I’m hopelessly late with this post, which was prompted by 17 May being the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia. At first when I was looking at what was going on this past week for a theme for this post, I was resistant to choose this, as it seemed I would be attaching the potentially reductive label of “gay writing” to literature. I’m not sure about this label for the same reason I’m unsure of the label “women’s writing” – while not necessarily inaccurate, it seems to suggest its somehow not “proper” writing, that it can only appeal to ready-designated group and have no meaning outside of that. Well, to quote Maya Angelou, we are all more alike than we are unalike, and so great writing is great writing. Who a writer chooses to sleep with is their own business, and if this informs their writing I don’t see why it should be picked out as “gay writing” unless we have the label “straight writing” which, of course, we don’t. And I guess that’s my main objection. There’s nothing inherently wrong with literature being labelled as gay, except that because the sexuality is marked out when straight isn’t, it seems to be suggesting a deviation from some sort of norm. And as Dorothy Parker pointed out….. So why did I decide to go ahead with it? Because we still need an International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia, because the city I live in has seen a rise in homophobic attacks over recent years, because this sickening hate crime still exists, and so I wanted to recognise 17 May as an important day. I hope one day it is no longer needed. And now I’ll climb down off my soapbox to talk about books, no more ranting, I promise…

Firstly, Tipping the Velvet by Sarah Waters (who doesn’t mind being labelled a lesbian writer, so maybe I should stop being quite so precious about it) (1998, Virago). This was Sarah Waters’ first novel and was widely well received; she has gone on to forge a successful literary career with four further novels. I enjoy her work greatly, because she writes evocatively of the past (in TtV its Victorian London) and is a beautiful writer who also has a great command of plot. The plot of TtV sees Nan King fall in love with a male impersonator, Kitty, and she leaves her home and family to work with Kitty in the theatres and music halls. They begin a relationship, but when this disintegrates Nan leaves her and works in London, selling her body as a boy, becoming a rich woman’s plaything, and getting caught up in politics through her friendship with a neighbour.

“The Palace was a small and, I suspect, a rather shabby theatre; but when I see it in my memories I see it still with my oyster-girl’s eyes – I see the mirror-glass which lined the walls, and the crimson plush upon the seats, the plaster cupids, painted gold, which swooped above the curtain. Like our oyster-house, it had its own particular scent – the scent, I know now, of music halls everywhere – the scent of wood and grease-paint and spilling beer, of gas and of tobacco and of hair-oil, all combined.”

Waters often describes settings through smells, and it is a technique that works well, creating a vivid earthiness that engages with Victorian literary tradition but pushes far beyond it, giving a voice to those largely unheard in the literature of the time:

““You say I know nothing about you; but I have watched you upon the streets, remember. How coolly you pose and wander and flirt! Did you think you could play at Ganymede , for ever? Did you think, if you wore a silken cock, it meant you never had a cunt at the seam of your drawers?….You’re like me: you have shown it, you are showing it now! It is your own sex for which you really hunger!””

“Tipping the velvet” is Victorian slang for cunnilingus, something I don’t remember occurring in Dickens…

Secondly, The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891, my copy 1994). I won’t go into this in great detail, because I think it’s one of those novels that everyone knows even if they haven’t read it. A beautiful boy named Dorian Gray has his portrait painted, capturing his first flush of youth. Under the influence of the hedonist Lord Henry Wotton, Dorian offers up his soul to stay beautiful forever. He gets his wish, and the portrait ages in his place, growing more hideous with each passing year as a reflection of Dorian’s corrupted soul. This was Oscar Wilde’s only novel and was hugely controversial at the time, but as my plot summary has hopefully captured, it’s actually a highly moral work. It’s also gorgeously written, with Wilde bringing his aesthetic sensibilities to his prose, and full of typically Wildean aphorisms to raise a smile amongst the dark subject matter:

“You have a wonderfully beautiful face, Mr. Gray. Don’t frown. You have. And beauty is a form of genius -is higher, indeed, than genius, as it needs no explanation. It is of the great facts of the world, like sunlight, or spring-time, or the reflection in dark waters of that silver shell we call the moon. It cannot be questioned. It has its divine right of sovereignty. It makes princes of those who have it….. People say sometimes that beauty is only superficial. That may be so, but at least it is not so superficial as thought is. To me, beauty is the wonder of wonders. It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.”

TPoDG is a great read, with something for everyone: wit, morality, amorality, the Gothic, adventure, and almost pastoral in places with its detailed descriptions of nature. It also, like Dorian, hasn’t aged one jot. In this age of celebrity obsession focussed so much on appearances, the enormity of the cosmetics industry, of plastic surgery and of so much style over so little substance, TPoDG has as much to say about our society today as it did about late Victorian society. We all have to face our portraits at some time…

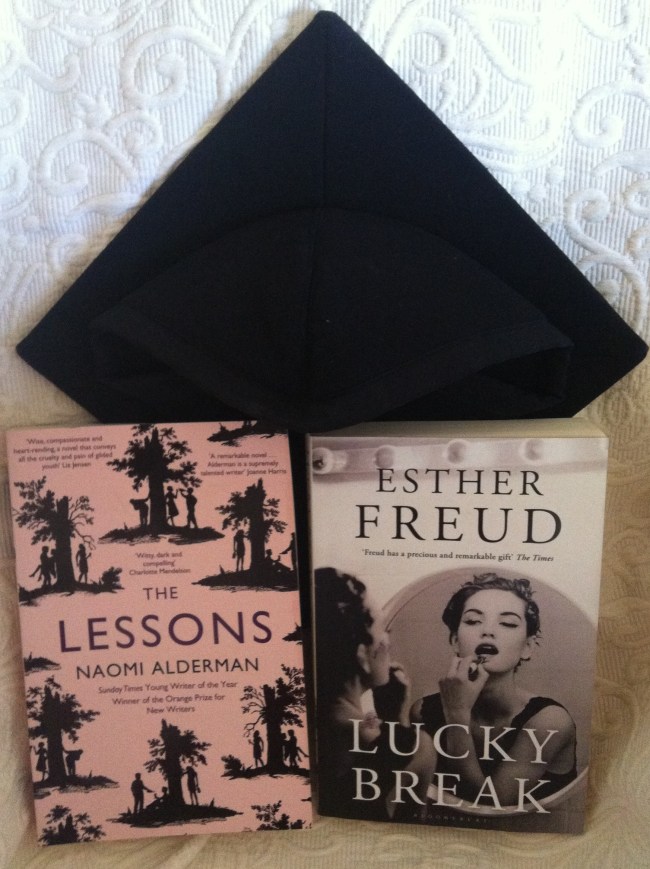

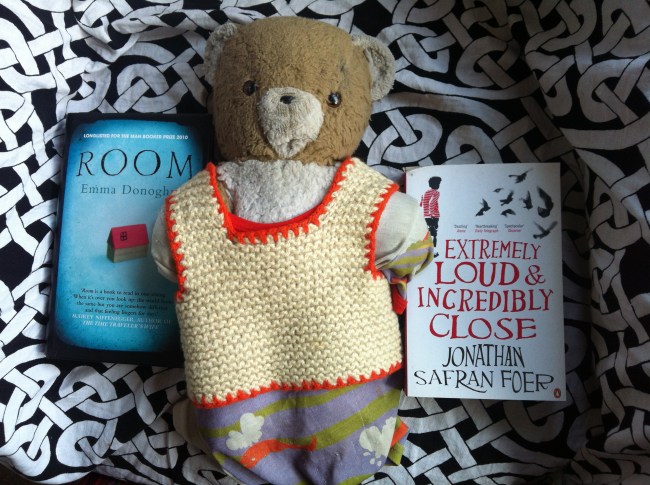

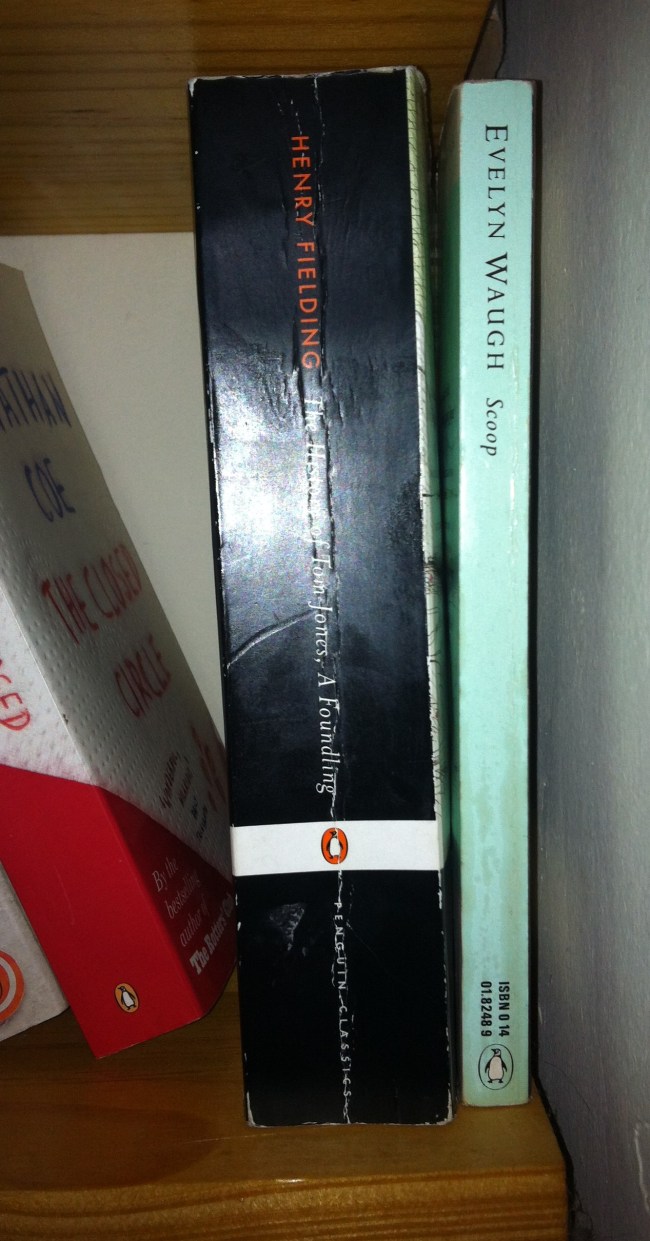

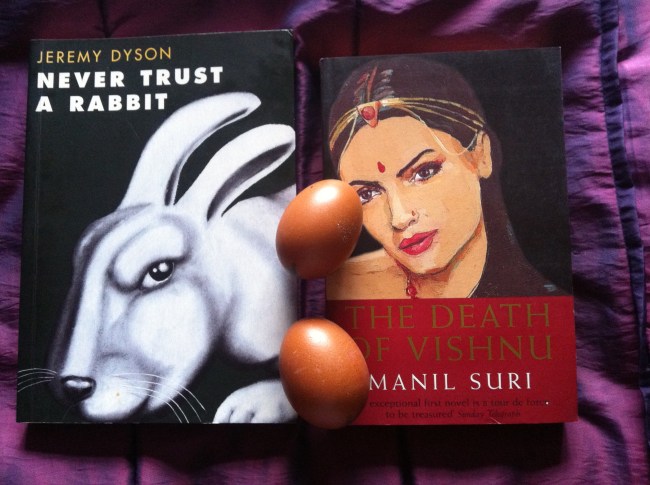

Here are the novels wearing a rainbow, symbol of LGBT Pride (and surrounded by cat hair, sorry about that):