Being a Brit, I love talking about the weather. Seriously. I love the fact that it’s the usual conversation opener for the stranger next to you in the queue (another great British past time). I never tire of it. There’s always something to say. At the moment, that thing is: “Will this never end? I’m melting. I’m honestly melting. Look, my feet are fusing with the tarmac. Look.” Yes, we are having a heat wave. And my usual refrain in hot weather of “At least it’s not as bad as 2006” won’t work, because it is as bad as 2006. It’s too hot. I live in London. Over 30C is fine by the coast, but in a city that is ill-equipped to deal with it (there’s not exactly an abundance of air-conditioning; the Tube is like some sort of medieval torture oven masquerading as public transport; the shops are selling out of water, and people are leaving huge chunks of their own scorched skin in their wake) it’s truly revolting. We had respite of one blissfully grey day and then that blistering ball of fire was back in the sky. So I’m afraid there was only one choice for a theme for this week’s post, and it has to reflect my current obsession with all things meteorological (I’m checking the BBC weather pages every few hours in the delusional hope the forecast changes to gale-force winds and squally showers. Not that I know what squally showers are but I’m pretty sure I’d welcome them right now. Although last night there was a thunderstorm & all that’s done is make the humidity worse.) I’ve chosen two novels that use stifling hot weather to further the oppression felt by their protagonists. For those of you suffering a heat wave, I hope it helps in the way CS Lewis identified: “We read to know we are not alone.” For those of you in colder climes, I hope you feel a reflected warmth from the stories, you lucky, chilly people.

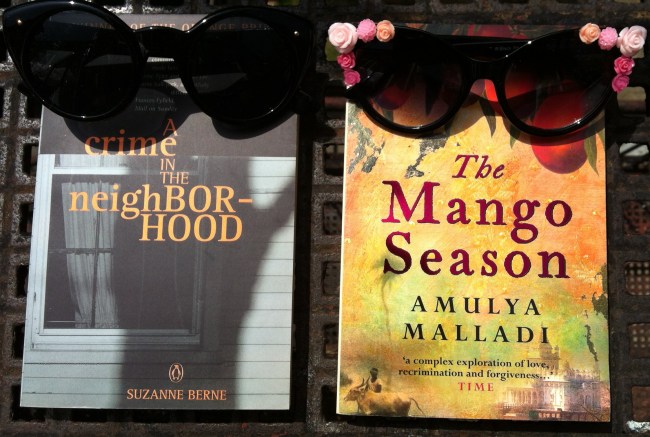

Firstly, A Crime in the Neighbourhood by Suzanne Berne (Penguin,1997). This was Suzanne Berne’s first book and was pretty well-hyped, winning the Orange Prize and being compared to To Kill a Mockingbird. I’m sure the comparisons were well-intentioned, but who can live up to that? To Kill a Mockingbird is about as perfect a piece of writing as you’ll come across. It’s hardly a major criticism if I say this isn’t as good; few books are. But A Crime in the Neighbourhood is still a well-written, atmospheric and insightful novel with plenty to say.

Set in 1972 with the Watergate scandal playing out in the background, 10-year-old Marsha tells the story of her suburban neighbourhood, where the body of a 12-year-old boy has been found, raped and strangled. Marsha has broken her ankle and so is somewhat confined, and her father has left the family for his wife’s sister. As both her family and the wider community try to deal with the acts of violence that have been perpetrated, Marsha watches and tries to make sense of it all.

“It had been wet in March and early April, then suddenly it got very hot. In just a few days, our big front yard went from a brown mat to a seething tangle of colour […] Blooming saturated the air, seeping in through open windows and under doors and into the sofa’s upholstery […] A kind of lawlessness infected everything. Next door, eight-year-old Luann Lauder decorated herself with toothpaste one Sunday morning and ran across the lawn in only her underpants. Boyd Ellison appeared on the playground one afternoon with a ten-speed bicycle he said was a birthday present but which looked just like our neighbour David Bridgeman’s bicycle, which had recently been stolen. Blue jays screamed all day long. Even the grass looked unearthly green, as it does right before an electrical storm, when the air starts to hum and your hair stands on end. And yet our neighbourhood was anything but lawless.”

The atmosphere in the neighbourhood becomes stifling both physically and psychologically. Berne creates a sense of things quietly building towards a denouement, but not an outcome that can be trusted to bring resolution (we know from the start that the boy’s killer is never found). When Marsha’s mother says “I sometimes think the suburbs are a distortion.” she picks up on the way human beings can warp what they see when emotions are heightened, and how dangerous this can be when it happens as a group. Within this atmosphere, Marsha builds her notebook of Evidence:

“Among the details I overheard from my post on the porch, all of which I printed in my notebook with Julie’s Bic pen, are the following: Boyd Ellison was alive and had told the police everything. A man on a motorcycle had attacked him. A man with a beard attacked him. It was a bearded man with a foreign accent, maybe Dutch or Turkish. It was a hippie on drugs. Boyd was in a coma. Boyd had called out his mother’s name. He didn’t know who his parents were. He was dead. He was alive. He was alive but just barely. He was dead.”

Marsha’s distortions will have a cataclysmic effect when she decides to voice them. Although taking a single crime in the neighbourhood as its starting point, the novel actually concerns itself with many types of violence human beings can enact on each other, almost with indifference. However, the tone is realistic rather than downbeat, and so the novel is thought-provoking without being depressing.

A very different tale takes place within the sultry weather of The Mango Season by Amulya Malladi. Now, this is a slight departure for me because generally I’ll only write about books I really rate, whereas I think The Mango Season is…OK. It’s not a terrible book by any stretch, but it’s quite pedestrian in its language and the story is somewhat slight. However, I decided I would write about it as generally “summer reads” are usually something light by definition, nothing too taxing while you’re roasting your body by the pool. And as a summer read The Mango Season fits the bill fine. Priya is living in the US, engaged to an American. She returns home to India to meet her family for the first time in seven years, to try and deal with the fact that they want to arrange a marriage for her. She returns in mango season, the hottest time of year:

“It was overpowering, the smell of mangoes – some fresh, some old, some rotten. With a large empty coconut straw basket, I followed my mother as she stopped at every stall in the massive mango bazaar. They had to taste a certain way; they had to be sour and they had to be mangoes that would not turn sweet when ripened. The mangoes that went into making mango pickle were special mangoes. It was important to use your senses to pick the right batch.”

The story plays out as you’d expect – Priya struggles to adjust to being back at home and the differences between America and India, and between her and her family. This is a light book and the dramas play out comfortably, The Mango Season is a comforting read. Malladi writes about India evocatively and with affection:

“Yellow and black auto rickshaws drove noisily on the thin, broken, asphalt road as I walked on the dirty roadside, sidestepping around rotten banana peels and other unidentified trash. […] I stopped in front of a small paan and bidi shop where they sold soda, cigarettes, bidis, paan, chewing gum and black market porn magazines, the covers of which you could only see through shiny plastic wrappers. They were hidden, but not completely; you could once in a while catch a naked thigh or dark nipple thrusting against the plastic wrap. A man sat in a hole in the wall and looked at me questioningly.

“Goli soda hai?” I asked.”

The Mango Season is a pleasant read, and when it’s this hot, that’s enough.

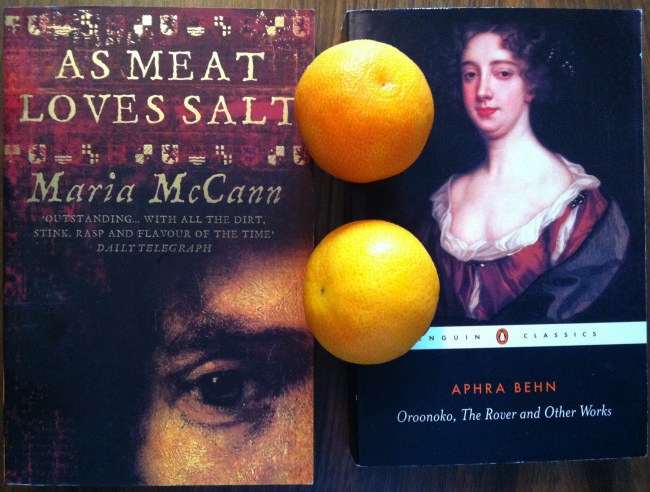

Here are the books basking: