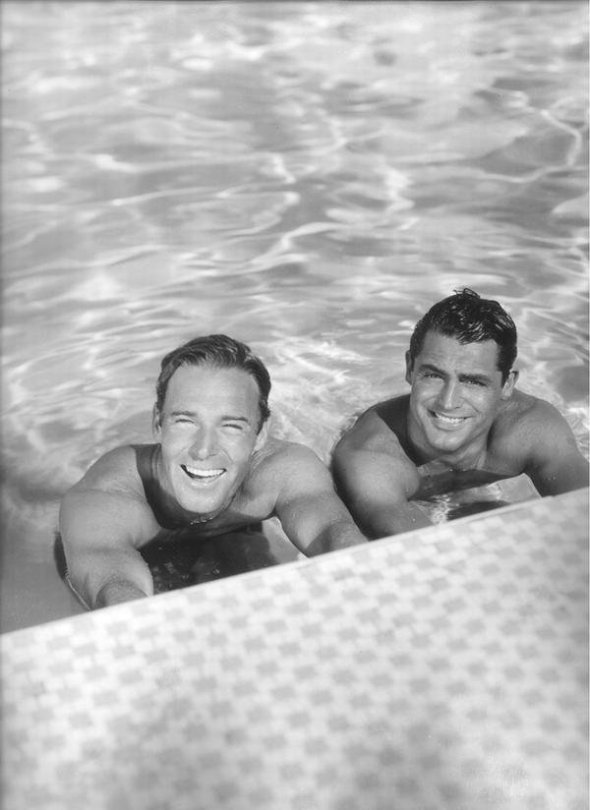

Let me explain. For my last paper before finals (FINALS! I’ve just broken out in a cold sweat….) we were given some optional papers to choose from, and I chose Film Criticism. We’ve been looking at Hollywood Golden Age, a genre Cary Grant sits astride like a tanned, debonair, mid-Atlantic-accented colossus. Having watched soooooo many of films again (and again, and again) I have a new-found appreciation for this actor with his exquisite comic timing. It’s not that I didn’t like him before, I just took him for (ahem) granted. This is how good he is: I had to analyse a scene from a film, and I chose something from Bringing Up Baby. It was 3 minutes 39 seconds long. I spent an entire day watching and re-watching the scene. Think about how many 3 minutes and 39 seconds there are in a day. That’s how many times I watched it. At the end of the day I was still laughing at his performance. The man is a genius. In the spirit of Valentine’s Day here he is with long-term boyfriend totally-platonic-friend-who-he-just-happened-to-live-with-for-twelve-years, Randolph Scott.

(Image from http://blogs.villagevoice.com/dailymusto/2010/09/cary_grant_and.php)

What a ridiculously good looking pair. Anyway, I thought for this post I would look at two of his favourite novels. According to IMDB he was a voracious reader. Do you think I can find out what he liked to read? Google, thou hast failed me. (Probably now I’ll be told that it’s really well-known that he loved Moby Dick or something, but I couldn’t find it). So instead I’ve chosen a James Bond novel as apparently the character was partly modelled on him and he was considered for the role in Dr No, and a short story by a writer who like Archie Leach was famous under a pseudonym.

Firstly, Casino Royale by Ian Fleming (1953). I’ll be honest, I went into this novel with very low expectations. Even the most avid Fleming fan will tell you that some of the novels are absolute bilge; apparently the quality of the Bond novels varies widely. This was the first Bond novel written and the first one I’d read, and I was pleasantly surprised. OK, Fleming isn’t a grand literary genius, but I doubt he ever proclaimed himself as such. Casino Royale is a decently written spy story. It’s quite different to the film, although similarities remain. I was expecting a flashy, superficial story but it’s a bit more reflective than that. It opens:

“The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling – a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension – becomes unbearable and the senses awake and revolt from it.”

Bond has been sent to Royale-le-Eaux to take down a Russian spy, Le Chiffre, by bankrupting him at gambling. This being the Cold War, of course the baddies are Russian, and there’s also the rather sinister SMERSH, a Russian covert group whose name means “death to spies” lurking in the background. That’s the very simple premise of the story. Along the way there are lingering descriptions of clothes, cars and food (Fleming was clearly something of a gourmand), but the presentation of Bond is more complex than I was expecting. I don’t think the reader is supposed to wholly like him or trust him:

“His last action was to slip his right hand under the pillow until it rested under the butt of the .38 Colt […] Then he slept, with the warmth and humour of his eyes extinguished, his features relapsed into a taciturn mask, ironical, brutal and cold.”

Bond is more human than in the films (he vomits in the gory aftermath of an explosion). He’s also damaged and flawed, more in keeping with the later filmic representations. Very much of its time, however, is the misogyny:

“These blithering women who thought they could do a man’s work. Why the hell couldn’t they stay at home and mind their pots and pans and stick to their frocks and gossip and leave men’s work to the men.”

As well as this general sexism, there’s also a worryingly easy conflation of sex with violence:

“Bond saw luck as a woman, to be softly wooed or brutally ravaged, never pandered to or pursued.”

Truly obnoxious and offensive. But in Fleming’s defence I would say that he seems more emotionally intelligent than his protagonist and we’re not supposed to see Bond as a role model in this sense. There’s also a good dose of humour in the novel which encourages us not to take Bond entirely as seriously as he takes himself:

“Englishmen are so odd. They are like a nest of Chinese boxes. It takes a very long time to get to the centre of them. When one gets there the result is unrewarding, but the process is instructive and entertaining.”

So, Casino Royale was better than I expected. It’s attitudes to women and Eastern Europeans are dated and offensive but as I said, I don’t get the sense the novel fully endorsed the attitude of its protagonist. It’s a quick, light read (although the descriptions of gambling dragged a bit in places) and for me it was good introduction to the Bond novels.

Secondly, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1867) by Mark Twain. What an irresistible title. Twain was a fairly prolific short story writer, but this was only the second one he wrote. You can read the full text of it here. It really is a very short tale, and shows how much can be done in so limited a space by an accomplished writer. It opens:

In compliance with the request of a friend of mine, who wrote me from the East, I called on good-natured, garrulous old Simon Wheeler, and inquired after my friend’s friend, Leonidas W. Smiley, as requested to do, and I hereunto append the result. I have a lurking suspicion that Leonidas W. Smiley is a myth; that my friend never knew such a personage; and that he only conjectured that, if I asked old Wheeler about him, it would remind him of his infamous Jim Smiley, and he would go to work and bore me nearly to death with some infernal reminiscence of him as long and tedious as it should be useless to me. If that was the design, it certainly succeeded.

As you can see, Twain’s humour is at the forefront (if you hadn’t already guessed by the title) and the mix of the ridiculous (“Leonidas W Smiley is a myth”) and the dry (“as long and tedious as it should be useless”) makes the story hugely entertaining. It’s certainly a confident writer who tells a tale he says will be tedious, and Twain does this not once but twice: “Simon Wheeler backed me into a corner and blockaded me there with his chair, and then sat me down and reeled off the monotonous narrative which follows this paragraph.” Simon Wheeler’s story of a gambling addict (Jim Smiley) who will bet on anything is directly reported, and he has one of the distinctive Southern voices Twain is so famed for, such as when he’s recounting how Jim trains the titular frog:

“He ketched a frog one day, and took him home, and said he cal’klated to edercate him; and so he never done nothing for three months but set in his back yard and learn that frog to jump. And you bet you he did learn him, too. He’d give him a little punch behind, and the next minute you’d see that frog whirling in the air like a doughnut see him turn one summerset, or may be a couple, if he got a good start, and come down flat-footed and all right, like a cat.”

There are some lovely touches in this story. I particularly liked the line: “Smiley said all a frog wanted was education” and the fact that the frog is endowed with the decidedly un-froggy full name of “Dan’l Webster”. A quick read that children and adults will enjoy.

To end, here is a clip from The Philadelphia Story, and just possibly the most charming 3 minutes and 46 seconds ever committed to celluloid. Apparently the bit where Cary Grant says “excuse me” was ad-libbed & that’s why he & James Stewart are trying not to laugh. Enjoy!