Today’s post is the latest in a series of occasional posts where I look at works from Le Monde’s 100 Books of the Century. Please see the separate page (link at the top) for the full list of books and an explanation of why I would do such a thing.

A Room of One’s Own grew out of lectures Virginia Woolf was asked to give at Newnham and Girton Colleges, Cambridge, in 1928. You can read the full essay in various places online. Women were only officially admitted to the university in 1948, and the fact that these talks were given 20 years previously shows just how ground-breaking Woolf was. A Room of One’s Own is a vital proto-feminist text that remains relevant today. The fact that you can buy bags, pillows, tea towels, deckchairs, mugs, notebooks ad infinitum with the book cover on is an indicator of how much the central image continues to speak to people, as well as the arguments themselves.

(Image from: https://www.pinterest.com/particularbooks/postcards-from/)

The central image is: “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” In other words, she needs a means to support herself, and space to reflect and think; she needs liberty, and these things have been traditionally denied to women. They have been dependent on the men in their family for financial support, and not supposed to concern their pretty little heads with intellectual endeavour. Woolf argues her points forcefully but wittily, you never feel you are being bludgeoned by polemic. Take for example the opening paragraph:

“But, you may say, we asked you to speak about women and fiction – what, has that got to do with a room of one’s own? I will try to explain. When you asked me to speak about women and fiction I sat down on the banks of a river and began to wonder what the words meant. They might mean simply a few remarks about Fanny Burney; a few more about Jane Austen; a tribute to the Brontës and a sketch of Haworth Parsonage under snow; some witticisms if possible about Miss Mitford; a respectful allusion to George Eliot; a reference to Mrs Gaskell and one would have done.”

The paucity of women writers Woolf has at her disposal to refer to speaks volumes about the male dominance of writing up to this point, and the reliance on male point of view for literary portrayals of women:

“women have burnt like beacons in all the works of all the poets from the beginning of time — Clytemnestra, Antigone, Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, Phedre, Cressida, Rosalind, Desdemona, the Duchess of Malfi, among the dramatists; then among the prose writers: Millamant, Clarissa, Becky Sharp, Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary, Madame de Guermantes … Indeed, if woman had no existence save in the fiction written by men, one would imagine her a person of the utmost importance; very various; heroic and mean; splendid and sordid; infinitely beautiful and hideous in the extreme; as great as a man, some think even greater.”

Of course, Woolf was a highly accomplished and inventive writer herself, and this is reflected in the lecture which is not traditionally academic but instead illustrated with fictional characters such as Judith Shakespeare, sister of the more famous William:

“his extraordinarily gifted sister, let us suppose, remained at home. She was as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world as he was. But she was not sent to school. She had no chance of learning grammar and logic, let alone of reading Horace and Virgil. She picked up a book now and then, one of her brother’s perhaps, and read a few pages. But then her parents came in and told her to mend the stockings or mind the stew and not moon about with books and papers. […]She had the quickest fancy, a gift like her brother’s, for the tune of words. Like him, she had a taste for the theatre. She stood at the stage door; she wanted to act, she said. Men laughed in her face […]who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body? [She] killed herself one winter’s night and lies buried at some cross-roads where the omnibuses now stop outside the Elephant and Castle.”

As my extensive quoting shows, I think this is a fantastic essay, well worth reading. It isn’t flawless, it’s culturally biased towards the speaker and her audience: middle-class, white, Western women. But Woolf never claims to have all the answers: “women and fiction remain, so far as I am concerned, unsolved problems.” (I think the idea of women as an unresolved problem is ironic and assertive, not derogatory?) A Room of One’s Own highlights enduring problems, relevant to both genders, of how to claim societal freedom that will permit individual voices to be heard. It also makes me very glad that I am a woman in this day and age; I may be embarrassed at how ridiculously over-educated I am (a perennial student) but at least I had the choice to become so.

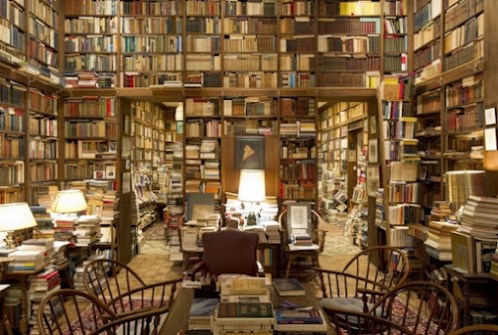

To end, a picture of a room I wish was my own – it could do with a few more books, though…

(Image from http://pawilson.ca/are-there-some-books-you-keep-reading-over-and-over/ )