Today is the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act in Britain receiving Royal Assent, which enabled all men and some women over the age of 30 to vote for the first time (it would be another 10 years before women got equal voting rights). There are lots of events going on this year to commemorate the centenary, but it’s also worth noting that the suffragettes argued for equal pay for equal work, and yet 100 years later (last week) Carrie Gracie has been giving evidence to MPs over pay discrimination at the BBC. This is just one example. The fight for equal rights worldwide is ongoing.

For this post I’ve picked one novel written by a suffragette and a short story from the twentieth-first century portraying suffragettes.

Firstly, No Surrender by Constance Maud (1911), who was a member of the Women Writers Suffrage League. I read a crusty copy from the library which had that pleasing old book smell, but Persephone have published it as one of their beautiful editions too, and if you’re on a book-buying ban like me, they also offer it as a free e-book.

Maud looks at suffrage primarily through the story of young cotton mill worker Jenny Clegg. Jenny Clegg’s father has all the power in their home while her mother does all the work:

“Her voice took on its usual apologetic tone with her lord and master. For Mrs Clegg was imbued with a spirit of such humility that she apologised not only for rising early and late taking rest, while fulfilling her manifold obligations towards her mate, such as bearing and raising his ten children, cooking, washing, mending, cleaning for the family, but even for her very existence up to the age of fifty-five in this strenuous service without pay.”

Mr Clegg squanders the money earned by the women in his family such as Jenny. He is selfish but supported by law and society in his behaviour:

“Mr Clegg regarded his daughter sternly, but without wrath. He answered her in measured tones, strong in his sense of his impregnable position, backed as he felt himself to be, not only by the law of the land, the tradition of generations, his own physical force and intrinsic superiority of sex, but by the innermost conviction and consent of all right-thinking womankind.”

Jenny’s political awareness is given direction when she encounters Mary O’Neil, a moneyed society girl who rebels against her class’ expectations of her and supports the suffragettes. There is humour in her mother’s friend Lady Walker’s attitudes towards her own gender:

“ ‘Can you suppose for one moment that a man like Horace Boulder, or even Penhaven, would have been attracted, had Helen or Cicely shown a tendency to independent interests and original thought?’ “

There were plenty of women against the suffragettes, and Lady Walker’s dismissal of them as “ ‘hysterical, unsexed creatures, with a mania against men.’” was not unusual. The character provides some much needed levity, but is never presented as ridiculous, as this internalised misogyny had a major impact on the lives of women at the time, helping maintain the limitations of their rights and freedoms.

Maud covers the main events of the movement up until that time, and uses various scenarios to get across the arguments of women’s suffrage: speeches from carriages, dinner party conversations, arguments between lovers. This is both the strength and weakness of the novel. No Surrender is an issue-lead novel, despite Maud placing a romance between Jenny and Joe Hopton, Labour party candidate, as the driving plot. As such, it sometimes falters under the weight of its intentions. Much as I dislike Dickens, he is an absolute master at dramatising his social commentary. Maud is not so gifted and sometimes No Surrender is overly didactic, with poorly realised characters and a sentimental tone. But I must stress that this is not all it is. It is also able to dramatise how:

“Courage, self-abnegation, forethought, invention, and a keen sense of humour marked the tactics of the militant movement.”

bringing a unique, personal perspective to balance the reportage (and lack thereof) regarding the movement. While at times I found the characterisation of the working classes a bit ‘gor blimey guv’nor’ (or perhaps I should say ‘ee by gum’ as its northern stereotypes) it’s still commendable that Maud roots the story in the working classes, and shifts the focus from the middle class suffragettes.

“’there’s a good many ladies who’d be doin’ far more good in the world if they thought more about their womanhood and less about their ladyhood’”

So all in all, a flawed novel but a fascinating one, written contemporaneous to the movement by someone who was directly involved.

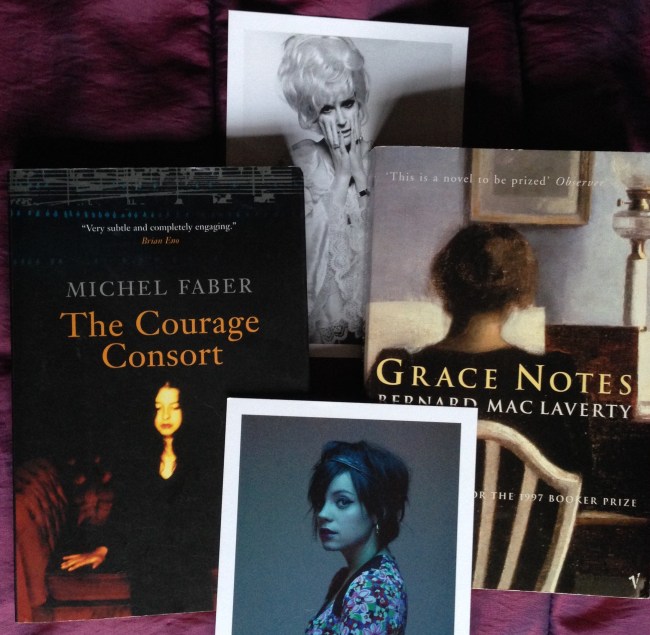

Secondly, A Mighty Horde of Women in Very Big Hats, Advancing, the final and longest story in the short story collection The Apple by Michel Faber (2006), in which he revisits the characters and setting of his hugely successful novel The Crimson Petal and the White. I’m going to ignore the links to TCPATW to avoid spoilers for those who haven’t read it (it’s great – you should definitely read it!)

The story is narrated by an elderly man in a nursing home in the 1990s, recalling his life when he was very young, with his artist father, bohemian mother, and Aunt Primrose (who dresses in men’s clothes and shares a bed with his mother, but the menage a tois arrangement is never explicitly stated).

“You know, because I was a child in what’s now called the Edwardian era, and because I was born the day Queen Victoria died, I always think of the Edwardians as children. Children who lost their mother, but were too young to realise she was gone, and therefore played on as before, only gradually noticing, out of the corners of their eyes, the flickering shadows outside their sunny nursery. Shadows of commotion, of unrest. Sounds of argument, of protest, of Mother’s things being tossed into boxes, of fixtures being forcibly unscrewed, of the whole house being dismantled.”

Amongst this change, there is a conflict between old and new which is obvious to the small child on a daily basis:

“Bureaucrats, tradesmen, doctors, postmen, parsons, waiters, porters, the whole pack of them; they ignored my mother and Aunt Primrose, and directed their remarks to my father.”

But he is a preoccupied artist and it is the women who drive the lives of the household, with energy, fun, and strong political convictions:

“She an Aunt Primrose worked as a kind of music hall duo, Mama getting by on charm and disarming honesty, while Aunt Primrose supplied the sardonic touch. My father was – if you’ll excuse what’s definitely not meant as a pun – the straight man.”

The story culminates on Women’s Sunday, the Hyde Park rally of 21 June 1908 which was the first major meeting organised by the WSPU. A Mighty Horde of Women in Very Big Hats, Advancing covers a great many themes in its 60-plus pages: being part of stories we can’t fully comprehend, the flawed nature of memory, how history is made, the need to attach a narrative to our lives looking back. Faber is a brilliant storyteller, able to cover all this within a driving plot, authentic voice and lightness of touch. He’s said he won’t write any more since publishing Undying in 2016 following the death of his wife, and I sincerely hope he changes his mind. All the stories in The Apple were highly readable, they worked individually, as a whole, and as a sort-of sequel to TCPATW. He’s a great writer.

To end, a silly portrait of a suffragette but not one I can dismiss because it was probably the first time I learnt what a suffragette was: