‘Tis the season of gluttony and excess, but how about some amuse-bouche in the form of festive short stories, before settling down with a chunkster tome to while away the long winter evenings?

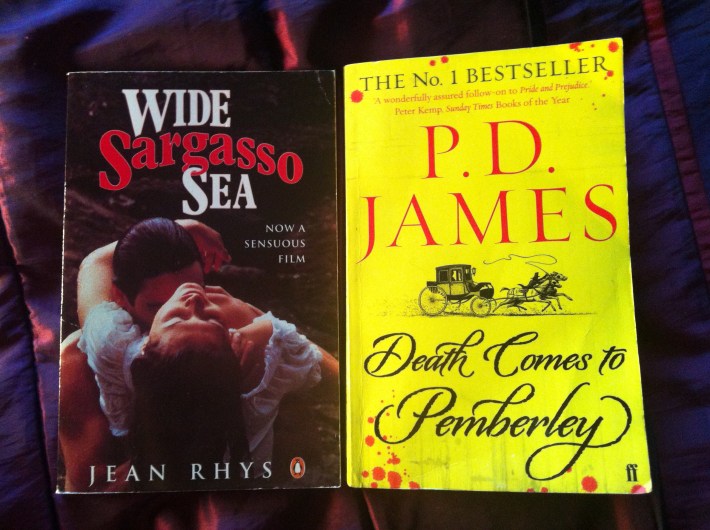

Festive Spirits by Kate Atkinson (2019) features three very short stories. It’s a small hardback which is sold in aid of Sightsavers.

Given their very concise length, I can’t say too much except they’re all as inventive and witty as you would expect from Atkinson.

In Lucy’s Day, a busy, exhausted mother attends her children’s nativity play.

“The Nativity was a dishevelled construct made mostly, as far as Lucy could tell, from lollipop sticks, cotton wool and hamster bedding. And lentils. The school used lentils a lot in its artwork, as well as pasta and beans. You could have made soup from some of the collages Beatrice and Maude brought home.”

In Festive Spirit, a woman reflects on her unhappy marriage to her successful husband and takes metaphysical steps in keeping with the time of year:

“When he was a boy he didn’t know anyone who got their hands dirty for a living. Now he was an MP everyone he knew had dirty hands.”

The final story, Small Mercies, returns to familiar domesticity and captures the sadness and loneliness experienced by so many at this time of year. But there is a glimmer of hope for middle-aged Gerald.

“It was difficult to make out his mother’s words, laced as they were with emotion and free alcohol.”

Festive Spirits is a quick but very worthwhile read. Kate Atkinson is great at short stories and these capture the time of year without sentimentality but also without any bitter irony. Highly enjoyable.

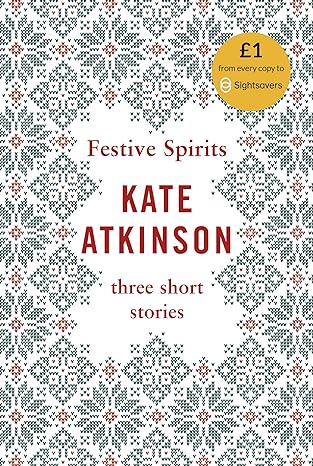

PD James’ collection Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales (2017) features two stories set at this time of year. The Murder of Santa Claus is the longest in the collection and probably the weakest (the denouement is someone explaining to the murderer how they know they did it) but still so much to enjoy.

It begins with Charles Mickledore, an author of cosy crimes, (“I’m no HRF Keating, no Dick Francis, not even a PD James.”) looking back on Christmas 1939 when he was 16. He goes to stay with a distant relative, Victor Mickledore, in a country house, with other guests who don’t know each other that well.

There’s a faithful secretary, an aging starlet, the couple Victor booted out of their home, and a dashing pilot. There are long-held resentments regarding Victor possibly killing someone in his car and paying off his valet as an alibi.

“The paper tore apart without a bang and a small of object fell out and rolled over the carpet. I bent down and picked it up. Wrapped neatly in an oblong of paper was a small metal charm in the shape of a skull attached to a key ring; I had seen similar ones in gift shops. I opened the paper folded round it and saw a verse hand printed in capitals.”

The verse is a death threat of course, which Victor disregards and insists the Christmas traditions will go ahead as usual, including his routine of dressing up as Santa and delivering presents. The title tells us all will not end well…

It’s hard to write a satisfying whodunit in a short story form and as I mentioned, this was a bit clunky. But PD James is such a brilliant crime writer it was still highly readable, and she clearly had a lot of fun with the cosy crime tropes and characters. The Christmas setting made for a real treat too.

The first story in the collection, The Yo-Yo, also features an older man looking back on his youth and remembering a murder. The difference here being there is no mystery, as he witnessed the event directly.

“I found the yo-yo the day before Christmas Eve, in the way one does come across these long-forgotten relics of the past, while I was tidying up some of the unexamined papers which clutter my elderly life. It was my seventy-third birthday and I suppose I was overtaken by a fit of momento mori.”

It was Christmas years earlier in 1936 when he was being driven from his boarding school to spend the festive period with his indifferent grandmother, that the story takes place.

James expertly paces the story to the climax of the murder, and then demonstrates the fallout with equal precision. A recurring theme through all six stories is of people getting away with murder (no Commander Dalgliesh here to find the culprits!) and whether justice occurs only within the law, despite it, or not at all.

“We walked back to the car together, almost companionably, as if nothing had happened, as if that third person was walking by our side.”

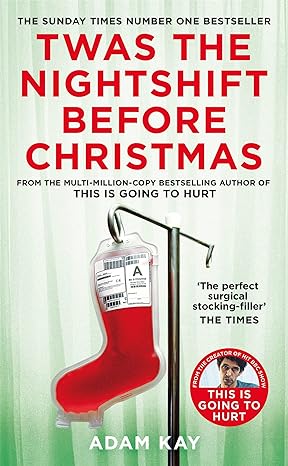

Finally, not short stories but an honourable mention to Adam Kay’s ‘Twas the Night Shift Before Christmas (2019) detailing his experiences working as a doctor over the Christmas period for several years. I haven’t read his hugely successful book This is Going to Hurt or watched the tv series with Ben Whishaw – having worked in the NHS for several years I find portrayals either inaccurate and infuriating or authentic and stress-inducing. I feared Kay’s would be the latter. But for some reason I was tempted by this little stocking filler, and he managed to take me right back, but entertain me rather than induce vicarious trauma. Highly recommended, as long as you don’t mind a lot of swearing 😀

“Sunday 26 December 2004

Full marks to the anaesthetist wearing a badge that says: ‘He sees you when you’re sleeping, he knows when you’re awake.’”

I really enjoyed my festive reads. Brona from This Reading Life has suggested we use the hashtag #ALiteraryChristmas for festive posts, so do join in if you’d like to!

To end, I’m never ahead of the game on anything, but this year I snapped up on pre-order the Christmas album by these two titans of contemporary folk music: