I’m starting to write this post at 7pm on the final day of the1956 Club, hosted by Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Simon at Stuck in a Book. There used to be a time when I wrote my Club posts in advance of the week, so it’s fair to say my blogging still hasn’t quite got back on track yet😊

Unusually for this blog, my first read is a non-fiction work, My Dog Tulip by JR Ackerley, a book which took me by surprise. The blurb on the back of my NYRB Classics edition describes it thus:

“The distinguished British man of letters J. R. Ackerley hardly thought of himself as a dog lover when, well into middle age, he came into possession of a German shepherd […] she turned out to be the love of his life […] a bittersweet retrospective account of their sixteen-year companionship, as well as a profound and subtle meditation on the strangeness that lies at the heart of all relationships. In vivid and sometimes startling detail, Ackerley tells of Tulip’s often erratic behavior and very canine tastes, and of his own fumbling but determined efforts to ensure for her an existence of perfect happiness.”

So basically I was expecting a period piece Marley and Me. The trailer for the 2010 film did nothing to dissuade me of this:

Yet my experience of reading this was of a deeply eccentric and sometimes quite unnerving narrative. I didn’t dislike it, but it just wasn’t what I expected at all. I should have paid more attention to the use of ‘strangeness’ and ‘startling’ in the blurb. I think Ackerley was probably quite an independent thinker and so he writes about Tulip in really quite astonishing ways. He clearly adores his dog and captures her in almost poetic blazon style:

“these dark markings symmetrically divide up her face into zones of pale pastel colours, like a mosaic, or a stained glass window; her skull, bisected by the thread, is two primrose pools, the centre of her face light grey, the bridge of her nose above the long, black lips fawn, her cheeks white, and upon each a patte de mouche has been tastefully set.”

That’s lovely, but for much of the book Ackerley is quite determined to Tulip mated and pregnant, and I could have done without similar dwelling on the state of her vulva. I’m not a prude, and my job means I spend most of each day talking about human anatomy in very frank terms, but I was truly taken aback.

I guess if you have a pedigree dog you do have to concern yourself with such things? Every animal I’ve had has been resolutely mongrel and neutered/spayed and therefore unable to pass on their moggy/mutt genes 😊

Being an animal lover I am used to vet visits, but this book made me very glad I’m not taking my furry family members to the vets in the 1950s. The beginning of the book describes some truly distressing experiences and I am so grateful times have changed. Ackerley shares this view and can’t believe what is happening, until he and Tulip meet the lovely Miss Canvey. Tulip is untrained and appallingly behaved (according to the introduction Ackerley became something of a social pariah for the 16 years he spent with Tulip) and Miss Canvey tells it like it is: “ ‘Tulip’s a good girl. I saw that at once. You’re the trouble.’”

As an aside, I had to say goodbye to my sweet wee boy this June, and the vets could not have been kinder, or more respectful and caring. They even relaxed their own lockdown rules so I could be with him when he died (still all very careful and socially distanced). This was the last picture I took of him, just before he became unwell:

So I’m very glad Ackerley and Tulip find Miss Canvey, but unfortunately her insight doesn’t result in any changes and Ackerley observes: “people seem to resent being challenged whenever they approach their own sitting or dining rooms.”

He does feel some sympathy for the local shop owners though (somewhat surprisingly, as he does come across as a terrible snob), when Tulip fouls their frontage:

“True they were horrid people, but no doubt they had their burdens like the rest of us, and Tulip’s gift would not help to uplift their hearts to a sweeter view of life.”

Ultimately what Ackerley captures in My Dog Tulip is the close bond that is unique to every human and animal relationship; and what us animal lovers know for sure, that they behave infinitely better than humans:

“But if you look like a wild beast you are expected to behave like one; and human beings, who tend to disregard the savagery of their own conduct, shake their heads over the Alsatian dog. ‘What can you expect of the wolf?’ they say.”

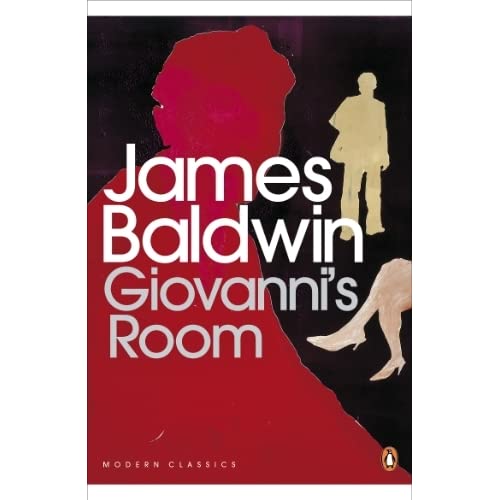

Secondly, Emma at Book Around the Corner suggested reading Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin and I am so glad she did. You can read Emma’s review here. This was my first James Baldwin and on the strength of this novella I’ll definitely be seeking out more of his work. He is a stunning writer: precise, poetic, insightful and so deeply moving. I knew from the opening lines, told from the point of view of young blond American David, that I’d found a writer to love:

“I stand at the window of this great house in the south of France as night falls, the night which is leading me towards the most terrible morning of my life. I have a drink in my hand, there is a bottle at my elbow. I watch my reflection in the darkening gleam of window pane.”

It’s a terrible morning because Giovanni, the man David loves, is going to be executed. They met in Paris in a gay bar where Giovanni was a barman, and quickly became lovers. Giovanni’s dilapidated lodgings provide the suffocating background to the most profound experience of David’s life:

“I scarcely know how to describe that room. It became, in a way, every room I had ever been in and every room I find myself in hereafter will remind me of Giovanni’s room. I did not really stay there very long – we met before spring began and I left there during the summer – but it still seems to me I spent a lifetime there.”

It is David’s self-hatred and wish to not be as he is that casts a shadow over their relationship. He longs for a fantasy life of heterosexual conformity:

“I wanted a woman to be for me a steady ground, like the earth itself, where I could always be renewed. It had been so once; it had almost been so once. I could make it so again, I could make it real.”

(David has a girlfriend, Hella, who is exploring Spain and deciding whether to accept his marriage proposal when he meets Giovanni.)This self-hatred means David is not always likeable but he is always believable. It makes him very judgemental towards how other gay men lead their lives, and he has horrible attitudes towards anyone he views as effeminate. His older friend Jacques picks him up on his behaviour, in an eloquent plea for humanity:

“There are so many ways of being despicable, it quite makes one’s head spin. But the way to be really despicable is to be contemptuous of other people’s pain. You ought to have some apprehension that the man you see before you was once even younger than you are now and arrived at his present wretchedness by imperceptible degrees.”

The story unfolds towards its inevitable tragedy that we know from the start is looming over the characters. It’s a heartwrenchingly sad tale that captures the deep and profound damage that can occur when the pain and frustration of a life unlived is inflicted on others.

I could have quoted so much from this novella. It is full of passages breathtaking in their beauty and wisdom. Effusively recommended.

“But people can’t, unhappily, invent their own mooring posts, their lovers and their friends, anymore than they can invent their parents. Life gives these and also takes them away and the great difficulty is to say Yes to life.”

To end, I’d normally pick a song from 1956 but none of them really took my fancy. So instead, a song for the year we’re in now. I’ve mentioned before that at times of trouble in my life there is one man I always turn to. That man is David Bowie. During the weirdness of 2020, he has not let me down. Yet also this year I’ve found myself seeking solace with another…

Bruce Springsteen has jokingly said that he writes the same song over and over. The song he’s referring to is about feeling powerless, trapped by circumstance, wanting to escape and still trying to reach out. That pretty much sums up the current situation doesn’t it?

I think so many of us are waiting on metaphorical sunny days. Here’s hoping they’re not too far away. At least I’ve managed to stop bursting into tears when he sings ‘everything’ll be ok’ which is a marginal improvement:

(Also at 4:25 Bruce does a knee slide, which contains the important message that you can be a 70 year old rock god but you’re never too old or too cool to launch yourself across a temptingly shiny floor like a giddy child…)