On Saturday I had a BIG birthday.

Why thank you, Mr DiCaprio. Yes, ‘twas the big 4-0 for me so this week I’m looking at one book written in 1977 and one book set in 1977. What they’ve taught me about the year of my birth is that much as nostalgia-fest programmes will try and convince me I was born into a glittery glam-rock utopia:

In fact I was born into a post-colonial nightmare of racism and corruption. 1977 was rubbish.

Firstly, the novel written in 1977, Petals of Blood by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, a damning indictment of the legacy of colonialism and political corruption. Set in Kenya not long after independence from the British in 1964, it is one more stop on my Around the World in 80 Books Reading Challenge, hosted by Hard Book Habit. It tells the story of Munira, a teacher; his friend Abdulla, a shopkeeper; Wanja, a barmaid and object of Munira’s affection; and Karega, a young man who wants to know about Munira’s history of school strikes and acts as the voice of communist ideals in the novel. All have moved to the remote village of Ilmorog to try and come to terms with the fallout from the Mau Mau war and build a life for themselves in the new republic. The title image recurs throughout the story. At its earliest point it is voiced by a child in Munira’s class:

“ ‘Look. A flower with petals of blood.’

It was a solitary red beanflower in a field dominated by white, blue and violet flowers. No matter how you looked at it, it gave you the impression of a flow of blood. Munira bent over it and with a trembling hand plucked it. It had probably been the light playing upon it, for now it was just a red flower.

‘There is no colour called blood. What you mean is that it is red.’ “

What emerges throughout the novel is that of course, there are literally petals of blood. Kenyans have fought and died on their land and their blood is in the earth. Stories of Munira’s school strikes show how indoctrination under empire was a mix of politics, religion and outright racism:

“We saluted the British flag every morning and every evening to the martial sound from the bugles and drums of our school band. Then we would all march in orderly military lines to the chapel to raise choral voices to the Maker: Wash me Redeemer, and I shall be whiter than snow. We would then pray for the continuation of the Empire that had defeated the satanic evil which had erupted in Europe to try the children of God.”

Following severe drought, the residents of Ilmorog travel to Nairobi to speak with their MP. They encounter indifference at best and outright hypocrisy and corruption at worst from businessmen, their MP, a reverend, which allows wa Thiong’o to explore what and who a new society is built on.

“And suddenly it was not her that he was looking at, seeing, but countless other faces in many other places all over the republic. You eat or you are eaten. You fatten on another, or you are fattened upon.”

If this sounds unremittingly bleak, the residents do also encounter a principled lawyer who helps them. If it sounds polemical and more of a treatise than a novel, it isn’t. wa Thiong’o is furious at the injustice and corruption he portrays, but the power of Petals of Blood is that it is never at the expense of believable characters. Munira, Abdulla, Wanja and Karega bring home the human cost of political decision-making and large-scale corruption.

“She had carried dreams in a broken vessel.”

Petals of Blood is an incredible novel. Angry and urgent, ultimately optimistic and with a belief that human beings can make better lives for themselves and for one another, but with a clear-sighted view of the damage we can wreak.

“It was really very beautiful. But at the end of the evening Karega felt very sad. It was like beholding a relic of beauty that had suddenly surfaced, or like listening to a solitary beautiful tune straying, for a time, from a dying world.”

Looking for the name of the translator of this novel, I was surprised to discover that wa Thiong’o wrote in the language of his country’s colonisers. Apparently Petals of Blood was the last time he did so, and he has since written in Gikuyu and Swahili. He has led a fascinating life, including time as a prisoner of conscience, which you can get a taste of on Wiki.

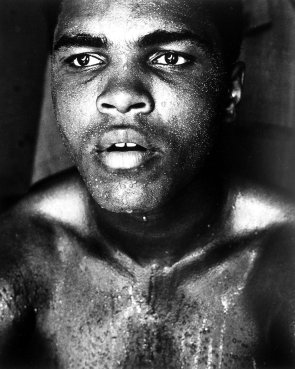

Image from here

Secondly, Jubilee by Shelley Harris (2011), set on the day of a street party to celebrate the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, and also in 2007, where a 30 year reunion of the people captured in a famous photo of that day is planned. The photo featured Satish, the son of Ugandan refugees fleeing Idi Amin, sat amidst his white neighbours:

“Here he was after all, an Asian boy happy in his white-majority Buckinghamshire village, and posing only a minimal threat to house prices.”

For reasons of his own, Satish has no desire to recreate that day. In 2007 he is married to a woman he loves, has two children and a successful career as a paediatric cardiologist. He also has an escalating addiction to diazepam. We know something awful happened to him on the day of the Jubilee, and by moving back and forth in time, Harris is able to show how the celebration built to crisis, and the fallout thirty years later. This is handled deftly, and didn’t get tiresome. Similarly, the period details are in abundance but not too heavily rammed home, possibly because the author is drawing on her lived experience as the daughter of 1970s immigrants to Britain, fleeing apartheid in South Africa.

“mushy peas; scampi; egg-and-bacon sandwiches; chips and mash and roasties – every iteration of the glorious potato; faggots; fry-ups; fish and chips; jelly and rice pudding; apple pie and Artic roll….He wondered what might happen if these were the only things he ate. Would it build up Britishness in him, all this English food? Would it drain his colour, sharpen his soccer skills, send him rushing into church?”

Satish encounters both casual ignorance and outright racist prejudice from his neighbours, and this is not shied away from but also not dwelt on, as young Satish does not dwell on these things. As adult readers, we know where the hatred can lead and its enduring effect on Satish, which lends the novel an underlying sense of menace.

“What were they exactly? Indian? Ugandan? He had never been clear. But this was neither their country nor their culture, and no matter how many Union Jacks they raised, they would always be waving someone else’s flag.”

Depressingly, these attitudes do not make the novel a period piece. There is a still need anti-racism marches, with Stand Up to Racism taking place this Saturday, on UN Anti-Racism Day.

Jubilee builds carefully towards its denouement, and shows the long-term damage that blind prejudice can inflict. It also shows how an act of hatred does not define either the perpetrator or the victim, and the power of forgiveness and reconciliation towards the events of our lives and the choices we make. I don’t know what it was about Jubilee that stopped me totally loving it, but it is a good read and effective evocation of a moment in time.

Image from here

To end, the cheesy earworm that was number one the week I was born. I’ve always thought my enduring love of sax solos came from Careless Whisper, but maybe this made an impact at a very impressionable age. All together now: ya-da-da-da-da….