“We all know families who are poor but ‘respectable’. Mine, in contrast, was extremely rich but not ‘respectable’ at all.”

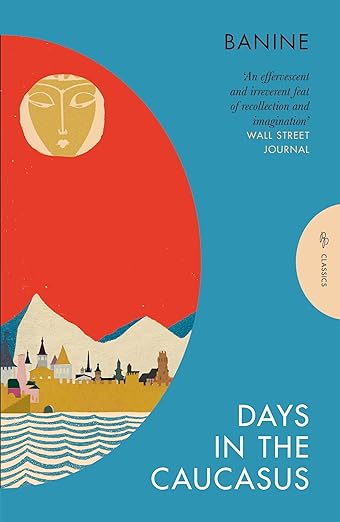

I don’t often write about memoir on the blog, but Days in the Caucasus by Banine (1945, transl. Anne Thompson-Ahmadova 2019) was just irresistible. Detailing her childhood in Baku, capital city of Azerbaijan, it is the next stop in my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge, and my final read for this month’s #ReadIndies, hosted by Kaggsy.

Banine’s style is energetic, direct and engaging. Although chronological, she doesn’t attempt to capture a full picture of her life, but rather a patchwork of people, places and events. It reads like a novel, and this description of her relationship to inanimate objects as a very small child gives an indication of the writer who would emerge:

“But not many people understood it, and when Fräulein Anna caught me in conversation with a tree or bench, she would take exception and threaten me with punishment. ‘What for?’ I would ask in surprise. Adults’ blindness towards my world seemed to me a fundamental injustice.”

Her family were farmers who made a lot of money unexpectedly in oil. This has caused tension as her father and his brother have disagreed about how the inherited wealth has subsequently been distributed:

“[Uncle Suleyman] let his wife live with us, on the sole condition that she had the occasional row with my father.”

Banine has never known it to be different, and her imperious grandmother rules over their privilege with a rod of iron:

“Like Louis XIV she found it practical to spend much of her time on a commode, a jug for ablutions within reach. Sitting regally on this throne, she received her supplicants, including men.”

“She was highly suspicious of any country outside of circumference of fifty kilometres. Once past the fifty-kilometre mark they were all equally far away—France, Crimea, America or Batumi.”

However, the world will soon impose on their way of life. Banine lives through the Russian Revolution and the invasion of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. As a teenager, she is torn between her Islamic upbringing and Communism, specifically, falling in love with a Bolshevik while the family arrange her marriage to a man she despises.

“I didn’t know that a long, hard war and a long, hard revolution would one day open up to me the land of my most cherished dreams. No, I knew none of this then. I was preparing for a very different life that I thought I already knew.”

Her cousin Gulnar is more rebellious and unashamed of her considerable drives, announcing to her much more innocent cousin:

“It can’t be as much fun to write a novel as to live one.”

The politics don’t detract from Banine’s love of family and love of her land though. I enjoyed this description of female-only hammam parties:

“The dense steam went to their heads like wine. Between washing their hair and depilating their thighs, they would on occasion be bold enough to arrange a marriage, which only increased the prestige and renown of the hammam parties.”

And her uncle’s whimsical home:

“The house had an inner courtyard for elephants (who never did take up residence) and a roof where jasmine could grow (but never did).”

Eventually though, the family have to decide whether to stay or go as they will not be able to continue the lives they are used to under Russian occupation:

“Uncle Suleyman had, therefore, decided to ‘escape’. This heroic verb pleased him greatly: he conjugated it with sensual delight, repeated it with satisfaction all day long, artfully using it to impress his audience.”

Days in the Caucasus captures a time of great upheaval and change, both personally and politically for the young Banine. War, Turkish occupation, British occupation, establishment of the ADR, then Russian occupation. But even for those of us that haven’t lived through such immense events, she remains recognisable and relatable as she struggles find her place in her family, her culture and society.

Banine is such an endearing narrator too: unsentimental, loving, and funny. I’m looking forward to catching up with her in her second memoir Parisian Days, also published by Pushkin.

“Who can tell the importance of dreaming? And of reading!”