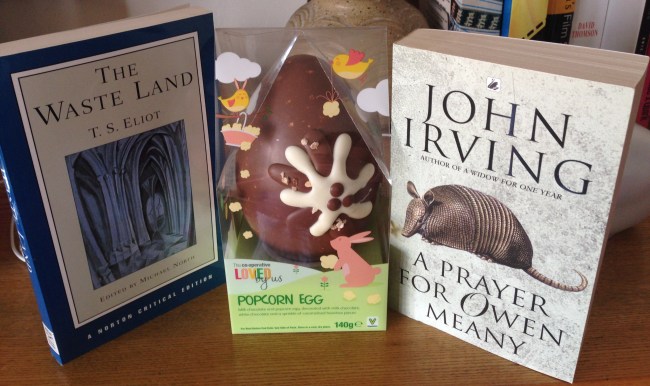

This is the second half of a challenge looking at the 10 Most Influential Books in your life. It was started by Leah at The Perks of Being a Bookworm and I was tagged by Emma over at A Wordless Blogger. Do check out their blogs and the other people taking part, it’s a fascinating challenge!

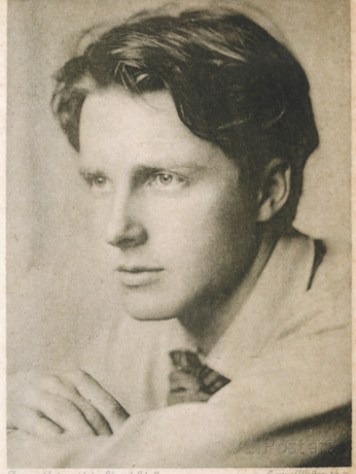

An Evil Cradling – Brian Keenan

Where to begin explaining this book? I’m going to sound ridiculous, but I can’t think how else to say it: this is one of the most moving, deeply profound books I’ve ever read, and it’s about what it is to be human. I’m sorry to sound so hyperbolic, but it really is that extraordinary. I wept throughout the whole thing. Brian Keenan was kidnapped in Beirut and held hostage for just under 5 years, some of it with John McCarthy. This book is an exploration of what he went through, and it’s just incredible. It’s not a journalistic, factual account, although Keenan grounds the story in this type of detail. It is much more a study of a human being in extremis. If I had to quote from this book I’d never stop, so instead I googled and chose what seemed to be the most popular:

“Hostage is a man hanging by his fingernails over the edge of chaos, feeling his fingers slowly straightening. Hostage is the humiliating stripping away of every sense and fibre of body and mind and spirit that make us what we are. Hostage is a mutant creation filled with fear, self-loathing, guilt and death-wishing. But he is a man, a rare, unique and beautiful creation of which these things are no part.”

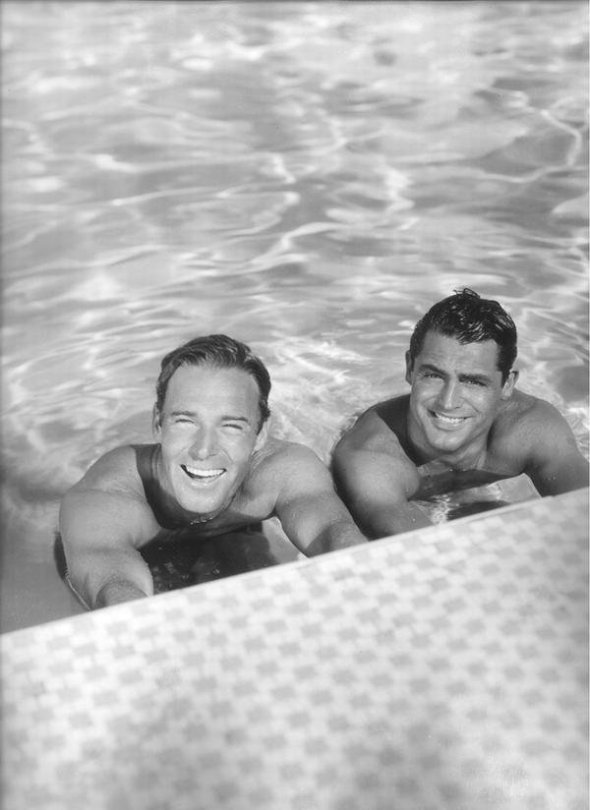

The Keenan/McCarthy story was filmed as Blind Flight. The film isn’t a patch on An Evil Cradling, but it features superb performances from Ian Hart as Brian Keenan and Linus Roache as John McCarthy:

The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tiler – Gene Kemp

(Image from: http://www.fantasticfiction.co.uk/k/gene-kemp/turbulent-term-of-tyke-tiler.htm)

When I was seven, I’d read all the books in our classroom, and so my teacher sent me to another class to borrow books from there. I was intimidated, the kids in that class were bigger than me, and the teacher was strict. She was also kind and fair, and did she know her children’s literature. She gave me loads of great books to read, and used to ask me what I thought about them. This was one of the first she gave me, and I think it stands out because it was when I started to read children’s books that were written primarily not to teach you to read, but for the joy of reading. It’s aimed at late junior school age, and tells the story of Tyke and Danny, in their final year of Cricklepit School. Tyke and Danny aren’t exactly naughty, but neither do they fit the teachers’ ideals of how pupils should behave. It’s a touching story of friendship, following your own beliefs, and not always obeying all the rules. Worthwhile lessons, it seems to me.

“That child has always appeared to me to be on the brink of wrecking this school, and as far as I can see, has, at last, succeeded.”

The Secret Garden – Frances Hodgson Burnett

(Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Secret_Garden)

This book followed me throughout childhood. I had the Ladybird version, and then when I was old enough my mother bought me the full-length original. As a child I found the story of spoilt Mary Lennox discovering a locked garden and turning it into a paradise again with the help of her friends really magical, but throughout my adult life I’ve noticed this book has a far reaching influence. On a very basic level, I love gardening, and when I picture my perfect garden it’s always walled; my horticultural ideal carried from this novel. But more than that, I think an interest in Victorian literature (although this book is strictly speaking Edwardian) and the Gothic can be traced back to this book. Big house, mysterious noises, servants denying all knowledge, death a constant threat, time spent roaming around on moors – sound familiar? If you want your child to embrace the Brontes, Wilkie Collins, Mary Shelley… start them off on The Secret Garden. But mostly I think this novel influenced my choice of career. I became an occupational therapist. The Secret Garden features a young boy, Colin, who is depressed, and constantly ill and weak. He meets his cousin Mary, they work together in the garden (what we in the trade call meaningful occupation) and Colin’s mental health improves alongside his physical health. So there you go: The Secret Garden is really all about the holistic health benefits of an individually tailored rehab programme.

“At first people refuse to believe that a strange new thing can be done, then they begin to hope it can be done, then they see it can be done–then it is done and all the world wonders why it was not done centuries ago.”

The Temple – George Herbert

This collection of poems is a lesson to me to keep an open mind. It’s resolutely religious, and I am not. You’d think I’d get nothing out of it, but George Herbert has become one of my favourite poets. I discovered him in a Renaissance literature class. We’d just had 2 weeks of John Donne: sexy, naughty, clever, complicated Donne. Now it was time for George Herbert. Not sexy, not naughty. Hugely clever, but written in a very simple style. I loved his gentle tone, his worry of not being good enough and his search for peace and solace. Herbert showed me that while beliefs are different, a common ground of experience and feeling can always be found. And maybe he’s sexier than he first appears: my tutor is convinced the penultimate line of this poem is a blow-job joke. It’s always the quiet ones….

Love III

Love bade me welcome, yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-ey’d Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

“A guest,” I answer’d, “worthy to be here”;

Love said, “You shall be he.”

“I, the unkind, the ungrateful? ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.”

Love took my hand and smiling did reply,

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Truth, Lord, but I have marr’d them; let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.”

“And know you not,” says Love, “who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

“You must sit down,” says Love, “and taste my meat.”

So I did sit and eat.

Sexing the Cherry – Jeanette Winterson

(Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexing_the_Cherry)

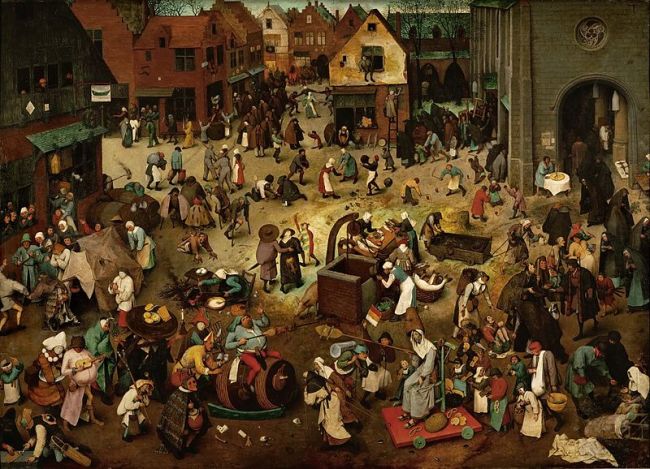

If I had to recommend a Jeanette Winterson novel, I’d most likely choose Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, which is probably why I’ve blogged on it in the past. Oranges is her most accessible novel, her most famous, and it is brilliantly written. The Passion I believe to be her best novel. However, I’ve chosen Sexing the Cherry as more influential on me, as it was my first foray into magic realism (although Jeanette Winterson rejects that term) and opened my eyes to what fiction can do. If it wasn’t for Sexing the Cherry, maybe I wouldn’t have discovered Angela Carter, or Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Set mainly in the seventeenth century, it tells the story of Jordan, orphaned and found floating in the Thames, and his companion, Dog Woman, a gross figure in both adjectival senses, as they journey together around London and across time. Sexing the Cherry challenges notions of outsider status, showing that there are few fixities by which to claim any sort of norm.

“Language always betrays us, tells the truth when we want to lie, and dissolves into formlessness when we would most like to be precise.”

So there it is, the 10 books that have most influenced me….so far. Here’s to discovering new influences and making time to revisit the old ones!

I’m not tagging anyone, or I’m tagging everyone, depending on how you look at it. If you’d like to take part please consider yourself tagged, and don’t forget to refer back to Leah’s blog when you write your post.